Shehabaldin Ahmed, 27, works for the Sudanese ride-sharing service Tirhal. He is also a supporter of the pro-democracy movement. Now, the country's new military rulers have blocked internet access to silence protesters. But they have also crippled Sudan's digital economy, such as the app Mr. Ahmed's livelihood depends on.Andreea Campeanu/The Globe and Mail

Back in the days when the internet still worked, 27-year-old Shehabaldin Ahmed supported his family with a job at an Uber-inspired car service – and sent videos to his friends to show them the enthusiasm of Sudan’s pro-democracy protests.

Now both are impossible. After massacring more than 100 protesters a month ago, Sudan’s military regime shut down the internet on every mobile phone in the country. There are no signs of it returning soon.

The shutdown has crippled Sudan’s once-booming digital economy, eliminating jobs that depend on mobile banking or other apps such as ride-hailing services. But it has achieved its goal: inflicting a severe blow to the protest movement that had challenged the military rulers.

“We feel silenced,” Mr. Ahmed says. “It makes me feel so sad. I can’t tell people what’s happening in our country. I have a big responsibility to my family and I can’t support them now. It’s very depressing.”

Mr. Ahmed says Sudan's digital blackout has left him and other pro-democracy supporters feeling silenced.Andreea Campeanu/The Globe and Mail

Three months after a military coup, Sudan is just the latest of dozens of countries that have shut down the internet for political reasons, sometimes for a few days but often for weeks or months at a time.

In Africa, the Middle East and Asia, a growing number of autocratic governments are depriving their citizens of access to social media and other internet sites.

Last year, according to the digital-rights group Access Now, there were almost 200 digital blackouts in 25 countries, including India, Yemen, Iraq, Russia, Cameroon, Nigeria, Mali, Togo, Algeria and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Over the past month in Africa alone, internet shutdowns have been imposed in Sudan, Ethiopia, Mauritania and Chad.

By ordering providers to halt their mobile services, these edicts have made it increasingly difficult for protest movements to communicate.

In most cases, the shutdowns were imposed during an election or a political crisis. Governments have sought to maintain their grip on power by muting their critics and disrupting their ability to organize.

In Sudan, the regime has said very little about the reasons for the internet blackout, except to say it is necessary for “national security.” (Some hotels and large offices have avoided the shutdown because they have fixed internet lines, but the vast majority of Sudanese have no access to those lines.)

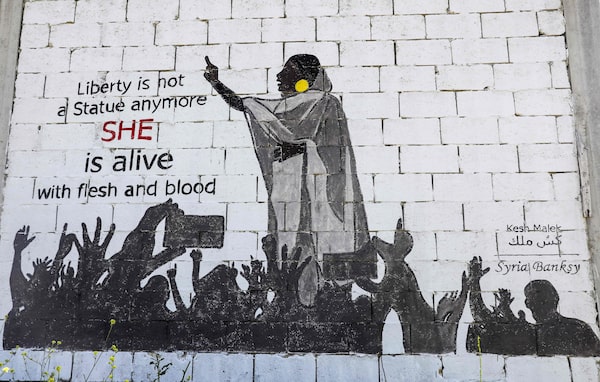

Kafranbel, Syria, April 12: A mural on the side of a farmhouse pays tribute to Alaa Salah, a Sudanese woman made famous by a viral video from a protest against then-Sudanese president Omar al-Bashir. In the early days of the Sudanese uprising, as in the Arab Spring revolts of 2010 to 2012, social media played a vital role in mobilizing people.OMAR HAJ KADOUR/AFP/Getty Images

Garawee town, June 15: A Sudanese man takes a selfie with members of the Rapid Support Forces, a paramilitary group enforcing the rule of the military council. Three months after that council took over, Sudan is one of several nations in Africa to limit access to the internet, mobile services and social media.STR/The Associated Press

The shutdown seemed to target protest leaders such as the Sudanese Professionals Association, which organized rallies with the help of a Facebook page that had more than 800,000 followers. The organizers have also routinely used Twitter to spread their messages.

Human-rights groups and the United Nations human-rights chief have denounced the shutdown. Some have warned that it is a potential threat to the lives of the Sudanese people, as it jeopardizes emergency communications and health information.

Mr. Ahmed, a rank-and-file member of the pro-democracy protests, still has scars on his foot from being hit by a tear-gas canister in April. Back then, he was able to post videos on Twitter showing the violent attempts to crush the protests. Now the military rulers have prevented that. “They closed the internet to hide their killing and raping,” he tells The Globe and Mail in an interview. “It hurts that they’re getting away with it. It hurts that I can’t tell people what’s happening here.”

It also hurts his income. After leaving university and struggling to find a job, he began working at a ride-hailing company called Tirhal, a Sudanese version of Uber. The service became so popular that he was able to earn more than $400 a month – enough to support his ailing mother and grandfather.

Today he still has the app on his phone, but it says: “No internet connection.” His income has vanished, and he is forced to borrow money from friends and relatives to survive.

To find news about the pro-democracy protests in a country where the official media are state-controlled, he has to make phone calls or send text messages to friends – both of which are relatively expensive. But he vows to keep supporting the protests against the military regime. “We have no other choice,” he says.

Ahmed Mohamed Ibrahim, another Tirhal driver, says the internet outage has destroyed his income.Andreea Campeanu/The Globe and Mail

Another Tirhal driver, 30-year-old Ahmed Mohamed Ibrahim, says he has lost all his income since the shutdown began. “My life has literally stopped,” he says. “It can’t get any worse than this.”

He has joined the street protests, but he has to interrupt his activism to check on his parents, using expensive phone credit or driving home to see them because he can’t use the free WhatsApp service to contact them. “It has been very stressful,” he tells The Globe. “But this is why we’re on the streets. We want to make changes because the government doesn’t care about us.”

One Sudanese lawyer launched a court case against a leading mobile service provider last month to challenge the internet ban. He won his case – but only his personal connection was restored. The rest of the country continued without internet.

Despite the blackout, the protesters have managed to keep their movement alive, holding small marches and meetings in neighbourhoods at night to spread their message with megaphones and leaflets, culminating in a massive protest by hundreds of thousands of people last Sunday.

But the internet disruption has devastated the digital economy. “It feels like we’ve gone back to the Stone Age,” says Osama Elbushra, a 23-year-old business student.

He works as an accountant at an export-import company that used a mobile-banking app and WhatsApp messages to buy crops from market traders across Sudan. But without internet access, its payments have become difficult and time-consuming, with agents having to rent cars and deliver cheques to the market traders. His company has reduced its staff, cut salaries and slashed their working hours.

An employee at a Khartoum travel agency waits at the computer screen.YASUYOSHI CHIBA/AFP/Getty Images

According to an internet shutdown cost calculator developed by two independent research groups, the disruption has cost Sudan’s economy about US$1.3-billion so far.

It has also created obstacles for United Nations organizations in a country where an estimated 5.5 million people are in need of humanitarian assistance.

“If you’re not in an office that has internet, there’s no more communication as soon as you’re out the door,” said Stephane Pichette, a Canadian who serves as the field operations chief in the Sudan office of Unicef.

“It’s taking us back in time. You can’t react quickly to events. When you’re in the field at a nutrition centre, for example, and you need to know when the last supplies were sent, you can’t get the Excel spreadsheet. You have to do everything by voice.”

But the agency has found creative solutions, and Unicef has still managed to provide measles and polio vaccinations to about 10 million children in Sudan in recent weeks, he said.

Our Morning Update and Evening Update newsletters are written by Globe editors, giving you a concise summary of the day’s most important headlines. Sign up today.

Geoffrey York

Geoffrey York