The end of Ukraine – the part still controlled by the government – is marked by a maze of chain-link fences and red-and-white-striped cement blocks, followed by a deep dirt trench that recalls Europe’s wars of the last century. Somewhere in the dark night ahead is a rival Russian line of defences and, beyond that, Crimea, the peninsula that Moscow seized and annexed five years ago next month.

It’s rare for a foreigner to appear at the Ukrainian military’s ramshackle final checkpoint. So much so that – even though I’m carrying permission papers from both the central government in Kiev and the migration office in the nearby city of Kherson – I’m escorted into a metal shack near the de facto border and quizzed by military-intelligence agents.

Why, they want to know, would someone with a Canadian passport want to walk into Crimea?

The answer is that I had been there, in Crimea, five years earlier. I had watched as masked Russian troops took control of the peninsula before staging a sham referendum used to justify Vladimir Putin’s decision to append the territory to Russia. Now, I wanted to see what had changed, to travel throughout the peninsula and speak to a cross-section of Crimeans about all that had happened since.

Listen to an audio version of this story:

Under Ukrainian law, the only legal way of doing so in 2019 is to journey overland, with the government’s written permission. After an hour of questions, the soldiers let me continue my frigid trek across the front line of a conflict that has reshaped the borders of Ukraine, and drawn a thick new line between Russia and the West. It’s roughly a kilometre on foot from the last Ukrainian fortifications to the first Russian position, but the journey is much greater than that.

Behind me – as my wheeled bag bounces along the muddy, potholed road that was once the well-travelled route between Kherson and the Crimean capital of Simferopol – lies a country that has launched two pro-Western revolutions over the past 15 years, and where the political consensus favours breaking centuries-old links with Russia in exchange for the hope of a new future in Europe.

Ahead of me is Russia’s first territorial acquisition since Josef Stalin seized vast swaths of Eastern Europe after the Second World War.

Mr. Putin’s brazen decision to annex Crimea plunged the world into a second cold war, a global conflict that has seen Russia and the West butting heads over the fates of countries as distant as Syria and Venezuela (with Moscow supporting the authoritarian regimes in both, as it did Viktor Yanukovych in pre-2014 Ukraine).

Russia also stands accused of meddling to help secure the 2016 election of U.S. President Donald Trump, a charge that may soon be formalized by special counsel Robert Mueller.

Relations hit another new low this month when both sides announced their intention to withdraw from a Cold War treaty that prohibits the possession and development of medium-range nuclear weapons. But Crimea remains the casus belli.

Canada, the United States and the European Union say they won’t lift sanctions they imposed, in the wake of the annexation, until Russia leaves the peninsula. And Mr. Putin – who wants the world to recognize Crimea as part of Russia, now and forever – won’t end his hybrid war as long as the West is deploying its economic arsenal against his country.

The three million Crimeans, meanwhile, are rarely considered. They’ve been reduced to pawns and victims.

I arrive at the Russian front line, marked by a newly built 60-kilometre fence topped with barbed wire and sensors, ready for more questions.

A guard, sporting a black fur cap, and a Kalashnikov rifle over his shoulder, seems as startled as his Ukrainian counterpart to see a foreigner on a Monday night. He tells me I’ll have to wait until his commanding officer arrives.

I brace for another ordeal. But the officer, when he appears, simply looks at my Russian visa and media accreditation, slaps a red stamp into my passport and wishes me a good trip.

As I walk through what feels like a long tunnel, framed by more steep fencing, I get my first glimpse of life in Mr. Putin’s Crimea. I look down at my British mobile phone, intending to tell my editors that I’ve made it across the frontier – but the device reads “No service.”

After a two-hour night drive south from what Russia calls its border, I wake up Tuesday in the Crimean capital’s Hotel Ukraina, the Soviet-era hotel I had used as a base while covering the world-changing events of 2014.

On the morning of the sham referendum, which came only weeks after Mr. Yanukovych’s ouster, I had walked to a nearby college being that was used as a polling station. There was genuine excitement in the city that day about the prospect of joining Russia, which many of the Crimeans I spoke with said was a more prosperous and stable place than revolution-seized Ukraine.

But there was also deep anxiety.

I watched as Simferopol residents lined up to drop their ballots into clear plastic boxes. Ostensibly meant to encourage transparency, the boxes also meant that others could see how someone had voted. Of the dozens of completed ballots I could read, not a single one spurned union with Russia.

There is an historic reason for Crimea’s attachment to Russia. The peninsula had been ruled from Moscow from the late 1700s until 1954, when Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev – in a bureaucratic shuffle – transferred it from Soviet Russia to Soviet Ukraine. But Crimea, unlike most of the rest of Ukraine, remained a place where the Russian language and the Russian Orthodox Church still ruled.

In 1991, Crimeans voted along with the rest of Ukraine to declare independence from the dissolving Soviet Union. But they did so grudgingly: Only 54 per cent backed the move in Crimea; nationwide, 90 per cent did so. In the decades that followed, Crimea stayed a land apart, consistently voting for pro-Moscow candidates such as Mr. Yanukovych.

When Mr. Yanukovych was ousted in February of 2014, Mr. Putin responded by sending special-forces troops to seize this fist-shaped land that punches south from Ukraine into the waters of the Black Sea.

Moscow portrayed the uprising in Kiev as a Western-sponsored and anti-Russian coup. Critically, that point of view was transmitted to Crimeans, most of whom relied on Kremlin-run TV channels for their information.

The full truth is awkward for both sides: Most Crimeans did, and do, favour union with Russia. But Crimea’s 2014 referendum, carried out under de facto military occupation, was both illegal under Ukrainian law and anything but free and fair.

Parked that morning five years ago, perhaps 100 metres from the voting station, was a green armoured personnel carrier staffed by balaclava-clad soldiers (who were then still pretending they weren’t the Russian army).

As I approached to take a picture with my phone, one of them shouted: “Photographs are forbidden!”

“Who says?” I asked, in Russian, before adding, “Who are you?”

The soldier stepped off the vehicle and slid his automatic rifle off his shoulder. “Who are you?” he snarled.

I raised my hands and backed away.

Defence lawyer Sergey Legostov is worried about how the law is being used to crush dissent in Crimea under Russian rule.The Globe and Mail

Five years later, a life-sized statue of a girl and her cat looking admiringly up at one of the “little green men” –the nickname Russian media gave the special-forces troops who oversaw the annexation, under the pretense of their being a local militia – stands outside the parliament building in Simferopol. Meant as a celebration of Crimea’s “reunification” with Russia, the statue can also be seen as a tribute to the Kremlin’s willingness and ability to trample the law when it chooses.

When I meet him near the start of my week-long trip around the peninsula, Sergey Legostov, one of Crimea’s most prominent defence lawyers, says the biggest change he’s seen over the past five years has been the utter disappearance of fair trials. In Ukrainian times, Mr. Legostov says he had a slightly better than 50-per-cent chance of getting a client acquitted, or at least having the sentence reduced to a fine or house arrest. Under Russian rule, he can think of just two cases in all of 2018 where the judge ruled in favour of the defence.

More worrying, he says, is the way the law is used to quash dissent. One of Mr. Legostov’s clients is Vladimir Dutko, a 53-year-old retired sailor who served in the Ukrainian navy before 2014. Mr. Dutko stands accused of plotting with two other former soldiers to sabotage strategic sites around the peninsula in a violent show of opposition to Russian rule. Mr. Legostov says the evidence against his client amounts to a cellphone – containing messages outlining the supposed plot – that Mr. Legostov says was planted at Mr. Dutko’s home by the very police who came to arrest him in November, 2016.

Mr. Dutko’s son Ilya says his father was chosen at random. “They want to show other [former Ukrainian soldiers] that they need to stay quiet if they want to live here,” 30-year-old Ilya tells me, anger flashing in his brown eyes.

Ilya Dubko tells the story of his father's arrest in Sevastopol.The Globe and Mail

That kind of warning, of course, cannot help but be noticed by citizens across Crimea, which under Ukrainian rule had gotten used to speaking freely, and occasionally standing up to the government. It’s clear that won’t be tolerated any more.

“Intuitively, you feel the pressure,” Mr. Legostov says. “You become more closed in whatever you’re doing – even if you’re with your family, or driving in your car.” He sighs when he recalls how excited Crimeans were in the spring of 2014. “We just had no idea what life in Russia meant.”

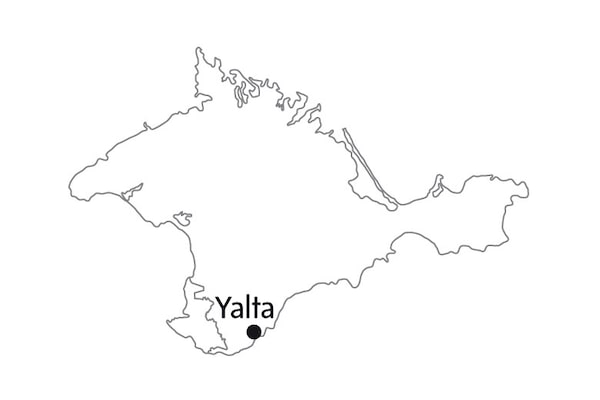

It was to better understand such changes that I had plotted my journey around the peninsula that Mr. Putin had captured, turning it, for the rest of the world, into something of a no-man’s land. From Simferopol, I would travel south, stopping in two cities I had visited in 2014: the laid-back valley town of Bakhchysarai, and then, 90 minutes farther southwest, the muscular Russian naval hub of Sevastopol.

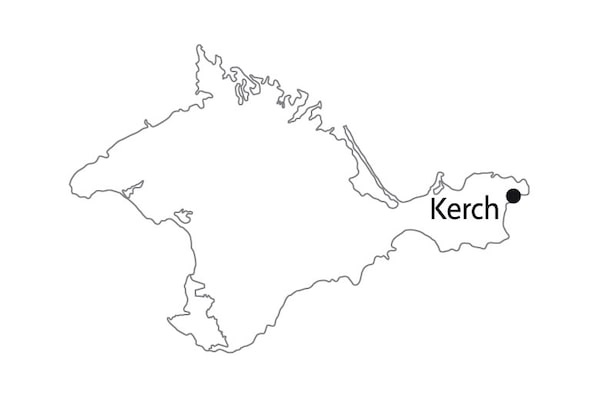

Afterward, I would follow the road that swerves between the forested hills and the steep Black Sea coast to Yalta, the site of the famed Second World War conference that saw the world divided up between East and West. Farther east, I’d visit the ancient Greek colony of Kerch, the thumb of Crimea’s fist. A port city – separated from the Russian mainland by a narrow stretch of water – it is the hub of the Kremlin’s effort to win Crimean hearts and minds with a massive infrastructure campaign.

Kerch was also the site of a November clash between the Russian and Ukrainian navies that illustrated just how easy it would be for this new cold war to become a hot one.

The pressure Mr. Legostov spoke of is highest in hardscrabble Bakhchysarai, the historic capital of the Crimean Tatars, a predominantly Muslim and Turkic-speaking group that make up about 10 per cent of the peninsula’s population.

The Crimean Tatars have always lived uncomfortably under Russian rule. In 1944, they were deported en masse to Central Asia by Stalin, who accused them, without evidence, of collaborating with the Nazis during the Germans’ three-year occupation of the peninsula. An estimated 8,000 Crimean Tatars died as they were shipped, in cattle cars, more than 4,000 kilometres east to what was then Soviet Central Asia. Tens of thousands more died during 45 years of enforced exile, including many who were sentenced to hard labour in the gulags of the Soviet Union.

The Crimean Tatars led the resistance to reunification with Russia, staging a massive pro-Ukrainian protest less than three weeks before the 2014 referendum, and then largely boycotting the vote itself. After annexation, they were an obvious target for Russia’s campaign to reset the rules here.

Dilyaver Memetov and his family had just gone back to bed after morning prayers on May 19, 2016, when men from Russia’s Federal Security Service, or FSB, came to their small home in Bakhchysarai on a muddy road that gives quiet testament to the uneven nature of the Kremlin’s largesse. About a dozen officers, wearing masks and carrying assault weapons, searched the home for several hours before arresting Dilyaver’s father, Remzi.

“It was like a scene from a Soviet film about the German occupation,” 25-year-old Dilyaver recalls. “I asked, ‘Where are you taking my father?’ They told me, ‘He will only be gone for 15 minutes so we can do some checks.’ Well, those 15 minutes have lasted for three years.”

Dilyaver Memetov and his mother, Elmira. Mr. Memetov's father, Remzi, was arrested three years ago.The Globe and Mail

Remzi Memetov was sentenced to nine years in prison for membership in Hizb ut-Tahrir, an international Muslim organization that calls, in Crimea and elsewhere, for the peaceful creation of a state governed by Sharia law. The group exists legally in Ukraine and many Western countries, but is banned as “extremist” in Russia.

In total, at least 30 Crimean Tatars have been arrested on charges of membership in Hizb ut-Tahrir or for participating in that pro-Ukrainian rally in 2014. Human-rights groups say another 44 have disappeared from their homes following raids by masked men. Although some of those have since been allowed to return home, six were found dead, their badly beaten bodies dumped in shallow graves; 19 remain missing.

Nariman Dzhelalov, the co-ordinator of the Mejlis, an elected body that represented the interests of Crimean Tatars until it was outlawed by Russia in 2016, says he sees a concerted effort to, once more, drive the Crimean Tatars from their land. The Crimean Tatars aren’t the only ones who are leaving: Some 28,000 Crimeans are officially registered in other parts of Ukraine as internally displaced people, though the real number left stranded is believed to be roughly double that.

“Today, people talk about hybrid deportations, where you’re not forced out, but they do everything possible to make you leave,” Mr. Dzhelalov had told me over tea at a Crimean Tatar restaurant in Simferopol. “It’s basically an international crime – Crimea is an occupied land, and people are being made to leave it.”

Nariman Dzhelalov, co-ordinator of an elected (and outlawed) body for Crimean Tatars, gives an interview in a café in Simferopol.The Globe and Mail

Certainly the price keeps rising for those who speak out. Emil Kurbedinov, a lawyer who represents Mr. Memetov and many other politically sensitive defendants, was himself jailed for five days in December, ostensibly over a photo he posted on Facebook in 2013 – a year before the annexation – of a Hizb ut-Tahrir rally. He says the real reason was his decision to defend Bohdan Nebylytsya, one of the 24 Ukrainian sailors taken prisoner after their ships were boarded and seized by the Russian navy off the coast of Crimea this past November. (Mr. Legostov is also involved in defending the sailors; both lawyers say they believe the conviction of all 24 has been ordered by the Kremlin.)

Earlier this month, Russia’s justice ministry called on the Crimean Bar Association to expel Mr. Kurbedinov, a move, if approved, that will almost certainly end his legal career. “Anyone who thinks differently than the government wants them to think is labelled an extremist or a terrorist,” Mr. Kurbedinov tells me, in his booming courtroom voice, when we meet at his office, where the waiting room is bustling with Crimean Tatars seeking his help.

Emil Kurbedinov was lawyer for the Ukrainian sailors arrested during the Kerch incident. Now, Russian officials are pressing the Crimean Bar Association to disbar him.The Globe and Mail

But others express sympathy for Russia’s iron first. Aidar Ismailov, the deputy mufti of the main mosque in Simferopol – which has accepted Moscow’s rule so completely that it airs Russian state television in the lobby – argues that Russia’s move against groups such as Hizb ut-Tahrir and the Mejlis was necessary to restore order in Crimea after the “mess” of Ukrainian rule, which permitted such organizations to exist. It is the duty of Crimean Tatars, he says, to accept that they now live in Russia.

Life has improved under Russian rule, Mr. Ismailov says, pointing to such infrastructure projects as a giant new mosque under construction on the outskirts of Simferopol. (The city’s main Russian Orthodox church has already been refurbished; a sign outside it says the work was done “under the personal patronage of V.V. Putin”). Mr. Ismailov says Western sanctions constitute the real human-rights crime here.

But his pro-Russian perspective is rare among Crimean Tatars. As I leave the mosque after our interview, I’m stopped by a worshipper. “I hear you are from Canada,” the man whispers in Russian as we stand on the snowy street. “Can you tell me how to seek political asylum?”

The graceful port of Sevastopol has a special place in Russian lore. During the Crimean War of the 1850s, Imperial Russian troops famously defended the city through an 11-month siege by British, French and Turkish soldiers, before finally surrendering. That brave history was repeated during the Second World War, when Soviet soldiers held out for 250 days against superior German forces.

The events of 2014 are referred to in Russian media as the “third defence of Sevastopol.” Ukraine, outside of Crimea, is portrayed not as pro-Western but as openly fascist, with Russian TV exaggerating the influence of far-right groups who supported the revolution in Kiev. The Kremlin, in that narrative, could not allow Russian-speaking Crimea to be overwhelmed by neo-Nazi Ukrainians. The “little green men” saved the day.

But perhaps the biggest reason Mr. Putin sent troops into Crimea was more specific: Sevastopol. The deep-water port remained home to the 45 warships of Russia’s Black Sea Fleet even after the fall of the Soviet Union, under an agreement between Moscow and Kiev that Mr. Yanukovych controversially extended to 2042.

As Mr. Putin made clear in a Kremlin-produced documentary about the events of 2014, he was determined that Sevastopol never fall into the hands of NATO.

“Are there any circumstances under which you would be ready to give away Crimea and Sevastopol?” the documentary’s host asks Mr. Putin.

“What?” replies the Kremlin boss. “Have you lost your mind?”

After watching the voting in Simferopol, I had spent the night of the 2014 referendum in a jubilant Sevastopol. The evening’s soundtrack was a mix of celebratory car horns and elated chants of “Ross-ee-ya!”

My hotel was a Best Western, which sat just down the street from a McDonald’s. Both brands are gone now, in accordance with Western sanctions that were intended both to punish Mr. Putin’s inner circle and to make it as difficult as possible for the Kremlin to integrate Crimea with the Russian mainland. The sanctions have turned the peninsula into an economic twilight zone largely disconnected from the global economy.

The former Best Western has reverted to its Soviet-era name, the Hotel Sevastopol, with a Trip Advisor certificate of merit from 2013 hanging above the reception desk as the only reminder of the time in between. The McDonald’s is now Mir Burger (or “Peace Burger”), with the McChicken rebranded as the “Czar’s Chicken.”

You can only pay with rubles or a Russian credit card. Foreign credit cards don’t work in Crimea.

But Mr. Putin got what he wanted: The Black Sea Fleet remains firmly ensconced here.

“An historic truth was restored,” Lena, a middle-aged guide, tells me after a choppy boat tour of the city’s harbour, during which she pointed out the destroyers and submarines at dock, listing off their impressive military capabilities from her even more impressive memory.

As we float by a white coast-guard vessel, she says, “This is the type of boat that stopped the recent Ukrainian aggression at Kerch,” referring to the November clash at sea during which the Russian side did all the shooting.

Natalia Alexandrovna, who runs a souvenir shop on the neatly kept waterfront, sees things in a different light. “Crimea is just a big military base now,” she says, sighing. Fearing retribution for her comments, the 59-year-old gives only her first and middle names. “There was a euphoria back then,” she continues, referring to the referendum on joining Russia. “Now, many regret it, even if they are afraid to say it.”

A two-hour drive east of Sevastopol lies the port city of Yalta, where Stalin, Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill divvied up postwar Europe, setting the stage for the first Cold War, which ended with the 1991 fall of the Soviet Union.

The successor conflict that began in 2014 has seen Moscow respond to the West’s sanctions with five years of what has come to be known as “hybrid warfare” – instigating a separatist uprising in the eastern Donbass region of Ukraine that has left more than 10,500 people dead, while deploying cyberattacks and electoral interference to destabilize Kiev’s Western allies.

Foreign-policy experts I met with in Moscow say that Mr. Putin’s preferred ending to this second cold war would be something like another Yalta agreement – a great-power understanding that once more divides the world into clear spheres of influence – and with Ukraine, all of it, once again Moscow’s alone to manage and meddle with. The Kremlin, analysts say, would even be willing to make concessions elsewhere, perhaps in the Middle East or on the Korean Peninsula, to get its way in a country Mr. Putin views as little more than a renegade province.

But this new contest between Russia and the West feels unlikely to end any time soon, and Yalta is one of the places where the chill winds are strongest, despite the palm trees and chic stores that feel right out of southern France. Where cruise ships once disgorged 10,000 tourists a year, today a graffiti artist’s impression of Mr. Putin – holding the wheel of his own ship, while a Russian fighter jet streaks overhead – looks out over Yalta’s boardwalk.

But there are few tourists for him to see. The luxury cruise ships that circle the ports of the Black Sea no longer stop in the limbo that is Crimea. And although the Russian government claims, via Twitter, that record numbers of tourists are arriving in Crimea, the figures appear to include all visits, including day trips by officials and longer stints by work gangs building the infrastructure projects.

Ahead of my arrival in Crimea, I had requested interviews with the manager of the Livadia Palace, site of the 1945 summit meeting (and now a museum), as well as the head of a nearby vineyard. I wanted to ask how the tourism industry has fared over the past five years. Both said I needed to first get permission from the regional government in Simferopol, which subsequently ignored my e-mail.

I’m left to wander Livadia on my own, with just a handful of other visitors. At the end, I find a shop selling souvenirs that range from bronze busts of Russia’s last czar, Nicholas II (who made Livadia his summer residence during the final years of his rule) to statuettes of Stalin, Roosevelt and Churchill.

There are also T-shirts and lapel pins with slogans celebrating the region’s more recent history. “Khrushchev gave up Crimea – Putin took it back!”

Heading east out of Yalta, a multilane highway now under construction promises, when completed, to transform the 200-kilometre drive between Simferopol and Kerch from four bumpy hours to two smooth ones.

Astride it are other, more sinister signs of the new regime. Among them: a three-vehicle mobile radar battery that is part of a massive military buildup on the peninsula in recent months, one that has led to talk that the Kremlin may be contemplating fresh military action – or at least trying to escalate the pressure on Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko – ahead of Ukraine’s presidential elections this spring.

Closer to Yalta stands a five-metre-high metal fence, topped with security cameras. Beyond it is a compound once used as a private resort for Soviet leaders dating back to Mr. Khrushchev. Today, locals say, it has been refurbished as Mr. Putin’s lavish new personal residence in the land he captured.

At the end of the drive is the once-forgotten port of Kerch. Since last year’s completion of the $4.7-billion Crimean Bridge – Europe’s longest, at slightly more than 18 kilometres – the city has become the nexus of a new transit route physically connecting Crimea to the Russian mainland. Kerch has also become a hot spot for international conflict. The Nov. 25 naval clash, which saw Russian warships fire on, and then board, three Ukrainian vessels as they tried to cross from the Black Sea to the smaller Sea of Azov, took place in the narrow Kerch Strait that lies between here and the Russian mainland.

From the top of Mount Mithridat, in the centre of the city, one of the three Ukrainian ships – the black-hulled military tugboat Yany Kapu – is visible in the harbour. It’s blocked in by Russian coast-guard vessels, to prevent any sudden attempt at escape.

“People in Kerch are happy; we can be across the bridge in Anapa [on the Russian mainland] in 40 minutes, and we can travel to Simferopol in just two hours,” says Claudia Lushkina, a rotund 70-year-old whom I encounter on the mount. The travel times are optimistic (Anapa is at least a two-hour drive), but Ms. Lushkina, who worked in a kindergarten before she retired, says her pension has also gone up since Crimea joined Russia.

It’s a statement that draws protest from a woman nearby who overhears us. Yes, pensions went up, but so did prices, she says, shrugging.“We live the same now as we did before.”

But the second woman won’t tell me her name. “I have one daughter who lives in Ukraine, and another in Russia,” she explains. “I’m in favour of friendship between nations.”

Back in Simferopol, Teenagers play ball on Pushkina Street.The Globe and Mail

On my way out of Crimea, I stop once more in Simferopol, this time to meet three young people involved in the local arts scene. It’s a Saturday night, and we get together in the heart of the Crimean capital – a newly opened café just around the corner from the city’s pedestrianized shopping and nightlife district – but there’s a depressed feel to the conversation. The three joke that coffee with a foreign journalist is the only thing on the cultural agenda that night.

“After we joined Russia in 2014, everything went into decline. There were fewer events, less motion. Everybody is just staying home and becoming more introverted,” says Artur Golovakha, who promotes concerts and events at Konservatoria, a local art house. But there’s nothing showing at Konservatoria this evening. “No bands will come here any more, at least no interesting ones.”

The situation has improved marginally in the past couple of years, as outrage over the events of 2014 starts to recede. But Mr. Golovakha, 29, whose face is framed by a brown beard, said most foreign musicians – as well as many Russian acts hoping to book tour dates in the much bigger Ukrainian market – continue to give Crimea a pass. He blames the Western sanctions, as well as Ukraine’s policy of banning anyone who enters Crimea via Russian territory: “The sanctions aren’t just affecting the [Russian] government, but also ordinary people who would just like to see a quality show, to enjoy some culture,” he tells me as he sips his Americano.

It’s a problem the Kremlin seems attuned to. Last summer, during a visit to Sevastopol, Mr. Putin ordered the construction of a cultural centre that would be affiliated with both the Hermitage museum in St. Petersburg and the renowned Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow. “Let’s not drag this out, all right? When will the drafts be ready?” Mr. Putin said, according to a Kremlin transcript of his meeting with Crimean officials.

But it’s not just the sanctions that are turning Crimea – which writers such as Mikhail Bulgakov and Anton Chekhov once visited in search of inspiration – into an artistic backwater. One of Mr. Golovakha’s friends, Svetlana Shokhina, a 22-year-old amateur photographer who moved from St. Petersburg to Crimea immediately after the annexation, said she has started censoring her own work. Ms. Shokhina says she recently began a project – one that would reference the fabled three wise monkeys who see, hear and speak no evil, in a commentary on the failings of local officials – then abandoned it. “Nobody wants problems. Nobody wants to go to jail.”

Despite all that, the three young adults say they’re happy that Crimea is under Russian rule. Ms. Shokhina, as an outsider, could not vote in 2014, but Mr. Golovakha and his friend Stas Kotenko say they both voted in favour of splitting from a Ukraine they believed was turning against its Russian speakers to the extent that annexation by Moscow was “the lesser of two evils.”

They say they’d vote the same way today. “I think it’s turned out fine. I expected worse,” says Mr. Kotenko, a 23-year-old event promoter who sports earlobe-stretching black earrings. He says relations between Russia and Ukraine will improve only when Ukraine elects a president who accepts what has happened in Crimea and “lets it go” – thereby allowing Crimeans to escape their purgatory.

When I ask them what they miss, the three start chatting about their pre-2014 lives. Mr. Golovakha says he pines to be able to download apps for his phone, or buy things on eBay, without using a virtual private network (VPN) and fake address. Ms. Shokhina recently had to have cosmetics delivered to her sister’s address in Moscow, and then mailed from there to Simferopol because the online retailer refused to sell directly to a resident of Crimea.

Foreign food is another rarity – thanks to the Kremlin’s countersanctions, which ban the import of a long list of Western agricultural products. “I miss Dutch cheese!” Mr. Kotenko says with a moan and a grin.

Svetlana Shokhina, Stas Kotenko and Artur Golovakha give an interview in Simferopol about the cultural changes Russian rule has brought to Crimea.The Globe and Mail

Tamila Tasheva misses something more substantial. She longs to see her home and family in Simferopol. The 33-year-old is one of the tens of thousands of Crimeans who choose to live elsewhere in Ukraine rather than at home, under Russian rule. As the head of Crimea SOS, a non-governmental organization that supports Crimean exiles, Ms. Tasheva wouldn’t be welcome in Mr. Putin’s Crimea, even if she chose to return.

Ms. Tasheva last visited Simferopol in January, 2014. She was already living in Kiev at the time – an active and thrilled participant in the pro-Western revolution taking place – when she made a trip to visit her parents and sister. Even then, more than a month before the appearance of the “little green men,” she says she could sense the Kremlin’s effort to pry Crimea and Crimeans away from Ukraine. There was heavy propaganda on Russian-language TV, she says, that presented the uprising in Kiev as violent and controlled by fascists. Crimeans, she says, quickly became convinced of the need to separate from the rest of Ukraine.

Ms Tasheva sees people such as Mr. Golovakha and his friends as victims of propaganda. She supports the Western sanctions, even as they make life harder for her relatives in Crimea. “I’m sorry, but [the Russian] government has committed an act of aggression,” she says. “We can’t reward that.” And Ms. Tasheva says the question of her homeland, and thus this new cold war, is far from settled. Crimea, she declares, will return to Ukraine after Mr. Putin leaves office. “We just don’t know if that’s five years away or 10.”

It’s unclear, I point out, whether change will come even then. The most prominent Russian opposition figure, Alexey Navalny, hasn’t promised to return Crimea should he become president – he has agreed only to hold another referendum.

I ask Ms. Tasheva what she thinks the result of a free and fair referendum would be. After a pause, she admits that, given all the changes imposed by Moscow, she doesn’t know her homeland as well as she once did. “Crimea,” she says with a sigh, “is not what it was before 2014.”

At the Russian-Ukrainian border, a guard checks the documents of a driver trying to cross.The Globe and Mail

Mark MacKinnon

Mark MacKinnon