You can thank action-movie madman Renny Harlin and his film about a horde of supersmart sharks for helping create Canada’s most respected and influential film magazine.

In the summer of 1999, Toronto film critic Mark Peranson was writing freelance reviews for NOW Magazine, assigned third-tier movies that the alt-weekly’s staff wouldn’t touch. But after Peranson gave Harlin’s knowingly absurd killer-shark thriller Deep Blue Sea the paper’s highest rating, his editor informed him that his criticism “wasn’t meeting readers’ demands,” and he lost his coveted gig covering the Toronto International Film Festival.

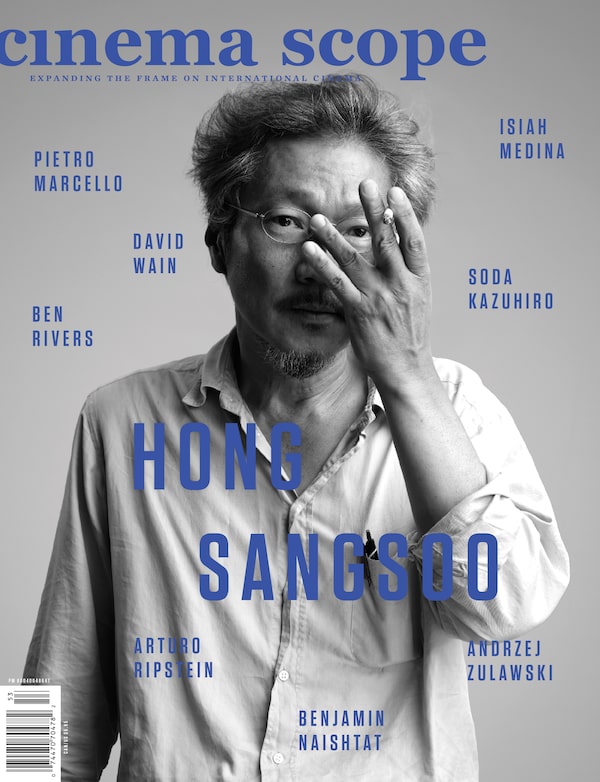

Cinema Scope started as a scrappy zine handed out to TIFF attendees on the street.Cinema Scope

“I thought, well, if they’re not going to want me, then I can do it myself,” Peranson recalls.

And so Cinema Scope was born. What started as a scrappy zine handed out to TIFF attendees on the street – never inside a theatre, a space strictly the domain of official festival sponsors – became not only Canada’s premiere home for sharp and fearless long-form criticism, but also an internationally renowned institution capable of launching a filmmaker’s career.

Yet after 25 years and persistent financial instability, the end credits have arrived. Last month, Cinema Scope published its 97th and final print edition, and effectively shut down its online operation (including its annual TIFF review package).

To mark the end of an era in film culture, The Globe and Mail presents an oral history of the most influential English-language film magazine of the past quarter-century.

Mark Peranson, editor and publisher: Somehow we got copies out during TIFF that first year, and decided to keep going. I borrowed money from my father, which I paid back eventually, but you can’t get government grants until you show that you’re serious about publishing. The only way this magazine could survive that first year was to do it without making any money.

Jason McBride, former managing editor: I vividly recall seeing the first issue when I was standing in line at the Uptown Theatre during TIFF. Mark was handing out copies with Tim Roth on the cover. At the time, there were some Canadian film magazines – Take One, POV, Montage – which were all okay in various ways. But Scope felt like a leap forward in terms of the writing and the kinds of films covered.

Guy Maddin, filmmaker (My Winnipeg): I started off as a really isolated filmmaker, which might have been a strength of mine. But I had no idea how far I was falling short of what contemporary filmmakers had been making until Cinema Scope enabled me to learn, one issue at a time, what the rest of the world was doing. I’ve made things which have been generously championed by Cinema Scope since, but it also allowed me to see what’s been charted by other filmmakers, so I could at least try.

After a few years, Peranson secured arts council funding, which fluctuated but never exceeded $20,000 annually. Meanwhile, the magazine’s reach expanded to crucial circles, both at home and abroad.

Peranson: The thing that gave it momentum was when James Quandt, founder of Cinematheque Ontario, programmed a “Best of the ‘90s” series in 2000, and we did a big issue on that theme. The film criticism community at that time in Toronto needed something to push it into a serious direction.

Adam Nayman, contributing editor: I remember going to that ‘90s Cinematheque series when I was a teenager and getting the second issue of Scope, which made you feel like, “Oh my god, my cinephilia is being ratified in real time.” And it’s being done by something printed within this city.

McBride: The more obscure a film was, the more Mark was interested. We would have gentle disagreements over what would be on the cover, and Mark would err on the side of obscurity. It was important to him that the magazine not seem provincial or parochial. Guy Maddin was on the same level as French director Bruno Dumont.

Even as Peranson became more immersed in global film-festival culture – securing programming jobs in Locarno, Switzerland, and then Berlin – Scope never lost sight of homegrown artists.

Denis Côté, filmmaker (All That She Wants): I had no real problems being slowly recognized internationally and in Quebec, but for us, Canada is a whole different ball game. Cinema Scope helped me echo my work after the usual two screenings during TIFF. It was the only serious and respectable cinephile magazine.

Nayman: Canadian filmmakers like Kaz Radwanski, Antoine Bourges, Ashley McKenzie, Matt Johnson, Sofia Bohdanowicz – no one wrote about them before Scope. Mark was very good about keeping an eye pointed at Canada and keeping tabs.

Atom Egoyan, filmmaker (The Sweet Hereafter): The period that Cinema Scope emerged was a period that I had resistance from a lot of the critical community. Which was why it was so gratifying to be featured in their last issue, for Seven Veils. But it was still important to me, and a blast to read. Mark’s editorials often made me laugh out loud, the way he got that vulnerable dance that film festivals have to do. It wasn’t beholden to any junkets. And see what it did for Pedro Costa, Hong Sang-soo, Albert Serra.

Filmmaker Atom Egoyan says Cinema Scope was important for shining a light on people like Pedro Costa, Hong Sang-soo and Albert Serra.Cinema Scope

Andrew Tracy, former managing editor: We didn’t really have the internet to lean on back then, so Scope offered a way to discover this whole other world of contemporary cinema.

By the mid-aughts, Scope’s name carried weight across the world, but nobody was getting rich off the endeavour. Nor was anyone even barely scraping by.

Nayman: People visiting Toronto would ask, “Can we see the Scope office?” Oh, you mean Andrew Tracy’s living room? The magazine’s network was wide but stretched thin in terms of resources. Mark was running a Canadian magazine from a suitcase in Europe for much of the time I was working there. And it couldn’t have happened without Andrew. Not just in him being a strong editor, but literally lugging boxes and physically mailing the thing.

Tracy: There was a lot of frustration, and eventually I just didn’t have enough time and effort to put into helping professionalize it. I tried to put a rational accounting model in place for a while, but the finances were very archaic.

Peranson: I’m a terrible publisher, and had no idea what I was doing. At some point, I could have turned it into a non-profit. I could’ve been more organized in terms of accounting.

But as Scope managed to keep publishing, its influence grew in tandem with the rise of online film criticism, and the magazine eventually set up a website (where every issue from No. 50 onward can now be found).

Erika Balsom, contributor and scholar: No one thinks that literature begins and ends with Harry Potter, but there are people who think that cinema begins and ends with the Oscar nominations, at best. So here was a role of advocacy of not just particular films, but the medium.

Nayman: The magazine’s name was like a secret handshake at film festivals. I was at the Locarno Film Festival with Mark not that long ago, and I met Toni Erdmann director Maren Ade, who I think is a genius and wouldn’t just strike up a conversation with. But I said I was from Toronto and wrote for Scope, and she was like, “Oh, of course!” Then there was finding out that people like Jim Jarmusch used to subscribe, or a filmmaker seemingly on their own planet like Paul Verhoeven read the magazine, and not only the pieces about him.

Tracy: A lot of the real path-breaking writing was done, if not personally by Mark, then at his instigation. A lot of people view Mark as breaking a filmmaker like Portuguese director Pedro Costa to North American audiences.

The magazine became not only Canada’s premiere home for sharp and fearless long-form criticism, but also an internationally renowned institution capable of launching a filmmaker’s career.Cinema Scope

Pedro Costa, filmmaker (In Vanda’s Room): In 2006 at Cannes, our film Colossal Youth was trashed by all the critics in the world. But then Mark wrote a wonderful piece, we had a long conversation, and Cinema Scope released a great cover. They never changed nor eased their support. It had an artisan energy: young writers rallying around a common effort.

C.W. Winter, filmmaker (The Works and Days of Tayoko Shiojiri in the Shiotani Basin): Given the difficulties of financing for non-blatantly commercial films, the leg up from Cinema Scope gave a number of filmmakers a lease on life – a better chance to be able to make another one. In some ways, it badgered other publications into having to cover these films. Or at least it provided a nudge.

Benny Safdie, filmmaker (Uncut Gems): Cinema Scope has always tried to hold movies and culture to such a high standard, while looking to connect ideas and push the whole form forward. It was something to pay attention to and find out new things from. I can speak from direct experience: Mark and Adam knew I was a fan of Nathan Fielder, a fellow Canadian, and they asked me to write an essay about anything I wanted regarding Nathan For You. I was so honoured, because to have a criticism article in such an amazing magazine meant a lot. And I’m sure this deep dive was an unknowing precursor to working together with Nathan on The Curse.

Sean Baker, filmmaker (The Florida Project): It was a career milestone for me when Adam interviewed me and wrote about my 2012 feature Starlet in issue 52. It was one of the first times I felt seen and recognized in the world cinema scene.

Yet the magazine could also be viewed as insular, and diverse only in the films it wrote about.

Andréa Picard, senior curator at TIFF: I will note that, for some time, I was frequently the only woman writing for the magazine – but this was also endemic of the film industry in general. (The magazine’s long-time designer was a woman, though.) The magazine evolved, taking stock of the field and its changes – holding steadfast to a vision that was completely unbeholden to the industry – and began introducing a younger generation of writers, including many talented women.

Nayman: It didn’t change fast enough in terms of representation and diversity of writers. And when an effort was made to reach out beyond the usual circle, there might have been some skepticism about how insular the contributor base was.

As influential as Scope was, though, the writing on the wall started to become increasingly hard to ignore.

Peranson: The past few years have been extremely busy for me. And 25 years without getting paid – it’s exhausting. I thought maybe we could go to 100 issues, but it didn’t work out.

Côté: We can say there’s no need to cry for the slow disappearance of paper magazines, but it had something comforting, serious, official. It was there to remind you that serious, hardcore cinephilia is a tool, or even a weapon, to succeed in the art-film world.

Egoyan: There’s a democratization of film criticism now, but in some ways, art forms consist of a curatorial admission process. As a visual artist, you’re waiting for a gallery or museum. For film, it was a festival, or being consecrated by an editorial. But taste is not how it seems to work in film culture at the moment.

Tracy: My hope is that if someone were to take it up, a good first stage would be to preserve the past, to centralize its 25-year history online. It’s just waiting on someone to help, either financially or with their time.

Peranson: I’m proud that I outlasted NOW Magazine. You can print that.

Barry Hertz

Barry Hertz