Mark Whittle of Wales takes a breather at the top of Wright Pass. The summit of Wright Pass on the Dempster Highway marks the border between Yukon and Northwest Territories.WERONIKA MURRAY/The Globe and Mail

When Martin Like drove up the Dempster Highway during a location-scouting trip in 2006, he had a clear idea of the kind of ultramarathon race he wanted to organize: one that would be as close as possible to a real adventure. The native of Brecon, Wales, said he was looking for “a genuine ballsy challenge.” And the 6633 Arctic Ultra was born.

Like, now the race director, has achieved his goal. Since the first edition in 2007, the 6633 has earned a reputation as one of the most difficult foot races in the world. Taking place in the first few weeks of March, the 6633 – the race takes its name from the latitude of the Arctic Circle, 66 degrees 33 minutes north – is long, cold and over difficult terrain. And did we mention the cold?

The 6633 participants compete in two distances, neither of which is easy or cheap: 120 miles (approximately 193 kilometres), with an entry fee of up to £2,950, or about $5,050; or 380 miles, with an entry fee up to £3,250. Aside from a small support staff on hand in case of injury or sickness, the athletes race without assistance. The only thing the racers are given is hot water at predetermined checkpoints. The competitors pull all their supplies behind them in a sled.

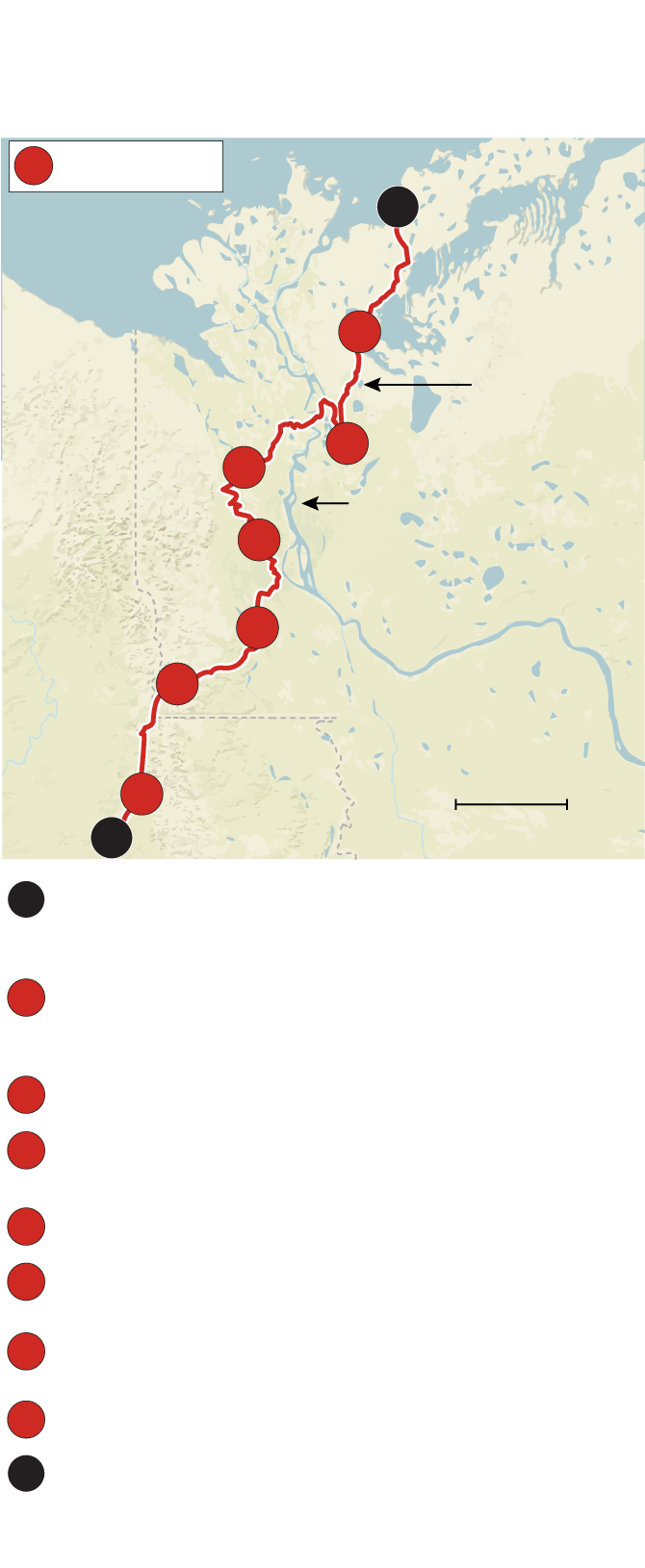

The route starts in Eagle Plains, Yukon, and follows the Dempster Highway northeast across the Arctic Circle and the Northwest Territories border to Fort McPherson. That’s the finish line for the 120-mile race, which can take up to three days.

From there, the athletes in the 380-mile competition travel by ice road to Aklavik, NWT, and then on to Tuktoyaktuk on the Inuvik-Tuktoyaktuk Highway, Canada’s only road to the Arctic Ocean. The 380-mile event can take eight or nine days, which is the maximum time allowed.

How tough is it to finish? On average, fewer than 30 per cent of a field comprising about 20 competitors (the maximum is 30) reach the finish line. This year, there were four competitors in the 120-race, 14 in the 380-mile.

The 6633 Arctic Ultra is a self-supported race – the athletes carry their supplies for the entire race in their pulk sleds (the wheels can come off and the sled like a toboggan). At checkpoints, dotted along the route 70-80 kilometres apart, they can only get hot water. Cynthia Fish of Canada takes a break on her way into Fort McPherson.WERONIKA MURRAY/The Globe and Mail

For Montreal’s Cynthia Fish, a two-time 120-mile race finisher and the only Canadian to participate in 2019, the 6633 was the toughest event she’s ever signed up for.

“Self-reliance is a big element of this race," Fish says. “It’s long, it’s dark, and it’s cold. The dark can be unsettling. … You need the gear, you need to practise with the gear and you need to be able to keep putting one foot in front of the other for the longest amount of time you can imagine, and then some.”

For Paul Watkins of Australia, who won this year’s 380-mile race, the difficulty of this event lies in the discipline required to manage one’s physical well-being, progress and thoughts in such difficult conditions.

“The extreme cold, the sleep deprivation and the consistent and cumulative physical toll are what place the difficulty of this race over the top," Watkins says.

"On paper, the math doesn’t look that bad. The required speed to get the [total] distance done in the time limit isn’t horrific, the difficulty lies in the details. The discipline to eat regardless of the weather, of how you feel, whether you can be bothered, whether you are hungry or not. The constant management of your temperature, dealing with little niggles. Managing your attitude and staying positive day after day, and especially night after night.”

Two-time participant Kevin Webber from Britain says that the solitude sets the 6633 apart from other races.

“I have run several multiday ultramarathons but they have all been stage races. Each day has a route, but at the end you get 12-plus hours off before the next day. On the 6633, there are no breaks. … There is a camaraderie on the other races as you meet the other athletes in a relaxed manner at the end of every day. The 6633 is lonely, and the clock is always ticking.”

For British ultrarunner Hayley White, the only woman who finished the 380-mile race this year, it’s the sheer extreme conditions that made this race so brutal. “I’ve done many multistage races and single ultras but nothing as demanding as this. It makes Marathon de Sables [the world’s best-known multiday ultramarathon, which takes place in the Sahara Desert] look like a week-long running vacation.”

Clockwise from top left: Hayley White of Britain is the only woman to finish this year's 6633 Arctic Ultra; Paul Watkins from Australia, this year's 380-mile race winner, grabs a meal on the go on the Aklavik ice road; Kevin Webber of Britain was diagnosed with terminal prostate cancer four years ago; Against all odds he not only continued to run after starting his treatment, but now competes in more races than ever before; Ireland's Patrick O'Toole on the Aklavik ice road wears tape on his face to help protect him from cold and wind; Mark Whittle of Wales, tied for fifth with Hayley White, whom he raced alongside the entire way.WERONIKA MURRAY/The Globe and Mail

Watkins first attempted to complete the race in 2017 but withdrew after reaching Fort McPherson. He decided to return in 2019. “I know all the platitudes of ‘Just turning up is a victory,’ but for me, the ‘failure’ of my attempt in 2017 left a deep void within me,” the Australian said shortly after his win this year.

“I knew I could come back and execute a very different race. I was an absolute bundle of nerves and insecurities for the weeks before the race, right up until the start. Literally within hours of starting I felt at peace – I knew I was ready, I knew what I had to do and I felt unbelievably ready to do it.”

THE 2019 6633 ARCTIC ULTRA RACE

Considered the toughest ultra marathon

in Canada, on average fewer than 30 per cent

of competitors reach the finish line.

#

checkpoints

Tuktoyaktuk

F

Husky Lakes

Beaufort

Sea

7

Inuvik-

Tuktoyaktuk

highway

6

5

Mackenzie River

4

3

YUKON

2

NORTHWEST

TERRITORIES

0

60

1

KM

S

Eagle Plains

Eagle Plains (0 km) The start is a solitary

hotel and fuel stop and the only place with

a meal, bed and gas until Fort McPherson.

S

Arctic Circle (36 km): Past this is “Hurricane

Alley”, known for very strong Katabatic winds.

Trucks are regularly blown over here.

1

James Creek (114 km)

2

Fort McPherson (182 km): Leaving here is a

new route to the finish line. To Aklavik,

it is a private ice road.

3

Mid Peel River (258 km)

4

Aklavik (339 km): From Aklavik, more solid

ice. This is a non-stop section to Inuvik.

5

Inuvik (459 km): Showers, warm rooms,

beds and cooking facilities.

6

Gateway (529 km)

7

Tuktoyaktuk 617 km)

F

CARRIE COCKBURN / THE GLOBE AND MAIL,

SOURCES: GOOGLE MAPS, ESRI, 6633 ARCTIC ULTRA

THE 2019 6633 ARCTIC ULTRA RACE

Considered the toughest ultra marathon in Canada,

on average fewer than 30 per cent of competitors

reach the finish line.

#

checkpoints

Tuktoyaktuk

F

Beaufort

Sea

Husky Lakes

7

Inuvik-

Tuktoyaktuk

highway

6

5

Mackenzie River

4

3

YUKON

2

NORTHWEST

TERRITORIES

0

60

1

KM

S

Eagle Plains

Eagle Plains (0 km) The start is a solitary hotel and

fuel stop and the only place with a meal, bed and gas

until Fort McPherson.

S

Arctic Circle (36 km): Past this is “Hurricane Alley”,

known for very strong Katabatic winds. Trucks are

regularly blown over here.

1

2

James Creek (114 km)

Fort McPherson (182 km): Leaving here is a new route

to the finish line. To Aklavik, it is a private ice road.

3

4

Mid Peel River (258 km)

Aklavik (339 km): From Aklavik, more solid ice.

This is a non-stop section to Inuvik.

5

6

Inuvik (459 km): Showers, warm rooms, beds

and cooking facilities.

7

Gateway (529 km)

Tuktoyaktuk 617 km)

F

CARRIE COCKBURN / THE GLOBE AND MAIL,

SOURCES: GOOGLE MAPS, ESRI, 6633 ARCTIC ULTRA

THE 2019 6633 ARCTIC ULTRA RACE

Considered the toughest ultra marathon in Canada, on average fewer than 30 per cent

of competitors reach the finish line.

checkpoints

#

Tuktoyaktuk

F

Husky Lakes

Beaufort

Sea

7

Gateway

Inuvik-Tuktoyaktuk

highway

6

Inuvik

Aklavik

5

Mackenzie River

4

Mid Peel River

3

Fort McPherson

2

James Creek

YUKON

NORTHWEST

TERRITORIES

0

60

Arctic Circle

1

KM

Eagle Plains

S

S

Eagle Plains (0 km) The start is a solitary hotel and fuel stop and the only place

with a meal, bed and gas until Fort McPherson.

1

Arctic Circle (36 km): Past this is “Hurricane Alley”, known for very strong Katabatic

winds. Trucks are regularly blown over here.

2

James Creek (114 km)

Fort McPherson (182 km): Leaving here is a new route to the finish line.

To Aklavik, it is a private ice road.

3

4

Mid Peel River (258 km)

Aklavik (339 km): From Aklavik, more solid ice. This is a non-stop section to Inuvik.

5

Inuvik (459 km): Showers, warm rooms, beds and cooking facilities.

6

7

Gateway (529 km)

F

Tuktoyaktuk 617 km)

CARRIE COCKBURN / THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCES: GOOGLE MAPS, ESRI, 6633 ARCTIC ULTRA

Patrick O'Toole of Ireland arrives in Tuktoyaktuk.WERONIKA MURRAY/The Globe and Mail

Before the start, the participants go through a mandatory kit check by race organizers and a survival exercise, in which they have to demonstrate that they are capable of being self-sufficient. As well as physical training, White left little to chance in her preparations: back home before the race, she slept outside in her bivvy bag (a personal-sized waterproof shelter), learned to use the camping stove with mitts on and put food in the freezer to see if she was still able to eat it frozen solid.

Because the participants get no respite over the course of the race, any mistakes made along the way can force them to drop out. Webber turned up at the start line with a bad cold, went too far on the first day before resting and didn’t time his meals right. The combination of all those factors left him feeling unwell and forced him to withdraw 48 hours into the race. Webber admits that his training wasn’t optimal. Instead of sticking to a plan, he participated in two ultramarathons and ran 20 or so marathons in the months leading up to this year’s 6633.

This approach may seem unorthodox to an average runner, but there is nothing average about Webber and his running journey. In 2014, he was diagnosed with terminal prostate cancer and given two years to live. More than four years since his diagnosis, Webber is here, running, and through his participation in ultramarathons all over the world, has raised more than $170,000 for Prostate Cancer UK, an organization that finances prostate-cancer research and strives to improve medical care for men living with and recovering from prostate cancer.

Before his diagnosis, Webber was a recreational runner with a handful of marathons and two ultramarathons under his belt. After his first day of chemotherapy, he decided to go for a run. “I managed just three slow miles, I felt sick and worn out but elated that, despite cancer taking away my future life, it had not taken away my ability to put one foot in front of the other. I realized that some things could still be in my control.”

Thirteen weeks into his treatment, Webber ran the Brighton Marathon, and the London Marathon shortly after.

Mark Whittle and Hayley White walk through a blizzard on the Peel River ice road. Despite warmer than usual weather during the first few days of the event, only 6 out of 15 athletes participating in the 380-mile race reached the finish line.WERONIKA MURRAY/The Globe and Mail

Webber participated in the 6633 last year and completed the 120-mile race. He loved the challenge, so he came back this year to see if he could do 380 miles.

“I couldn’t. It was a lesson for me.”

But he says, in some ways, he has been more successful by failing. “You see, I dared to dream. I pushed myself to the limit, now I know what that feels like. If you never go into something where there is physical jeopardy, you will never know where that line is. Most people never do and that is sad. It’s easy to have an average life and stay safe. To me, that is a wasted opportunity of life.”

Didier Da Costa is photographed under the Northern Lights on the Peel River ice road in the Northwest Territories.WERONIKA MURRAY/The Globe and Mail