You smell “the show” before you see it – 200 cannabis plants, tucked inside a 120-year-old barn on a sloping acreage overlooking central British Columbia’s Slocan Valley. In one room, 40 plants are nearing maturity. The pungent flowers will be harvested in two weeks, hung to dry and sold for between $1,500 and $1,800 a pound to distributors moving B.C. bud to illegal dispensaries across Canada.

On the other side of the property, a larger building is under construction. The roof is up, and the interior is partially finished with white walls and rows of plastic bins waiting to be filled with bushy marijuana plants.

For the couple that owns the property, this second building is supposed to be their ticket into the legal recreational marijuana market. They’ve put $400,000 into the project and expect to spend at least as much again trying to bring it up to Health Canada standards for a Micro Cultivation licence. Six months into legalization, however, they still have not submitted a licence application and construction has come to a halt.

The couple, who agreed to a tour of their property on condition of anonymity, say the application process is vague, expensive and fraught with uncertainty. It is a common sentiment across rural B.C., the longtime heart of Canada’s cannabis industry, where small and mid-sized growers from the illicit market are struggling with Health Canada’s new “micro” system.

The program, which launched in October alongside the federal legalization of recreational cannabis, permits small-scale cultivation and processing with lower infrastructure and security requirements than standard licences. It was designed, at least in part, to give incumbent growers a route into the legal system. However, the roll-out has been hampered by land-use restrictions, limited access to capital and a federal regulatory system that many growers say is too burdensome for a small-business approach to cultivation.

The process of getting a licence became even more daunting last Wednesday, when Health Canada changed its rules to require new licence applicants have a “fully built site” before they can submit an application.

“The new regulations further enhance an uneven playing field that is already favouring the development of large conglomerates at the expense of small growers,” said a group of six B.C. craft cannabis organizations, who issued a joint statement on Monday, following the change.

“Without a significant change in approach by the federal government, B.C.’s globally recognized craft cannabis sector is not likely to survive legalization.”

There are thousands of grey-market cannabis operations across British Columbia. Facilities like this one usually operate in a semi-legal environment: they are licensed under the old Marihuana Medical Access Regulations to grow cannabis for designated patients, but sell to illegal dispensaries as well. Mark Rendell/The Globe and MailThe Globe and Mail

Meanwhile, the legal cannabis system, dominated by massive publicly traded licensed producers, is struggling to meet the demand of consumers accustomed to high-quality illegal product grown largely in B.C. and sold across the country at lower prices than what’s available legally. Industrial-scale facilities have been plagued by growing problems and quality concerns. Supply remains strikingly short, even as licensed producers – none of whom are profitable – burn through hundreds of millions of dollars building facilities and trying to develop brands.

For both sides, there’s a lot at stake in the success of the micro program. Many rural communities in B.C. have come to depend on cannabis cultivation – at both a family farm and semi-industrial scale – to offset declines in traditional extraction industries such as logging and mining. Without a viable route into the legal market, thousands of craft growers in places such as the Kootenays, the Sunshine Coast, the Cowichan Valley and the Gulf Islands, could see their livelihoods vanish. Growers in more commercially oriented areas like the Okanagan and the Fraser Valley also face disruption.

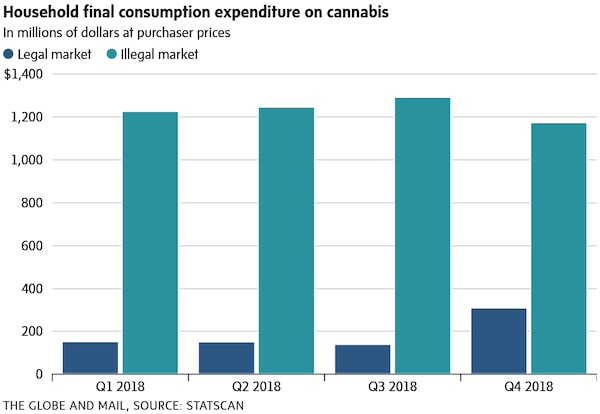

Likewise, the financial success of the Trudeau government’s project of Bay Street-led recreational legalization is at risk. According to Statistics Canada, around 80 per cent of cannabis consumed by Canadians in the first quarter post-recreational legalization was produced outside the legal system. Legal sales have barely increased in the months since.

Few illicit producers expect the unregulated market to remain viable over the long term; legal product will eventually glut the market and police are shutting down illegal sales channels. Still, legal cannabis companies, most of whom are fragile start-ups despite the amount of money they’ve raised, face protracted and financially damaging competition if the legal marijuana market cannot integrate large parts of the illegal system.

"We have extensive supply and extensive demand, so we’re not kicking and screaming into the new paradigm,” said Chris, a cannabis broker who runs an illegal online dispensary operating across the country, and who asked only to be identified by his first name.

"We want our supply chain to come in together. And in order for us to bring our supply chain in, we need to have micro licences,” he said.

The Globe and Mail

After recreational legalization on Oct. 17, Health Canada expected a flood of applications from the thousands of small and mid-sized growers operating in the black market and the so-called “grey market" – growers grandfathered in from the old Marihuana Medical Access Regulations (MMAR) who are allowed to produce medical cannabis for designated patients but who also sell to illegal dispensaries. As of March 31, only 150 Micro Cultivation and Micro Processing licence applications had been submitted.

“The federal government thought there would be so many micros in by now, but people are freaked, nobody wants to sign up, everything is stacked against them,” said the Slocan Valley grower, a man in his early 50s, who grows cannabis for his own medical use, but also sells to illegal dispensaries.

Health Canada has set up a separate queue to process micro applications, and approximately a quarter of the 150 applications are under active review. Only one micro licence has been granted: to a B.C. company that Health Canada declined to name.

On a Thursday in early April, around 150 black and grey market cannabis growers gathered in the Prestige Hotel in Nelson, a picturesque mountain town on the western arm of Kootenay Lake, with a population of around 10,000. The idea behind the Kootenay Cannabis Symposium was to bring together growers from across British Columbia and representatives from all levels of government, in the hope of tracing a path forward for the micro program.

"The outcomes of not transitioning [into the legal market] are unfathomable. We're talking about unemployment, homes and businesses for sale, empty storefronts,” Tracey Harvey, an instructor at Selkirk College in nearby Castlegar and a University of Guelph PhD candidate researching the impact of legalization on rural B.C., told growers gathered in the hotel conference room.

Because of its underground nature, it is impossible to know how large the cannabis industry is around Nelson. Ms. Harvey estimates that at least a quarter of the work force in the Kootenays is involved in the illegal or semi-legal production of cannabis. With marijuana money circulating through the local economy, the impact of the industry is likely far greater, she added.

“Cannabis legalization... wasn’t properly addressed by our provincial government who knew very well about the thriving underground cannabis industry, but did nothing to aid a transition. Now our province is scrambling, as they realize what a mess this is creating, particularly in the peripheral areas,” Ms. Harvey explained.

The 100 kilometre-long Slocan Valley, just west of Nelson, is home to hundreds of cannabis growers. The hillsides of the picturesque valley were once covered in illegal outdoor marijuana crops. Today, most Slocan growers use indoor hydroponic growing systems, in outbuildings, barns and basements. Mark Rendell/The Globe and MailThe Globe and Mail

One of the biggest issues is land use. Some municipalities, such as the Regional District of Central Kootenay around Nelson, recognized the coming impact of legalization early on and changed bylaws and zoning regulations to allow for cannabis cultivation. Most municipalities in B.C., however, have yet to update their rules to permit legal cannabis cultivation. Health Canada will not approve a licence application unless the facility is in line with local government regulations.

"In local government, many of us knew that legalization was coming... but everybody had their mind around dispensaries,” said Susan Chapelle, a former city councillor for Squamish, who now heads government relations for Pasha Brands Ltd, a Nanaimo-based cannabis company. “We didn't think about cultivation.”

At the provincial level, would-be legal growers are running into problems with the Agricultural Land Reserve (ALR), the land management system in place to protect British Columbia’s scarce arable land and food supply.

Last summer, the Agricultural Land Commission (ALC), which oversees the ALR, announced that municipal and First Nations governments can choose to prohibit most forms of cannabis cultivation on ALR land within their local boundaries. (Local governments cannot prohibit outdoor cultivation on ALR land or cultivation that takes place in converted agricultural buildings built before July 2018, or in buildings with soil floors).

The ALC also prohibits new concrete being poured on ALR land, unless a non-farm use exemption is granted. This creates a Catch-22 for indoor growers: their existing operations likely don’t meet Health Canada standards for layout and building materials, but they’re limited in their ability to build new facilities due to restrictions on new concrete slabs.

People lucky enough to have properly zoned land in a municipality amenable to cannabis still face significant hurdles. Micro cultivation sites are capped at 2,000-square-feet of growing space and have lower security and infrastructure requirements than traditional LPs. Still, between regulatory consultants, compliant building materials, and security infrastructure, the upfront cost to start a micro cultivation facility is typically estimated to be between $1-million and $2-million.

That cost puts micro licences beyond the reach of many B.C. growers running small and mid-sized facilities of fewer than 40 lights, to use industry parlance. These growers, operating in basements, garages, and outbuildings across the province may bring in enough money to support their families on an income comparable to a good middle-class salary. However, finding $1-million to $2-million, particularly when banks are reluctant to lend to businesses without financial paper trails, is a huge challenge.

“We don’t see a way in, unless we’re signing over everything that we’ve worked for to millionaires,” said Patrick Bonin, who, along with his father, owns a grey market medical cannabis company called The Melatonic Society.

His operation, run out of a yellow outbuilding in the hamlet of Ymir, about 30 kilometres south of Nelson, grows between 50 and 80 pounds of cannabis flower a year, which Mr. Bonin turns into CBD-rich oils for medical patients. Last year he sold around 10,000 bottles of cannabis extract, either directly to patients or through dispensaries.

Patrick Bonin runs The Melatonic Society, a grey-market cannabis oil company, out of a small outbuilding on his property in Ymir, 30 kilometres south of Nelson. Last year, The Melatonic Society sold around 10,000 bottles of CBD and THC oil, extracted from cannabis grown by Mr. Bonin. Mark Rendell/The Globe and MailThe Globe and Mail

It is a good family business, but Mr. Bonin does not see how to make the transition. Despite building a clean and controlled environment to produce medical-focused products, his facility will likely not meet Health Canada’s micro standards, not least because he grows with organic methods that don’t meet strict limits on microbial content in cannabis.

“They need to know when people are willing to play ball. We have our facility here. We’re willing to bring you in, tell us what can we upgrade… Don’t make us criminals,” he said.

There is a sense of extreme frustration among incumbent growers, who believe legalization was designed to sideline the existing industry. Instead of benefiting industry pioneers, so far the spoils of legalization have gone to a handful of licensed producers who got their start between 2013 and 2015, after the federal Conservative government introduced a commercial growing regime for medical cannabis.

"We put ourselves at risk, we developed products, we developed strains, we developed methods of growing, sales outlets… We’ve done all that, and now the government steps in and says great, you’ve proved the point, off you go small people, we’ve got it from here,” said Andrew Lauchlan, a grey market grower in Nelson, who is building a micro-cultivation facility and who owns a cannabis dispensary in Nelson.

With commercial medical licences in hand, companies such as Canopy Growth Corp., Aurora Cannabis Inc. and Tilray Inc. raised billions of dollars and built countrywide cultivation and distribution systems in anticipation of recreational legalization. Most black and grey market players weren’t given a legal way to prepare for the recreational market until last October, when the micro system came into force. They are still, for the most part, unable to access financing.

“The only thing people can do is group together... leverage all of their equity and roll the dice with five or six buddies," said a grower who runs a mid-sized, 70-light operation at the southern end of Slocan Valley. He agreed to a tour of his property on the condition of anonymity, as his company has submitted a micro licence application to Health Canada but continues to sell to illegal dispensaries.

The facility does close to $1.8-million in sales a year, earning profits of around $1-million, split between six partners, he said. Groups growing at this scale have a decent shot of making a transition into the legal system. People growing at a smaller scale will struggle.

David Robinson, who runs the Nelson branch of Pacific Northwest Garden Supply, one of B.C.’s largest hydroponic store chains, shares that view. He estimates that small and mid-sized growers in the Kootenays produce around 25,000 kilograms of cannabis a year, which he says is equivalent to around 60 to 70 micro cultivation facilities.

“The best chance we’ve got is to take the top 10 prospects of the area, get them to build out a micro facility or two, and then they’ll build out three, four, five and six... The person who had 24 lights will work for them. It’s a model that’s acceptable, because it’s better than total failure,” Mr. Robinson said.

The Globe and Mail

This is not the first time outside forces have rocked the industry. By the mid-1990s, B.C.’s iconic cannabis industry of hippies and draft dodgers growing weed on islands and mountainsides was largely replaced by indoor cultivators using hydroponic growing systems. The industry boomed, in large part due to exports smuggled into the United States.

“The 90s was a time when gangs were trendy, and that whole thing was going on, and organized crime,” said Mr. Robinson, who has been involved in the industry since the mid-1990s.

Today, organized crime is far less prevalent due to lower prices and less cross-border smuggling, Mr. Robinson said. In 1996, California voted to legalize medical cannabis, dramatically increasing supply south of the border. Then the attacks of September 11, 2001, led to increased border security, curtailing smuggling.

Luckily for growers, 2001 also saw the introduction of Canada’s Marihuana Medical Access Regulations, following a successful Charter challenge. The MMAR allowed patients to grow their own cannabis or designate other people to grow on their behalf. Cannabis entrepreneurs scrambled to lock up designated growing licences, and dispensaries popped up to take advantage of the legal grey area created by ongoing Charter challenges.

"We went from black to grey... and rode that wave for a good 15 years,” said Mr. Robinson.

Despite the new challenges posed by legalization, business models are emerging across B.C. to help growers into the legal system.

In Sooke, around 40 kilometres west of Victoria on Vancouver Island, real estate developer Ian Laing is piloting the idea of a “micropark.” On the empty half of his industrial-zoned Sooke Business Park, he is planning a complex of 53 units that he’ll rent to micro cultivators.

“We deliver the building, the zoning, the power to your electric room. The tenants are responsible to do the tenant improvements of their units. So they will need a budget of $300,000 to $500,000 depending on their method of growing," said Mr. Laing, who is also a director of Specialty Medijuana Products Inc., a licensed producer based in the Sooke Business Park.

The catch is that growers won’t be permitted to package their own product for sale directly to provincial wholesalers. BC Canna Park members have to sign a “processing and packaging agreement” with Specialty Medijuana, giving Mr. Laing’s company the first right of refusal for product grown in the micropark.

Christina Lake Cannabis Corp., a planned outdoor growing operation near Christina Lake, B.C., is only a kilometre or two from a U.S. border crossing. The valley where it is located used to be a popular smuggling route and the surrounding hills were filled with illegal outdoor production. Mark Rendell/The Globe and MailThe Globe and Mail

A related model is being developed by Pasha Brands and its subsidiary BC Craft Supply. Their plan revolves around sourcing cannabis from micro growers across the province, processing it in a facility in Nanaimo, and selling it under old black market brand names, which Pasha has acquired.

In return for the first right of refusal to buy cannabis grown by its micro partners, BC Craft Supply is sharing licensing costs and helping line up financing for craft growers. The company has already signed up several dozen growers, said CEO Patrick Brauckmann.

“With 100 micro cultivators in our supply chain, we’ll be producing 50,000 kilos of product per year,” he said.

The BC Small Cannabis Producer and Processor Co-op, funded by Vancouver-based Grow Tech Labs, is taking a co-op approach, while Craft Depot in Victoria is developing a broker model, connecting micro growers with buyers looking for small batch product.

In the lead up to Oct. 17, large LPs were also touring B.C. and offering partnership deals. This has died down in recent months, according to growers at the Nelson conference, but elements of Bay Street are starting to take note of B.C.'s small producers.

“Toronto money is looking at the industry in a new way, because they’ve deployed an enormous amount of capital for LPs, they see the craft world emerging, and they know there’s been some real challenges with large-scale LPs actually being able to deploy the capital properly,” Mr. Brauckmann said.

In Christina Lake, around 120-km southwest of Nelson, long-time grower Nicco DeHaan is hoping to tap that interest in B.C.’s incumbent growers. His company, Christina Lake Cannabis Corp., raised $2.4-million last year to acquire 32 acres of land in a breathtakingly beautiful valley only a kilometre or two from the U.S. border. The plan is to grow outdoors as well as process cannabis from micro-cultivators in the Grand Forks area.

The semi-arid region used to be a prime smuggling channel, and the surrounding hills were once covered with furtive grows. If everything goes to plan, the valley will soon be a field of legal pot, and the first thing U.S. visitors will see on crossing into B.C. will be rows of towering marijuana plants – a strain Mr. DeHaan developed over the years.

"The cannabis industry has been forced to be very diverse and adaptable as it is. It went from clandestine outdoor growing, to indoor, to medical storefronts everywhere in B.C.,” Mr. DeHaan said. “People were scared when that was happening, and they managed to pull through and evolve. This is another one of those changes.”

Mark Rendell

Mark Rendell