According to the OECD, Canada is the fifth most prolific country in the world for the production and transit of counterfeit electronics—stuff that can actually set fire to your home

Chris Robinson/Fuze

When you brushed your teeth this morning, did you spend much time considering the object you stuck, sleepily, reflexively, into your mouth? As it passed over your teeth, massaged your gums and scoured your tongue, did you wonder where it came from, how it was manufactured and by whom? Did you pause to think about whether it was doing the job it was supposed to do or that it could possibly be doing more harm than good? Did you ever stop and ask yourself: Is this plastic thing, this unremarkable and ubiquitous dental instrument, even real?

Toronto-based lawyer Lorne Lipkus has given a lot of thought to these questions. Because, as it turns out, even the lowly toothbrush has fallen under the rapacious eye of counterfeiters, and Lipkus is the man sometimes referred to as Canada's "anti-counterfeiting guru." And so he has learned as much about toothbrushes as he can. He has learned, for instance, what kind of glue should be used to hold the bristles in place and why the tops of the bristles should be rounded—because otherwise, they can slit your gums. "Imagine if they were cut straight across," Lipkus says. "You've just created a thousand knives."

There were no bloody gums involved in July 2008 (so far as we know), when Health Canada issued a recall for the Oral-B Classic 40 Medium toothbrush. It received a complaint that an insufficiently fastened bristle had become dislodged and stuck in a user's throat. The complainant, who'd purchased the offending implement at a Dollarama store, didn't require medical care, but the bristles were clearly a choking hazard. It turned out the toothbrush was a fake—Oral-B hadn't even made the Classic 40 Medium model in nearly a decade.

In the end, more than 750,000 phony toothbrushes were purged from Canadian stores, including Dollarama (which issued a voluntary recall). "They didn't take three-quarters of a million off one store or one chain," Lipkus says. "It was across the country. And they didn't get them all."

How could they? The counterfeit market had long been growing exponentially, and by 2008, it had exploded. Now, counterfeiting is big business—big, sophisticated and incredibly complex. Thanks to globalization, digital technology and lax law enforcement, the variety of counterfeit goods has become almost infinite, the quality of the fakes much higher (and retailing at higher prices) and the sale of these products far more widespread—mind-bogglingly, economy-cripplingly so. Counterfeits are everywhere, not only in flea markets and mom-and-pop dollar stores, but also in unwitting brand name chain electronics emporiums, autobody shops, grocery stores and, of course, all over the Internet. Counterfeit parts have been found on Canadian military aircraft and Air Force One.

A recent University of Guelph study found that 20% of sausages in Canadian supermarkets contained meats (including horseflesh) not indicated on their labels. No one knows how much fake fentanyl is responsible for deaths in the opioid epidemic. "There are two categories of counterfeits," Lipkus says, "and two categories only: anything and everything. Chairs are being counterfeited, flooring is being counterfeited, paint is being counterfeited. Pictures, screws, nails, security systems, electrical outlets. There's counterfeit coffee and mugs and sunglasses and iPhones and tape recorders. If you're wearing contacts, those are being counterfeited too."

A study conducted by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and the EU Intellectual Property Office estimates that, in 2013, international trade in counterfeit and pirated goods represented up to 2.5% of all world trade—about $461 billion (U.S.). A comparable Frontier Economics report prepared for the International Chamber of Commerce's anti-counterfeiting arm projected that, in just three years, these activities would drain $4.2 trillion (U.S.) from the global economy and put 5.4 million jobs at risk. Lipkus says Canada's counterfeit market is pegged somewhere between $20 billion and $30 billion but could be much higher.

That economic threat is real and enormous. But more pernicious, and less often discussed, are the myriad threats counterfeits pose to public safety. Your bogus earbuds could melt while you're wearing them. Fake heart medication could lead to a coronary. Counterfeit airbags and ball bearings and brake pads could wreak havoc on the highways. Counterfeit products are almost always inferior—they don't work properly or don't work at all. They break easily. They look or taste or act strange, funny, wrong. Last year, Interpol co-ordinated the seizure of 10,000 tonnes and one million litres of bogus and dangerous food and drink, including sugar cut with fertilizer and olives painted with copper sulphate to enhance their colour. In December, the safety-standards organization UL Canada evaluated 400 fake iPhone adapters; 397 failed basic safety tests, and 12 posed "a risk of lethal electrocution to the user."

Making matters worse, the manufacture, distribution and sale of fake goods is usually controlled by organized crime and has even subsidized terrorists. But the counterfeit economy is also so tightly entwined with the legitimate economy, it's almost impossible to separate and snuff out. In China, counterfeiting is a $400-billion (U.S.) business, with entire small cities and their respective tax bases, schools and transportation systems completely dependent on illicit manufacturing.

While China and Hong Kong are responsible for more than 80% of all counterfeit goods, Canada is, according to the OECD, the world's fifth most prolific country for the production and transit of counterfeit electronic goods. And yet, Canadian law enforcement agencies, courts and governments still don't treat it like the problem it so obviously is. The lax attitude hasn't gone unnoticed: In late March, U.S. President Donald Trump, for once echoing a position held by the previous administration, issued an executive order targeting trade abuses by several countries, including Canada, that singled out the transit of counterfeit goods. The edict was followed by a report from the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative, calling out Canada's refusal to boost border inspections for "in-transit counterfeit trademark goods and pirated copyright goods entering Canada destined for the United States."

Lorne Lipkus scrutinizes a pair of fake Oakley’s. Real ones have actually been known to deflect bullets. Fake ones do more harm to your eyes than good. Thousands of Team Canada jerseys that made their way into Canada before the 2010 Vancouver Olympics. Lorne Lipkus scrutinizes one of thousands of Team Canada jerseys that made their way into Canada before the 2010 Vancouver Olympics.

Chris Robinson/Fuze

That has left the fight against counterfeiting largely up to a small cadre of self-appointed experts like Lipkus, who deploy a host of strategies, both ingenious and mundane, to combat the problem. Lipkus believes most people still equate counterfeiting with ersatz luxury goods and consider it a kind of victimless crime. He insists this is a mistake. "Everyone is quick to talk about luxury bags," Lipkus says. " What do I care about Louis Vuitton or Gucci? I'm not losing money. But it's so far from that now that we're fooling ourselves if we focus on that."

Pacific Mall is about an hour's drive north of downtown Toronto, depending on traffic. It's billed as the largest indoor Chinese shopping mall in North America, with hundreds of stores (none of them major retailers, except for telecoms like Rogers and Bell) arrayed along aisles named after streets in Hong Kong. It's a lively, even raucous, place, where smiling clerks beckon passersby into shops that sell everything from ginseng and jewellery to dancing shoes and dried durian, almost all at discounted prices.

When Lipkus walks down these same aisles, the smiles vanish and the shops suddenly close their doors. Aside from being the largest mall of its kind, Pacific Mall is also, according to Lipkus, the largest retail outlet for counterfeit goods in Canada. It is packed with fakes—janky fidget spinners, faux Lego Superman toys in boxes emblazoned with the Avengers logo, $3 Blu-ray discs of recent blockbusters—but these are just bad knock-offs. The real problem is counterfeits that are seemingly so well manufactured and their packaging so precise (right down to dummy safety-certification holograms) that many consumers can't even tell they're fake. Or don't care. "It's not usual for somebody to go to Pacific Mall and buy a Chanel purse for $50 and think it's real," says Daryl Somes, a private investigator who often works with Lipkus.

Lipkus, who is 64 and has the wry, cuddly air of an off-duty mall Santa, has been fighting counterfeiters since 1985. The litigation lawyer was hired by Club Monaco to shut down multiple vendors at a flea market selling fake T-shirts at four for $10. Lipkus got an Anton Piller order, which allows for the seizure of merchandise to use as evidence. Soon, he was representing 150-odd rock bands and the company that created Barney, the once-beloved purple dinosaur. Along the way, he opened his own boutique firm, Kestenberg Siegal Lipkus LLP. In 1993, the firm started to represent Disney, which, understandably, opened up many other doors. Lipkus has since been involved in the removal of counterfeit products on behalf of more than 100 brands, including Canon, Nike, Ford, Canada Goose, Lexmark, Spin Master and Roor, the pre-eminent German manufacturer of bongs.

Some of these brands only run into counterfeiting problems every few years, but Lipkus says he deals with anywhere between 500 and 650 cases every year. He pursues several avenues at once. He works with investigators (some employed by the brands themselves, some private) to ferret out counterfeit goods; serves and explains cease-and-desist letters to the people selling those goods; and, if that doesn't work, joins forces with police departments to crack down on the sellers. (He also helps train police officers in the recognition of counterfeit items.) As well, he launches civil lawsuits—for example, this past April, with Lipkus's help, Louis Vuitton sued several retailers in the Toronto area, including Dr. Flea's Flea Market, for knowingly or negligently allowing ersatz Louis Vuitton goods to be sold on their premises.

Over the course of his anti-counterfeiting career, Lipkus has served more than 10,000 court orders and cease-and-desist documents, and for the most part, he says, those offenders never offend again. But he has also received death threats and, in 2002, spent a month under police protection, unable to leave his house. "I believe I'm on the right side," he says. "And I feel good when I stop somebody and they never do it again. It's great job satisfaction. But my wife would tell you I'm the guy in the joke about the puddle of manure who's sitting there, shovelling and singing and going, 'I know there's a pony in here somewhere.'"

In the weeks leading up to the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver, Dale Ptycia looked out at fans in the city's stadiums and arenas, and saw a sea of fake Team Canada jerseys. For Hockey Canada's senior manager of licensing (and, not incidentally, the man who led the creation of the current Team Canada logo), the fakes were easy to spot: The Olympic rings on the phony jerseys were multicoloured; on the real ones, they were pale blue. They also had fight straps—a piece of fabric that attaches to a player's pants and prevents the jersey from being pulled over his head—a feature found only on limited-edition $500 "game jerseys." Ptycia and his colleagues estimate 90% of the jerseys they saw in the run-up to the Olympics were knock-offs.

Counterfeit Team Canada gear had been a scourge for years, entering the country through bulk shipments and container loads. But late in 2009, the counterfeiters changed their strategy: They began sending packages of jerseys—anywhere from one to 20 at a time—by regular mail. Canada Post became suspicious because all the parcels were bound for the same address in Vancouver, and the declared value of each jersey was just 10 bucks, though the real thing was retailing for many times that. Two weeks after the Olympics, the RCMP contacted Hockey Canada to say there were 16,000 suspected fakes stockpiled at a Vancouver mail depot. "I think we intercepted about a 10th of what came into the country," says Ptycia.

According to Ptycia, between 2008 and 2012, as much as 60% of Team Canada jerseys in the marketplace were counterfeit. With other sports brands—the NHL and NFL, especially—the percentage was even higher. The explosion of e-commerce and online resellers like eBay and AliExpress in China, as well as thousands of private websites, made the sale and distribution of counterfeits extraordinarily easy and nearly impossible to police. "It's almost like a Whac-a-Mole game," Ptycia says. "Sometimes you shut down one, two, three. But then the same group of people opens up another web shop. It's so easy to do and doesn't cost a lot—you register a domain name and away you go."

In 2005, the RCMP seized $7.7 million in counterfeits; by 2012, that number had climbed to $38 million. Two years later, trying to staunch this growing flow, the federal government passed the Combating Counterfeit Products Act, which allowed companies to work directly with the Canada Border Services Agency in identifying and detaining illegal goods. But with the CBSA's new powers in place, the RCMP took its eye off knock-offs. The actual amount of fake goods coming in didn't drop, but the detentions did—between 2015 and early 2017, CBSA-detained shipments reportedly added up to just $600,000 (though about half the shipments had no dollar value attached). Stuff was still getting in—a lot of stuff.

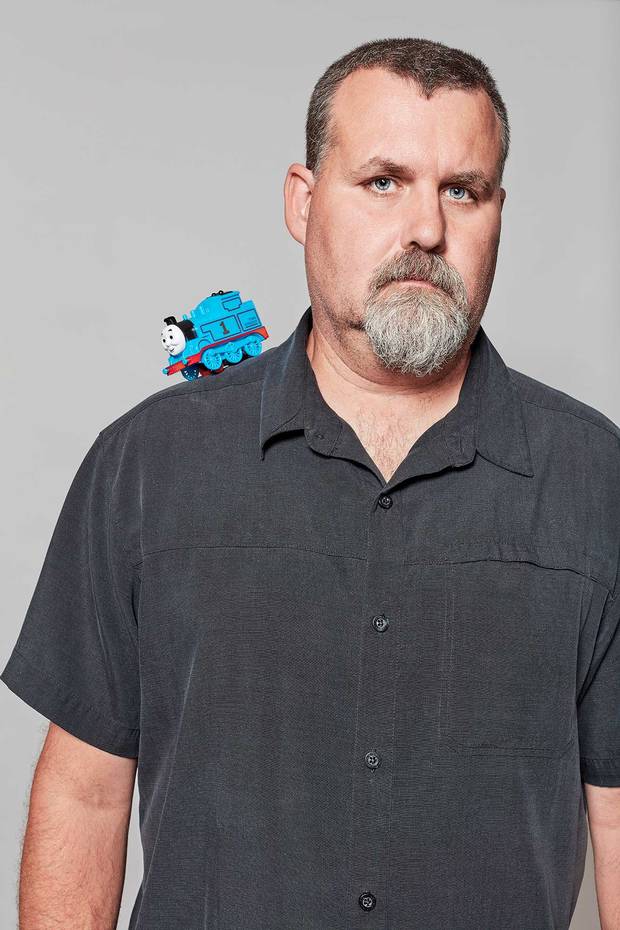

Toronto Police Detective Robert Whalen, Canada’s top anti-counterfeiting cop, busted an import-export operation late last year, confiscating $2.5 million in fake makeup and Thomas the Tank Engine toys

Chris Robinson/Fuze

Most of it is destined for the United States, where counterfeiting is taken far more seriously, and where business and law enforcement have more tools at hand to fight the flow. American border officials can seize and destroy counterfeit goods, whereas Canadian agents can only detain shipments (usually at the expense of the brands being counterfeited). Homeland Security can even shut down Internet domains if they're selling rip-offs. Terry Hunter, vice-chair of the Canadian Anti-Counterfeiting Network, works for the CSA Group, which helps develop standards for a number of industries, and provides testing, inspection and certification services. He gets four to six calls a week from American customs investigators to verify the legitimacy of CSA marks on shipments they've inspected. Between 80% and 90% of the time, they're finding counterfeits. In Canada, on the other hand, in the past eight years, he's received exactly one call. "The general public, law enforcement and our government really don't see the big picture when it comes to counterfeiting," he says, "and how it impacts public safety and our industry in Canada."

Canadian brands obviously lose money when consumers buy counterfeit versions of their goods. Legitimate retailers lose money when other, less scrupulous retailers sell counterfeit copies of the items they stock. Those products are also typically made in unregulated factories with lousy hygiene and safety conditions by overworked, underpaid (sometimes underage) labourers. "It's truly supply and demand, where the consumer doesn't want to pay fair market prices," Ptycia says. "But those fair market prices accurately reflect the specific needs of all the workers in the supply chain—who receive fair compensation and fair working conditions all the way through—and create jobs for Canadians, whether it's truckers, retailers or store clerks. If consumers skirt that, we obviously hurt part of our industry and our country's commercial activities."

Most Canadian brands take this issue very seriously. Canada Goose, for example, has dedicated an entire section of its website to the problem of counterfeits. But financial losses can be tricky to measure, and some brands, particularly luxury ones, don't aggressively combat counterfeiting because they believe they're not really losing sales—consumers buying fakes aren't going to lay out the cash for the real thing anyway. But when the market is flooded with fake Chanel purses, the real products start to lose their cachet and value too. Call it the counterfeit conundrum: Are you going to spend money on real Chanel when no one can tell if your Chanel is real? And in other cases, a brand can both lose sales and have its public image irrevocably damaged. When I spoke to Daryl Somes, the private investigator, in July, he was involved with a certain cellphone accessories brand that has been so thoroughly counterfeited, he and his fellow investigators could barely find an authentic model in the marketplace. "That's a problem, because they're losing all those sales," he says. "And the product is garbage, so they're losing their reputation. With a brand like that, they're almost in emergency mode."

But forget shopping. If you're considering a life of crime in Canada, you could do worse than to go into counterfeiting. Risk is low, profits high. Police departments don't really care (mostly), the courts can't be bothered (usually), the government's got other things to worry about (apparently). Detective Robert Whalen, of the Toronto Police Service's 55 Division, is considered the country's top cop when it comes to anti-counterfeiting—"He's one of the good guys," Somes says—and even he spends only eight or nine hours on it a month.

One reason is that the Toronto Police Service, understandably, has more important things to worry about: homicides, drugs, sexual assault. Resources are stretched, budgets forever being cut. But just as importantly, counterfeiting isn't something the courts have shown much interest in. The standard charges faced by a counterfeiter are fraud, possession of property obtained by crime, and "passing off wares"—that is, selling something as if it were something else. The potential fines and criminal penalties are rather severe. But what usually happens when Whalen brings a person to court—say, with evidence that they've imported half a dozen container loads of counterfeit toys, never tested to show they're safe for kids—is that person will enter a guilty plea for something under the trademark or copyright act to have the criminal sanctions withdrawn. And then, in order to free up court space, a judge will give a $500 or $1,000 fine—barely lunch money for an importer making, as Whalen claims, $100,000 a week. "Earlier in my career, I did a lot of organized crime work," he says. "And I've run into some drug dealers I dealt with many years ago who are now selling counterfeit property. They've told me they make the same amount of money, if not more, and if we arrest them, they get just a small fine and are back up and running the next day."

Whalen says one problem is that judges, like most people, don't think of or aren't aware of the magnitude of the counterfeiting problem. "Louis Vuitton is selling handbags for $7,000, $8,000," he says. "It's hard to convince someone that a person walking down the street selling a $10 Louis Vuitton bag is hurting Louis Vuitton." But counterfeiting, as Whalen's drug dealer example demonstrates, is not just damaging luxury brands. The majority of counterfeiters are or have links to organized crime: traditional Mafia, Asian gangs, biker gangs. And counterfeiting, with a money trail that's often difficult to trace, can finance other, more obviously sinister criminal activity, from human trafficking to arms sales to terrorism.The guns used in the Charlie Hebdo attack in 2015 were bought with money earned through the sale of fake Nike shoes on the streets of Paris.

Last December, Whalen helped bust a west Toronto importer-exporter who was selling fake makeup under Kylie Cosmetics, Urban Decay, Younique and other brands. Customers had started complaining the stuff was causing rashes. The rights holders hired private investigators to buy products undercover and reported to the police, who put the suspect—"a business and individual I had previous dealings with," says Whalen—under observation.

It took 20 officers two days to round up $2.5 million in counterfeit goods—not just makeup but also fake Thomas the Tank Engine toys, a Bluetooth headset that overheated and a Magic Bullet blender that smoked when turned on. One arrest is still before the courts, and the fake goods are taking up space in a police evidence locker; they will eventually be destroyed.

A selection of counterfeit products rounded up by Lipkus and Whalen (clockwise from top left): Kylie Cosmetics makeup that caused rashes; a pair of jeans that mixes two competing premium brands, Gucci and Louis Vuitton; a phony Beats by Dre Bluetooth speaker; and plush toys—a mashup of Disney’s Avengers and Universal’s Minions characters—with no “new material only” tags

Chris Robinson/Fuze

Even trying to protect the public from domestic danger is fraught. A lot of house fires, Whalen says, are believed to be caused by counterfeit electrical products. But this is almost impossible to verify, and therefore stop, because very few house fires are investigated by the police or fire marshal. "They really only investigate ones that are extremely high-dollar-value or where there's loss of life," he says. "So there are a lot of unsafe products that we're just not seeing."

But if Canadian courts and cops don't have the interest or resources to adequately take on counterfeiters, one retired Mountie in North Bay, Ontario, has become a very effective secret weapon. Using just a colour-coded Excel spreadsheet, Barry Elliott single-handedly runs the Canadian Anti-Fraud Centre's Project Chargeback and has figured out an ingenious way to choke off financing for counterfeiters at the source—their banks. The Anti-Fraud Centre (part of the RCMP) has long targeted merchant accounts to combat mail and phone fraud, but in 2010, after a couple of complaints about fake Canada Goose products, they started doing the same for counterfeit goods sold online. Elliott teamed up with the banks, and Visa and Mastercard, both of which now offer chargeback policies that guarantee purchases for between 120 days (Mastercard) and 540 days (Visa)—"You could buy a Canada Goose coat a year ago with your Visa," Elliott says, "and find out today it's counterfeit, and you'd get all your money back." He started tracking the websites and merchant account numbers of retailers that have sold counterfeit goods. Once a merchant account has issued a counterfeit chargeback, it's terminated. But too many of those, and the bank that issued the accounts gets fined by Visa and Mastercard. If the bank continues to misbehave, the companies can suspend the bank's credit card privileges.

Elliott traced almost 100% of these accounts back to four banks based in China. The fines levied have been high—more than $20 million to date—but so far, Elliott says, they haven't been enough of a deterrent. "It's just a cost of doing business for those guys," he says. "It's a unique situation, because organized crime in China is obviously linked to the banks, and there's corruption. But you have to look at the risks the banks are taking. They're the money guys for organized crime, but they don't want to get burned." Put simply, if a merchant account is terminated and chargebacks keep coming in, the account's assets will be quickly depleted. Once the account is empty, the bank has to pay the credit card companies back. And with Visa's 540-day policy, those chargebacks can come in for a long time. "They can get hit heavy and hard and quickly," Elliott says. "Online sales being the way they are, you can have a lot of activity in a hurry, and if the bank isn't watching what's going on, they can get caught with their pants down." Elliott's goal is to make it impossible for counterfeiters, and con artists of any stripe, to use credit cards as a payment method.

Canada was the first to adopt this strategy, and since then, Elliott has criss-crossed the globe, making presentations to government and law enforcement agencies in Italy, India, Switzerland and Russia. For the past year, the United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute has been analyzing different follow-the-money approaches to online counterfeiting, and project officer Elena D'Angelo says the chargeback program is one of the most effective. "It's focused on consumer protection," she says. "It can be applied worldwide, and because it's focused on the credit card companies, we don't need additional formal agreements.

And last but not least, it attacks criminal networks by depriving them of

their resources." While no other country has fully implemented the pro-

gram yet, in September, Elliott demonstrated it to 50 nations at the World Intellectual Property Organization in Geneva and will present it to APEC next year. "I call it the Happy Project," Elliott says. "Law enforcement's happy, the public's happy, the brands are happy, the banks are happy."

Elliott spends a lot of time helping victims of counterfeit fraud. But there are two types of victims he never reaches: those who are pleased with their cheap knock-offs and aren't complaining, and those who don't know they can call the number on the back of their credit card to request a refund. "It's a question of educating the public about their protection," he says.

Which is what Lipkus is focusing on as well, in his way. For almost two decades, Lipkus says he's held many meetings with attentive, concerned public officials. But not much has changed. So, in what spare time he has, Lipkus has taken his fight to the public, trying to change attitudes toward counterfeiting and piracy, especially among generations that have never known a world without online shopping. He visits universities, pro bono, to lecture students on counterfeiting, and he has volunteered with the Unreal Campaign, an international push to educate teenagers about intellectual property and the dangers of fakes. "Let's face it," he says. "We still have illicit drugs. We still have prostitution. We still have gambling. We're never going to eliminate crime, but if more people understand counterfeiting's a crime, they won't do it."

Sometimes his audience is even younger. A few years ago, one of Lipkus's former clerks, who had become a teacher, invited him to speak to her class of seven-year-olds. She'd previously brought in doctors and flight attendants and police officers, but she'd never invited a lawyer, because it was difficult to explain to children what exactly a lawyer does. Lipkus was different. He was, the teacher told her class, "the protector of toys."

So Lipkus went in and explained to the kids that real, safe stuffed animals all had tags sewn onto them that read "new material only." "What does it say?" he asked the class. "New material only!" they yelled back.

That night, Lipkus's firm got a call from the mother of one of the students. Her daughter had placed a dozen plush toys outside the door of her room, saying they were counterfeit and refusing to come out until they were removed from the house. The mother checked and, sure enough, none of the stuffies had "new material only" tags. And, sure enough, all the ones her daughter had kept did have the tags. The mother was irate—but not with Lipkus. There's something wrong with our system, she said, if my seven-year-old has to educate me on what's dangerous for her.

"But the kid got everything right," Lipkus says. "And if she can do it, believe me, we can do it."

When most people think of counterfeiting, they think of ersatz luxury goods like Calvin Klein underwear (or, in this case, “Calvin Klain”). Lawyer Lorne Lipkus warns that counterfeiting isn’t a victimless crime, however—it’s increasingly a safety issue too

Chris Robinson/Fuze