Boulder, Colo., 2018: Irma Carrillo holds up a hand-drawn picture of her heart with two holes in it, representing her two children, who have been missing since 1999. She is speaking at a hearing of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, where advocacy groups have been pressing for access to an FBI DNA database to help identify the bodies of people found along the U.S.-Mexico border.David Zalubowski/The Associated Press

Irma Carrillo’s two older children set out to walk across the desert from Mexico into Arizona in June, 1999, with a group of other would-be migrants and a coyote – a human smuggler. Yadira and Julio hoped to cross undocumented into the United States to earn some money, fast, to help out their mother; their father had just died, and she was swamped with medical bills. Not long after they crossed the border near the Rio Colorado, Yadira, 27, fell and broke her ankle; Julio, 24, stayed behind with her while the group went on.

Days later, another migrant from the group called Ms. Carrillo to give her the news that her children had not come out of the desert. She and other relatives began to search, contacting the Mexican consulate, the police – anyone they could think of. But the two were never found.

In 2016, Ms. Carrillo heard about the Missing Migrant Project of an NGO called Colibri, in Arizona, which aims to help people find their loved ones. She gave them a DNA sample, knowing there were hundreds of unidentified bodies – presumed to be those of undocumented border crossers who died in the attempt – stored on the U.S. side of the frontier.

But Ms. Carrillo’s sample has never been cross-checked against DNA from any of those bodies. Neither have any of the other 4,500 samples collected by Colibri and other organizations that together form the Forensic Border Coalition – academics, scientists, anthropologists and community groups who work together to identify the remains of migrants. The procedure, checking one set of samples against another, is not particularly scientifically complicated. But it hasn’t happened – despite six years of requests. The problems are ostensibly bureaucratic, but the activists involved believe the politically fraught nature of immigration and undocumented border crossing is what really lies behind the delay. In recent weeks, U.S. President Donald Trump issued a renewed series of threats to Mexico, warning he would impede some trade and legal border-crossing if Mexico did not do more to stop Central American migrants headed to the border.

The coalition has been pushing to make this happen for so long that, last October, it took the U.S. government before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, where an FBI lawyer tried to explain why her agency won’t attempt to match the DNA. The commissioners – moved to tears by testimony from Ms. Carrillo and others – told the U.S. delegation that it was incumbent upon them, under commitments made in international conventions, to figure out a way to make it work – and fast. But six months later, the FBI has done nothing to broaden the process.

“Sitting in that room, I felt like they don’t give value to the people or their pain or the disappearance,” Ms. Carrillo said in an interview. “They think of them as just two more people who were coming to America to commit crimes … I’m old, I have so many illnesses, I’m not sure how much time I have left – and I’m just waiting for an answer about what happened to my children.”

In Arizona's Pima County, a backpack lies in the Sonoran Desert in 2018. Dehydration and exposure are deadly risks for those attempting the desert crossing into the United States.LUCY NICHOLSON/Reuters

In Tucson, Ariz., forensic anthropologist Jennifer Vollner reviews the bones of a 16- to 20-year-old migrant from Mexico or Central America who died in the Sonoran Desert.LUCY NICHOLSON/Reuters

CANADA

Hundreds die in the attempt each year,

some on the U.S. side. If they can't be

identified through other means, their DNA

is collected for an FBI database. But that

rarely produces identifications, because

the migrant's family isn't in the U.S.

Detail

U.S.

MEXICO

Migrants from

Mexico and

Central America

travel north to

attempt to cross

the southern

U.S. border.

HONDURAS

GUATEMALA

EL SALVADOR

Families of missing migrants give DNA

samples to NGOs south of the border

that try to trace their loved ones -

but the FBI won't allow those samples

to be compared with the U.S. database.

ARIZONA

Here is an example

of the migrant deaths

that occurred near

the border in southern

Arizona from 1999 - 2018.

MEXICO

TRISH McALASTER / THE GLOBE AND MAIL

SOURCE: HUMANEBORDERS.ORG

CANADA

Hundreds die in the attempt each year,

some on the U.S. side. If they can't be

identified through other means, their DNA

is collected for an FBI database. But that

rarely produces identifications, because

the migrant's family isn't in the U.S.

Detail

U.S.

MEXICO

Migrants from

Mexico and

Central America

travel north to

attempt to cross

the southern

U.S. border.

HONDURAS

GUATEMALA

EL SALVADOR

Families of missing migrants give DNA

samples to NGOs south of the border

that try to trace their loved ones -

but the FBI won't allow those samples

to be compared with the U.S. database.

ARIZONA

Here is an example

of the migrant deaths

that occurred near

the border in southern

Arizona from 1999 - 2018.

MEXICO

TRISH McALASTER / THE GLOBE AND MAIL

SOURCE: HUMANEBORDERS.ORG

CANADA

Hundreds die in the attempt each year,

some on the U.S. side. If they can't be

identified through other means, their DNA

is collected for an FBI database. But that

rarely produces identifications, because

the migrant's family isn't in the U.S.

Detail

Families of missing migrants

give DNA samples to NGOs

south of the border that try

to trace their loved ones -

but the FBI won't allow those

samples to be compared with

the U.S. database.

U.S.

MEXICO

Migrants from

Mexico and

Central America

travel north to

attempt to cross

the southern

U.S. border.

HONDURAS

GUATEMALA

EL SALVADOR

ARIZONA

Here is an example

of the migrant deaths

that occurred near

the border in

southern Arizona

from 1999 - 2018.

MEXICO

TRISH McALASTER / THE GLOBE AND MAIL

SOURCE: HUMANEBORDERS.ORG

It’s impossible to know how many migrants die attempting to cross the border because coyotes don’t report the people they lose; some families are afraid to make missing person’s reports; and most of those who do make the reports in other countries (El Salvador, Honduras, Mexico), not the U.S. Mexico’s National Commission on Human Rights says a known 2,800 Mexicans have died in the crossing in the past decade, while the U.S. Customs and Border Protection agency says it found the remains of 7,505 people along the border between 1998 and 2018.

Every unidentified body found by U.S. officials is sent to a medical examiner, and if it is not possible to make an identification in other ways (from photos, tattoos, dental records or documents the person was carrying), a DNA sample is preserved. This is where the problem arises: The DNA in the U.S. goes into a national missing persons data bank, but these samples rarely match samples already in the data bank because the migrants’ families are in other countries. Even when a dead migrant does have a relative in the U.S. who could provide a sample, they may not know of the option or may be wary of U.S. law enforcement because they, too, are undocumented migrants.

“The U.S. is investing all this money to process the DNA of the unidentified remains of people, but they have very few hits because they have nothing to hit with – undocumented migrants typically don’t want to give even names to enforcement agencies to make a missing persons report, they don’t want to go to a U.S. law enforcement agency to give a sample," said Mercedes Doretti, a forensic anthropologist who represented the Forensic Border Coalition at the hearing. “But the genetic information we have collected, if it were compared against genetic information from unidentified remains found on U.S. soil, would almost certainly produce a very large number of identifications. And it would end years of searching, uncertainty and excruciating pain for hundreds of families. The fact that they won’t do it – it’s not a technical issue, there’s nothing here that we can change, that we can do to improve the way we collect samples – it’s a political thing.”

In response to questions from The Globe and Mail about how it intends to respond to the directive from the Inter-American Commission, the FBI said in an e-mailed statement, “The FBI is continuing to work with stakeholders and remains committed to addressing this important issue,” and that in addition to participating in working groups on the identification of missing migrants, the agency "has also been pursuing ways within the confines of the Federal DNA Act to assist in efforts to identify missing migrants.”

At the hearing, FBI lawyer Paula Wolff testified that federal law prohibits anyone other than law enforcement from having access to its Combined DNA Index System (CODIS) and that DNA matches can only be released to criminal justice organizations, not to groups such as the coalition. She said samples would have to be collected by a U.S. law enforcement officer to be considered legitimate for uploading to the FBI database. But Ms. Wolff appeared moved by the testimonies of Ms. Carrillo and the other parents. “As a mother and a representative of the FBI, I cannot agree with you more," she said. “I don’t think we have any disagreement regarding the what must be done – the only issue is working through the how it is to be accomplished.”

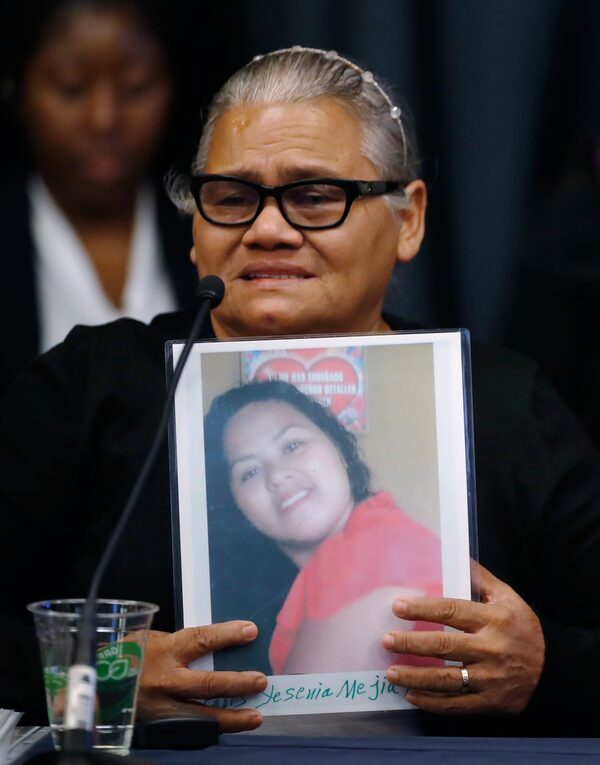

At the 2018 hearing of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, Jesus Reyes Leal of Honduras holds a photograph of her daughter, Yesenia Reyes. She has been missing since 2015, when she tried to cross the border into the United States.David Zalubowski/The Associated Press

Roxanna Altholz, a director of the International Human Rights Law Clinic at the University of California, Berkeley, who testified for the Forensic Border Coalition, said she left the hearing optimistic that Ms. Wolff and her colleagues were convinced there was no legal barrier, only a policy one. But the subsequent six months, in which no progress has been made, have left her questioning whether there is actually any will on the part of government to solve this problem.

The commissioners heard testimony about what is actually possible: Bruce Anderson, the forensic anthropologist for the Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner in Arizona, explained that his office has identified 364 of the 2,000 migrants who have been identified in southern Arizona by the end of 2018 – but only 47 of those were found in CODIS, the rest through matches with samples collected by the coalition. Starting in 2003, Prof. Anderson began to send samples to Bode Technology, a private forensics company in Virginia with a good reputation for getting samples out of old, dry bone. Today, Bode has a database of more than 1,200 unidentified profiles – almost all of which are migrants, Prof. Anderson believes. Ms. Doretti and her colleagues also send samples to Bode when they believe there is a high likelihood of a match (it can cost more than US$4,000 to compare a sample).

“The government has a point that anyone dead in the U.S. should go into CODIS ," Prof. Anderson said. "But if this is a Guatemalan woman who has never been here before, she’s not going to be in CODIS. And if the family doesn’t speak Spanish [about half the migrants coming out of Guatemala speak only indigenous languages] and doesn’t know where to turn – if the [NGOs] finally reach out to the family – that’s how to get an ID. You could scale this up.”

However, another forensic specialist says the Forensic Border Coalition and its supporters are not being practical or realistic with their proposal for a large-scale cross-check of samples.

Bruce Budowle is a professor of microbiology at the University of North Texas and an expert in using forensic science for identification. He heads a lab that receives about 80 per cent of the unidentified human remains in the United States each year, funded with millions of dollars in grants from the federal government.

He says the U.S. needs a system that allows for the long-term comparison of samples, and he isn’t convinced that having one or more NGOs contributing the family samples is sustainable. “It’s not the best long-term solution – government agencies have more money,” he said.

He is also dubious about the quality of the evidence the NGOs might provide. “Just because someone says they do DNA typing doesn’t mean they do it right – we want to make sure the labs are valid and reliable."

Ms. Doretti, a co-founder of the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team, counters that her agency collects samples following all the legal requirements for each country in which they work, that every donor gives informed consent and that samples are processed at a U.S.-accredited laboratory that is frequently used by the U.S. government.

Prof. Altholz said she sometimes has the sense that the FBI, and its supporters such as Dr. Budowle, don’t understand who they’re dealing with on this issue – that they do not realize that Ms. Doretti is one of the world’s foremost experts on criminal forensic anthropology, that her group is routinely called upon as expert witnesses by international criminal tribunals and asked by governments to help with sensitive cases.

“Is it because they have the word ‘Argentine’ in their name? I don’t understand it,” she said. “They could be a trusted counterpart with technical knowledge and legitimacy and credibility ... There are so many problems in this world that have so many complicated solutions. This is a very accessible, resolvable problem where the solution could bring a measure of peace to potentially thousands of people.”

Bea Abbott, centre, joins other attendees at the 2018 hearing in Boulder, Colo., in holding up photographs of missing people.David Zalubowski/The Associated Press