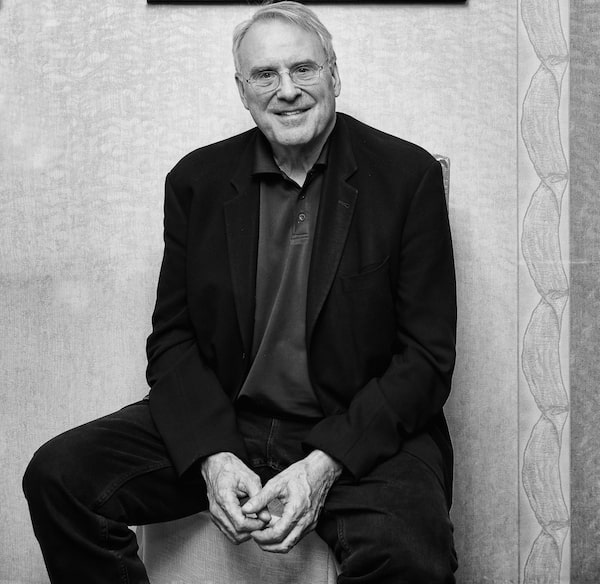

Former NHL player and author Ken Dryden has collaborated with Scotty Bowman on his seventh book, Scotty: A Hockey Life Like No Other.Handout

In 1983, Ken Dryden wrote a bit of a ballad, if not quite an ode, about a former coach of his.

“Scotty Bowman is not someone who is easy to like,” Dryden confided in The Game, the memoir he published after retiring from his NHL career, a book that’s still roundly recognized as the most insightful reflection on hockey ever written. “He is shy and not very friendly. … Abrupt, straightforward, without flair or charm, he seems cold and abrasive, sometimes obnoxious, controversial, but never colourful. … He is complex, confusing, misunderstood, unclear in every way but one. He is a brilliant coach, the best of his time.”

Together, as younger men in the employ of the then-mighty Montreal Canadiens, Dryden and Bowman reached hockey’s heights during the 1970s, when they coincided on five of the six Stanley Cups the team won in nine years. There were other key players you could name from the Canadiens’ decade of dominance, but none who played a more important role than the coach or his first-choice goaltender.

Both men departed Montreal in 1979, Dryden for retirement, Bowman to continue coaching in Buffalo, Pittsburgh and Detroit. Dryden’s post-playing career has included stints as a teacher, a TV commentator, president of the Toronto Maple Leafs, a federal MP and cabinet minister. By the time Bowman retired from the bench in 2002, he was hockey’s (in sports parlance) winningest coach, with more victories to his name, in the regular season and playoffs, than anyone else in NHL history. All told, he’s been involved in the winning of 14 Stanley Cups in his career – second only to Jean Béliveau’s 17.

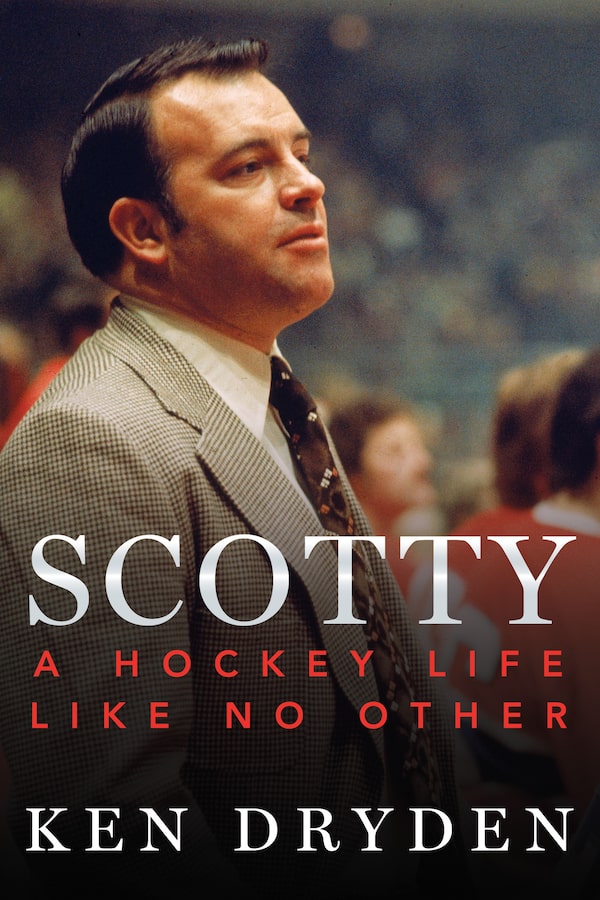

The most plentiful Cup years came in the seventies, when the coach and his goaltender helped propel Montreal to six championships in nine years. Now, 40 years later, Dryden and Bowman have collaborated on Dryden’s seventh book, Scotty: A Hockey Life Like No Other.

Handout

It’s a singular work in its own right – a biography, yes, but an unconventional one that also folds in a lively fantasy hockey playoff series. It’s a contrivance that allows Dryden to frame in the hockey history around Bowman by challenging him to choose the best eight NHL teams of all time and explore how it might go if they were to face off across time.

For Dryden, the relationship the men have shared since they first met at the Canadiens’ training camp in 1971 has remained consistent. “I think it’s essentially never changed,” he said in an interview. “I think we always got along. I think he sensed that I thought that he was absolutely the right guy to be the coach of our team and I think he felt sort of similarly about me. And we trusted each other.”

How the relationship expressed itself has, Dryden allows, been different at different times. In Montreal, in the seventies, “Scotty was somebody who was never comfortable with a conversation that lasted more than 30 seconds.” Later, in the eighties, working on his first book, Dryden sought Bowman out in Buffalo. “I thought we would be an hour or so – we talked for four hours.”

Dryden thought about writing about his former coach for a decade before he asked him in 2015 whether he’d be interested. He was. Two things that Dryden understood about Bowman: He has a prodigious memory, but he’s no storyteller. That’s where the historical fantasy came in: Dryden had to find a way of allowing the coach to look over the players on a roster, understand what each one could or couldn’t do – basically, find a way to let him coach.

So the two great hockey minds came up with a list of the teams they considered to be the greatest in NHL history, including the 1951-52 Detroit Red Wings and the 1983-84 Edmonton Oilers, along with their own 1976-77 Canadiens.

Armed with contemporary accounts and statistics, this was how they immersed themselves in the hockey past that Bowman had lived and helped to shape. The talking went on for a year, mostly over the phone, Dryden in Toronto, Bowman at home in Buffalo or in Florida, where he and his wife, Suella, spend their winters.

As the book makes clear, Bowman, who’s 86, is very much still in the game. Working as an adviser to the Chicago Blackhawks, the team his son, Stan, manages, he studies the NHL as attentively as he ever did, players and analytics, systems and tactics, what works, what doesn’t.

“The conversations were easy,” Dryden said. “I think they would have grown tired for both of us if it was just recollections. At a certain point, it’s not enough. It’s not interesting enough.” Bowman’s voluminous memory, Dryden realized, is more of a thriving depot than a dormant repository. “He remembers everything, but it comes to be in the service of whatever he's doing now and whatever he might be doing in the future.”

For the coach who’s never really quit coaching, memory isn’t about nostalgia. “It’s an exercise of having learned and of continuing to learn and of fitting even more pieces together to learn even more.”

I arranged to meet Dryden this fall near his home in midtown Toronto. Early to the rendezvous, I watched a passerby recognize and intercept him, shake his hand. At 72, the erstwhile goalie doesn’t look as if he’s lost any of his playing trim or the 6-foot-4 stature with which he made a career of fending off pucks, and it’s just possible to imagine him stepping in to relieve Carey Price in a crisis. In fact, the only time he has suited up in goaltending gear since he retired 40 years ago was in pads he borrowed from Price for a Bell Centre celebration of the team’s centennial in 2009. The incumbent Canadiens goaltender has otherwise superseded him: Dryden notes that both of his young goaltending grandsons wear Price’s number 31 on their sweaters rather than the famous, familial 29.

Don Cherry spent three decades broadcasting hockey’s blustering id. Through most of those same years, Dryden has approached the game more, shall we say, methodically and coherently. He has celebrated its variety and beauty; has attended it with a restless curiosity and public intellectual’s broadness of perspective and willingness to engage. In no one else’s biography do the adjectives “erudite” and “Conn Smythe Trophy-winning” coincide. He published The Game the same year he was ushered into the Hockey Hall of Fame. (Bowman joined him there in 1991.)

As Rick Salutin once pointed out, questioning and self-doubt come naturally to goaltenders, and in classrooms and lecture halls as well as on the pages of books and newspapers, Dryden has never stopped pondering the game’s finer points, riddling its riddles, questioning its verities, calling out its contradictions, trying to plumb – and, from time to time, restore – the game’s conscience.

In 2017’s Game Change, he fixed his focus on hockey’s response to the concussion crisis, positing a comprehensive plan to reimagine the culture of the game in order to eliminate hits to the head. Appealing directly to the man who has the power to lead the way, NHL commissioner Gary Bettman, Dryden was, as he has said, trying to create the conditions “by which he and hockey might make better decisions.”

Two years have passed since he personally presented a copy of the book to Bettman over lunch in New York. He’s still waiting for a response.

Scotty Bowman is seen with legendary Canadiens coach Toe Blake in 1963.Penguin Books

If in Scotty Dryden shifts from Game Change’s pointed advocacy, it’s no less passionate in its embrace of the game. With Bowman as his prompt and guide, he unpacks more than 70 years of hockey history, delving deeply into Bowman’s early years in Verdun, Que., exploring the legacies of his mentors in Montreal, legendary Canadiens coach Toe Blake and Sam Pollock, who is widely acknowledged as the greatest general manager in NHL history.

Growing up on the southern verge of the island of Montreal, Bowman was a fan of the Boston Bruins. He was a good player, not a great one. He was skating for the Junior Canadiens in 1952 when a rival defenceman swung his stick and fractured Bowman’s skull. He recovered and continued to play, but as he told Dryden, “I was no longer a prospect.”

He scouted, he coached junior hockey. When the St. Louis Blues joined the NHL for the 1967-68 season, Bowman was aboard as assistant coach and vice-manager. Promoted to coach, he managed, remarkably, to steer the Blues to three successive Stanley Cup finals in the first three years of their existence. That paved the way for his return to Montreal and the destiny awaiting him there: In 1971, he was hired as head coach of the Canadiens.

Setting aside the practical considerations of age and stage, Dryden has no doubt that Bowman would thrive as a coach in today’s NHL: “Because, again, he’s completely adaptable, and he keeps watching and puzzling and wondering.

“I make the point somewhere in the book: You don’t hear about a Bowman philosophy. There are philosophies of virtually every other highly successful coach. It’s the Wooten way, the Phil Jackson way, the Lombardi philosophy. You don’t hear that about Scotty Bowman.”

Call him aloof (many have), a manipulator (ditto), tyrant (look it up), Bowman was never anything other than results-oriented, a clinician, a wonk of hockey winning. The art he practised as a coach was one of adaptation and adjustment, of managing contingencies, making the most of the players he had on his roster, whether their pedigree was thoroughbred (Guy Lafleur, Dryden) or journeyman (Yvon Lambert, Pierre Bouchard).

“Philosophies just get in the way of what is,” Dryden said. “They stick you with a way of thinking that you may have come to for the right reasons – but then every next moment is another piece of life. You’ve got to see it for what it is. You cannot allow philosophies to get in the way.”

In October, when Scotty was published, Mike Babcock still had a job steering the Toronto Maple Leafs and Bill Peters was at the helm of the Calgary Flames. Coaching culture wasn’t under particular scrutiny the way it is two months later, or trending across social media, let alone roiling the NHL to its head office, if maybe not quite its very core.

Dryden doesn’t dismiss the discussion or play it down. He does keep his focus on his subject, his coach. Weighing his 1983 assessment of Bowman, he doesn’t dispute or regret it. Dryden recalls an essay he wrote in 2012 for Grantland in which he considered Bowman and his success alongside the brusque brilliance of Gregory House, the TV doctor that Hugh Laurie played for eight seasons, and Steve Jobs, the uncompromising and irascible Apple pioneer.

“Here are three people who are really high achievers in what it is they do. For the people around them, who worked with them, it wasn’t always an easy existence.

“And so what do they have in common? Why do people want to work with you? In every workplace, what you want most is to win. With Scotty Bowman, the question was: Do you want to win Stanley Cups or not?

“The difference between the three of them,” Dryden said, “is that Scotty wasn’t cruel. He was tough, he was demanding, but he wasn’t cruel.”

Playing for those superlative Canadiens in the championship years of 1970s wasn’t always easy, Dryden said. “All of us are geniuses in terms of our opinions. But genius isn’t opinion; genius is performance.” Bowman’s prime directive? “To understand performance, to enhance our performance, to get in the way of the other guys’ performance. It’s all about what is actually happening.

“He knew how good we were. He knew it was his job to keep reminding us of how good we were and to never allow us to get away with being less than what we were. And so whether he said something, didn’t say something, yelled or was silent, we knew what was going on in his mind.

"You couldn’t pretend that you were getting away with something less than what you were and what the team was. That was the part that made him really difficult to deal with. He was this kind of conscience … you might have your own conscience, but your conscience was crowded with his as well.”

So if Scotty Bowman found himself behind a bench in today’s NHL, how would he coach? “The way he’s always coached. Who have I got? Who’s the opponent? How do we find a way to win? If this doesn’t work, you try something else. The buzzer may go before you find an answer, but it isn’t that there wasn’t an answer. Next time we’ll find a different answer. And that will be an answer that’s only good enough for the first 10 minutes of that game, so I’m going to have to keep finding answers after that.”

Expand your mind and build your reading list with the Books newsletter. Sign up today.