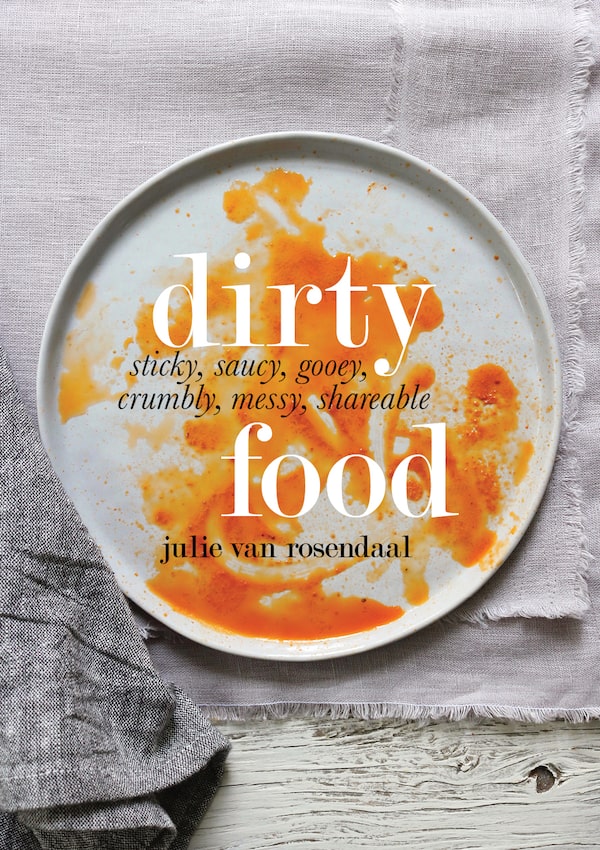

Julie van Rosendaal is self-publishing her new cookbook, Dirty Food.Jeremy Fokkens/Supplied

For as long as I can remember, cookbooks have been my thing. According to my mom, I learned to read by reading cookbooks, and have kept a rotating stack beside my bed ever since.

I was introduced to the idea of self-publishing early – growing up in Calgary, some of Canada’s most successful cookbook authors were our neighbours, and the parents of some of my school friends. The original Best of Bridge ladies had no experience in the industry, but knew how to feed their families (and their bridge club) well, and decided they’d figure it out as they go. The first Best of Bridge book came out in 1975; a bit further north, Jean Paré released the first Company’s Coming cookbook from her home in Vermilion, Alta., in 1981. Both self-published, each series has sold more than four million and 30 million copies, respectively.

Why we need a cookbook celebrating all things sticky, gooey and messy

Although few competing books were being released at the time, those numbers are astonishingly high, even compared with big-name celebrity chefs working with large publishing houses both back then and today. In fact, some of the country’s top-selling cookbooks have been self-published – in 1996, the uniquely pun-heavy Looneyspoons, by Janet and Greta Podleski (backed by The Wealthy Barber’s David Chilton), become one of the fastest-selling books in Canadian publishing history. (It spent 85 consecutive weeks on the national bestseller list and sold 850,000 copies.) More recently, Greta Podleski’s Yum and Yummer was the number one selling cookbook in Canada from the time it came out in the fall of 2017 until the fall of 2019, when major discount bookseller Costco removed it from its book offerings after an unusually long run.

Author Greta Podleski's Yum and Yummer was Canada's top-selling cookbook for two years.The Globe and Mail

Having had the concept instilled into my psyche early on, it was an easy decision to self-publish my first cookbook, One Smart Cookie, back in 1999. I’d heard at the time that publishers accepted as few as 1 per cent of book pitches anyway, so the traditional route seemed an unlikely option. Although I didn’t reach Bridge, Paré or Podleski numbers, I did sell 10,000 copies in the first year, generating enough interest from publishing companies to write 10 books with four publishers over the next 18 years.

For many writers, academics and creative types, publishing a physical book remains the gold standard. There is prestige in landing a book deal with a publisher, a (totally justified, author friends) sense of affirmation that one’s work is worthy of sharing on a large scale, and self-publishing has historically been seen as a last resort for those whose books were rejected. But since the internet came along and levelled the playing field, allowing anyone anywhere to digitally publish their thoughts and recipes in real time with no need to print, bind and distribute, doing it yourself doesn’t have the same stigma it once did.

Coil and cerlox binding are no longer distinguishing features, making it harder to tell which books are published by small, independent publishers and which are released by larger publishing houses. Yet when I told people I self-published my latest cookbook, many initial responses were to ask if it would be available in stores – a common assumption, even among some author friends, was that it would be an e-book, or limited to copies I hawked myself at farmers’ markets.

For those unfamiliar with how traditional book publishing works (don’t worry – there are many), here are the basics: An aspiring author submits a proposal to a publisher (through an agent or not), or vice versa – it’s becoming more common for publishers to approach potential authors, particularly those who come with their own audiences. (In the cookbook world, this coincided with the rise of celebrity chefdom, and continues with food bloggers and home cooks who have built up large followings on social media.) If it’s agreed that the proposed topic is a good and timely idea, the author usually fleshes out her or his outline before negotiating a contract.

Typically, the author then receives an advance on future royalties: $1,000 is not uncommon in the cookbook world, nor is $50,000 (although the latter is becoming more of a rarity, and $10,000 to $25,000 seems to be the average in Canada). This helps cover the cost of recipe testing and pays the bills while a significant number of work hours are dedicated to writing a manuscript. As the name implies, the advance is a prepayment of any royalties to be doled out once the book starts selling – typically 10 per cent of the book’s net (or retail) sales, though sometimes royalties are negotiated up to 12 per cent or 15 per cent, often after a certain number of copies are sold. The author generally covers the cost of photography and food styling, which can easily eat up most if not all of their advance. The publisher takes care of the editing, layout and design, printing, warehousing (storage) and distribution – that is, getting the books into stores. Sometimes they’ll spring for a promotional tour, although unless you’re a big name, having flights and hotels covered is no longer the norm.

Then there’s another, less common publishing model: publishing houses also known as hybrid publishers (and often referred to as “vanity publishers”), which charge authors up to $100,000 to produce a book, including photography, editing, printing, warehousing and distribution – all the things a traditional publisher would take on. (These books are indistinguishable from those produced by traditional publishing houses, which benefits both publisher and author in terms of consumer perception.) The author then typically receives royalties on book sales, but 10 per cent of sales isn’t much when you’ve paid close to the full retail price per unit to publish a book in the first place.

And of course there are other ways cookbooks get published: I recently received an e-mail from a large publisher in New York that uses proprietary technology to analyze data and identify unmet demand, then fills that need by producing books fast. The ask, presented as an opportunity: to produce a 75-recipe, single-subject cookbook in a four to five week turnaround for a flat $4,000 fee, no royalties. One of their selling points takes advantage of the hybrid publishing model: They emphasize there is no cost to authors, suggesting it’s the norm for authors to pay to have their books published. The whole industry can be very confusing.

Supplied

To self-publish is to take all of these tasks on yourself: the design, editing and printing, warehousing and distribution. By going back to self-publishing with my latest book, Dirty Food, not only did I take the photos myself (which I’ve done when working with publishers anyway), I hired a designer and editor, had the books printed at Friesen’s in Manitoba, then enlisted a distributor to take care of the latter two; bookstores don’t like to order a few books at a time from a small publisher – it’s easier and more cost-effective to order a number of titles from a larger catalogue and have them shipped together, and on my end, order fulfillment is time-consuming and shipping is expensive, and I only have so much space in my garage.

Regardless of size, it’s a tough industry for both authors and publishers. The retail market has changed completely with the rise of online shopping; between Amazon and Costco, consumers expect to pay significantly less than a book’s list price. A 40-per-cent discount off the retail price used to be a typical wholesale cost for retailers, with larger chains requiring 50 per cent; now, bigger retailers are demanding up to 65 per cent off in order to help cover marketing fees and accommodate the steep discounts shoppers have become accustomed to. In a crowded industry being squeezed by large retailers, the vast majority of cookbooks are printed and bound in China, which contributes to a long lead time – it’s not uncommon for authors to submit their manuscripts a year or more before their book’s release date.

Another factor unique to the publishing industry: Retailers can return any books that don’t sell. In the past, they typically had a year to return unsold stock – damaged or not – but now many large chains demand unlimited returns. So as an author, you could be thrilled to have sold a thousand books, only to have hundreds of them returned a year down the road, when they’re no longer new, and far less sellable. (Publishers typically buffer this by holding back a percentage of royalty payments for an extra six months or so based on anticipated returns.)

Unless you’re selling a ton of books, writing them is not a particularly lucrative endeavour. It’s one many take on to fulfill a dream, or to lend clout to the income-generating parts of their careers. For me, a self-employed food writer who has built relationships in the media and food industry over the years, self-publishing made sense as an extension of my business – another way of reaching my audience. Doing it all myself costs more upfront, but allows for creative autonomy; I can decide what topics to write about, have books printed here on the Prairies and release them in a more timely manner, which seems fitting in an era of instant information and fast-moving food trends. And while I also have the potential to make more money if the book actually sells well, having my cookbook in a stack on someone’s bedside table is priceless.

Expand your mind and build your reading list with the Books newsletter. Sign up today.