Mark Josephs of Kisko Products at his Woodbridge, Ont., plant.

Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

Forty years after his immigrant parents decided to launch a business in Ontario, Mark Josephs isn't in much of a mood to celebrate their success. Between new workplace legislation, soaring hydro costs and mounting fees for other government programs, he feels his family-owned enterprise is under attack.

"Our largest obstacle is this provincial government," he says. "They're absolutely killing us."

Mr. Josephs makes freezies, those neon-bright tubes of sugary ice designed to sweeten a kid's summer days. His family's company, Kisko Products Inc., employs about 80 full-time staff at its Woodbridge, Ont., plant as well as another 100 or so seasonal workers. As is the case for most mid-sized manufacturers, it occupies a narrow and unforgiving niche. On one side are a mob of Canadian and U.S. competitors eager to grab its business. On the other side are big retailers, such as Costco and Loblaw, that never stop pressing for lower prices.

The opposing forces don't leave Kisko with a lot of breathing room and the Ontario government is only adding to the squeeze on its profit. Mr. Josephs figures his electricity costs jumped by more than half between 2012 and 2016, from $178,000 a year to $277,000. On top of that, increased levies for the provincial blue-box program are poised to add at least another $70,000 a year in costs.

Related: Why does Ontario's electricity cost so much? A reality check

The cruellest blow, however, is the province's new workplace legislation, which will boost the minimum wage from $11.40 an hour to $15 an hour over the next 18 months while imposing a thumping new load of obligations on the Josephs and other employers. By the time the effects of the wage hike ripple through his work force, Mr. Josephs figures it will add another $600,000 to his annual costs.

As he totes up the added costs, his voice shakes. More than a quarter of his production already goes to the United States, and despite having sunk millions of dollars into his Woodbridge location, he is asking his chief financial officer to price several U.S. states to see whether it might make sense to relocate manufacturing operations there, while turning the current factory into a warehouse that would employ only a handful of people.

A move would not be his first choice, but "we're being hammered with things that make us uncompetitive," Mr. Josephs said. The provincial government loves to brag about attracting units of U.S. tech giants such as Google, he says, but it shows little interest in listening to the small and mid-sized businesses already established in the province.

"I'm so frustrated because I feel like I'm fighting an enemy that I can't win against because they have all the power in the world," he says. "I keep asking, 'How do I get out of this place?'"

A worker inspects product at the Kisko plant in Woodbridge, Ont.

Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

The controversy

Ontario's competitiveness, or lack thereof, is a matter of more than parochial interest. As Canada's most populous province and still the country's heavyweight in terms of economic output, Ontario's ups and downs carry implications for the entire country. Right now, those implications can be read in two very different and contradictory ways.

The top-line numbers indicate an economy that is humming along. As Premier Kathleen Wynne's government will tell anyone who cares to listen, Ontario outpaced all G7 countries in terms of GDP growth in 2016. It is on track to balance its budget in 2017 for the first time since the 2008-09 global recession while its unemployment rate has sunk to 6.5 per cent, the lowest in a decade.

Dig a bit deeper, however, and Ontario's apparent boom looks shaky. The province's Panel on Economic Growth and Prosperity has long tracked what it calls the province's "prosperity gap." This is the difference between the amount of economic value Ontario generates per person compared with how much is produced by folks in 10 similar jurisdictions, including countries such as Australia and the Netherlands, U.S. states such as Michigan and Tennessee, as well as Canadian provinces such as British Columbia and Quebec.

According to the panel, the typical Ontario resident produces $2,740 a year less than the median person in those other jurisdictions. The size of the gap is even more disturbing than it appears because Ontario is putting forward a greater "work effort" than its peers – in other words, it's working more hours per capita. That reflects the fact that Ontario has more working-age people as a fraction of its total population than most of those other countries and regions.

Yet despite the province's relative youth, Ontario doesn't seem to be reaping much of an economic advantage. In fact, "all three international regions and five U.S. states [that Ontario is benchmarked against] have higher levels of prosperity, and most of their economies are growing faster than Ontario's," the prosperity panel found.

The message is unmistakable: When supposedly forgotten rust-belt states such as Ohio and Indiana – home to millions of disgruntled Donald Trump supporters – are leaving Ontario in the dust, there is reason for Canadians to worry about the future of the country's economic heartland.

There's even more cause for concern if you shed a light on the foundations of the provincial economy. Much of Ontario's current prosperity, such as it is, rests on a squishy base of airy, debt-inflated real estate prices.

As home values in Toronto and nearby areas have soared in recent years, the real estate services and residential construction sector have become the biggest single drivers of the Ontario economy, according to the Institute for Competitiveness and Prosperity (ICP), a non-partisan think tank. By comparison, other industries, such as finance, wholesale trade and manufacturing, have lagged far behind. A reversal in the housing sector would spell trouble for the provincial economy, the institute warns.

So what can be done to stabilize the province's outlook and boost its long-term prospects? The most powerful medicine would be policies that could help improve the province's abysmally low productivity – in other words, how much output it generates for every hour of labour. If Ontario could simply boost its productivity to the median level of its peers, its $2,740 per person annual shortfall in output would flip to a $4,710 per person advantage, according to the ICP.

That sounds eminently doable – except that nobody is quite sure why productivity is so low. There are, broadly speaking, two theories and they're diametrically opposed.

One view, held by Mr. Josephs and many other mid-sized employers, blames a provincial government that seems more concerned with waging social-justice battles than encouraging entrepreneurs. They say a flood of business-bashing policy has created an environment in which companies are reluctant to invest in productivity-enhancing improvements.

The other view, common in policy wonk circles, says the province and the country have done most of what is necessary to encourage private enterprise. Adherents of this viewpoint point the finger at the private sector for not taking advantage of the opportunities.

Both sides deserve a close hearing.

The booster's case

Optimists about Ontario's future argue that critics are exaggerating its problems. Consider, for instance, the province's energy policy, which even boosters will admit has been a shambolic mess in recent years. A desire to encourage green energy resulted in a doubling of electricity rates between 2006 and 2015. Power now costs more in Ontario than in any of the top-10 auto-producing regions of the United States. Here's the thing though: While rates have shot up, the current difference between Ontario and competing jurisdictions in the United States is not as large as commonly believed, at least for large manufacturers.

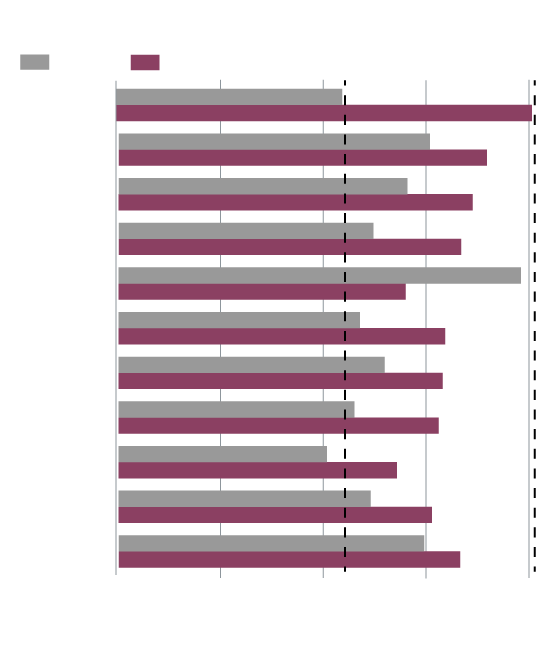

Electricity prices per kWh in U.S. dollars

2006

2015

Ontario

Michigan

Ohio

Indiana

Texas

Illinois

Tennessee

Missouri

Kentucky

Alabama

Mississippi

0.06

0.08

0.00

0.02

0.04

john sopinski/the globe and mail

sources: Automotive Policy Research Centre

Electricity prices per kWh in U.S. dollars

2006

2015

Ontario

Michigan

Ohio

Indiana

Texas

Illinois

Tennessee

Missouri

Kentucky

Alabama

Mississippi

0.06

0.08

0.00

0.02

0.04

$0.10

john sopinski/the globe and mail

sources: Automotive Policy Research Centre

Electricity prices per kWh in U.S. dollars

2006

2015

Ontario

Michigan

Ohio

Indiana

Texas

Illinois

Tennessee

Missouri

Kentucky

Alabama

Mississippi

0.06

0.08

0.00

0.02

0.04

$0.10

john sopinski/the globe and mail, sources: Automotive Policy Research Centre

A recent report by Greig Mordue and Kelly White of the Automotive Policy Research Centre estimates that an auto assembler will pay a premium of roughly $18 (U.S.) a vehicle in extra power costs to assemble a car in Ontario rather than in the least expensive U.S. jurisdiction. In the context of a $30,000 vehicle, the difference is meaningless.

"Our research indicates that even though [electricity] rates have been described as a major cause of the deteriorating competitiveness of Ontario's manufacturing industry, the size of the gap is not currently large enough to warrant such characterizations," the researchers write.

While electricity rates aren't quite the disadvantage they're often made out to be, Canada's hypercompetitive tax rates turn out to be a surprisingly powerful advantage. Marginal corporate-tax rates – that is, the effective rate of tax that would be payable on new investments – are nearly seven percentage points lower in Canada than in the United States, according to a recent analysis by Fred O'Riordan and Jack Mintz of Ernst & Young LLP. Even if some flavour of Trumpian tax reform were to be adopted by the U.S. Congress – and that's far from a sure thing given current political battles – Canadian tax rates would still be competitive.

"I would be more bullish than bearish about Ontario, all things considered," Mr. O'Riordan says.

He's not the only person to speak this way. Few people know Ontario's competitive position as well as Don Drummond.

After holding senior positions in the federal Finance Department, he served as chief economist at TD Bank before chairing a hard-hitting commission on closing Ontario's gaping fiscal deficit. Today, he teaches at Queen's University in Kingston and continues to be a leading voice in policy debates.

He doesn't understand why parts of the private sector are so down on the province's prospects.

"I get the minimum wage concerns, especially the steepness of the increase, and I understand the concern over the runup in electricity prices, but really, fundamentally, why would you think that government is ruining your business?" Mr. Drummond said.

He ticks off a list of the province's strengths: abundant natural resources, easy access to key markets in North America and Europe, a diversified work force, good universities and a wonderful pool of skilled labour – "better than anywhere in the United States."

The provincial government, he argues, has been more diligent than critics will admit. His commission laid out more than 350 recommendations back in 2012 and the majority of them have been implemented. His group's overriding objective was to recommend a regimen to balance the province's budget by 2017 and Ontario appears to be hitting that target right on schedule. "So, all things considered, on the fiscal front, I have to say, well done."

For Mr. Drummond, the fascinating question is why businesses have not invested more in their enterprises to boost productivity and take aim at global markets.

Back in the 1980s, he firmly believed that Canada's miserable record on productivity was the result of bad macroeconomic policies, ranging from counterproductive tariff barriers to high taxes.

"But, lo and behold, I would say that if I had set out a wish list 30 years ago [to boost competitiveness], about 70 per cent of it got done," he says.

The mystery is why Canada continues to be a woeful performer in the productivity sweepstakes despite vastly improved public policies. The most sweeping, if rather vague, explanation for its lagging performance is that Canadian leaders – and particularly those in Ontario – lack the appetite to invest in the future and reach for something more.

"Ambition seems to be the thing we're missing," he says. "It's missing on the part of government and it's missing on the part of the private sector."

The factory owner's view

Don't lecture Jocelyn Bamford about lack of ambition. She helps run Automatic Coating Ltd., a company founded by her husband's family in the 1950s. It started out repairing washing machines in a garage.

Today it employs 75 people in a 70,000-square-foot factory in Scarborough, Ont., and specializes in advanced technologies for coating tanks, pipes and other industrial equipment.

"We are absolutely losing our competitiveness," Ms. Bamford said.

The culprit, she said, is a provincial government that has rained blows on small and mid-sized businesses over the past two years. The unwelcome changes include unpredictable energy costs, a complicated cap-and-trade system for greenhouse-gas emitters, the planned hike in the minimum wage and new rules that will make it far easier for organizers to unionize workplaces.

"It's all happened in a short period of time," she says. "Small manufacturers don't have government affairs people or lobbyists. Most of us keep our heads down and focus on running our business. But we do feel we're under attack."

This past August she launched the Coalition of Concerned Manufacturers of Ontario to help plead the sector's case to provincial government. It now spans more than 80 small and medium-sized companies that collectively employ more than 3,000 people.

Right now, she says, the only factor that allows many of the province's manufacturers to compete against U.S. rivals is the low Canadian dollar. But she worries about the impact of the new workplace legislation, especially the radical hike to the minimum wage.

The problem, she says, is that a higher minimum wage forces up wages across the entire pay scale. Experienced workers who are already making $15 an hour will demand a few dollars more, and the ripple effect will result in dramatically higher labour costs over all.

What are her alternatives? She and her husband have debated whether it makes sense to cut jobs and automate more of their factory operations. Even simpler, though, would be a move to Mississippi, where the state is dangling a tempting package of relocation benefits.

Automatic Coating could save $93,000 to $379,000 a year by moving its operations there, according to an analysis performed by a group of Queen's University business students.

The relocation would also go down well with the U.S. Navy, one of the company's largest customers. It currently ships hatches and other parts to Ontario for the company's patented coating process but it would welcome being able to get the work done on American soil.

The biggest reasons to keep Automatic Coating in Ontario, Ms. Bamford says, are loyalty to existing employees and some purely personal considerations. For instance, her three children are all avid hockey players and would not have nearly the same opportunities to play the sport in the southern United States.

Other than that, she sees few other advantages to remaining in Canada. When she is told that policy experts such as Mr. Drummond tend to have a more positive view of the province's appeal, she snorts.

"You can tell Don Drummond," she says, "that the only things Ontario has going for it right now are the exchange rate and hockey."

Who wins?

The debate over Ontario's competitiveness is really an argument over the shape of tomorrow's economy. The province's policymakers clearly lean in the direction of a future in which largely green sources of energy power an economy populated by well paid, unionized workers.

From the perspective of a business owner, that vision means higher energy costs, bigger labour bills, more workplace bureaucracy. The clashing positions would ordinarily play out over many years, but the governing provincial Liberals are pushing their agenda ahead with unusual speed – perhaps an indication of their uncertain political outlook and need to appeal to core voters.

If there is one thing that is beyond dispute in the current situation, it's that the sheer velocity of change has antagonized many parties.

For instance, the move to a $14-an-hour minimum wage by 2018 and $15-an-hour by 2019 is by far the biggest, fastest increase in the province's history, according to the ICP. The hike – which works out to an increase of 32 per cent in 18 months – could result in job cuts in sectors, such as retail, restaurants and hospitality services, that employ many minimum wage workers and don't have time to react.

"But all that being said, I don't think the $15 minimum is likely to be a game changer in the long run," says Craig Alexander, chief economist of the Conference Board of Canada, a not-for-profit research organization.

He notes that several U.S. states have announced their own plans to move to similar wage levels over the next few years. Rather than relocating operations, many employers in Ontario are likely to respond to higher wages by reducing jobs and installing more automation.

"You already see the trend at some fast-food restaurants, where you order at a screen instead of talking to a human," Mr. Alexander says.

His analysis demonstrates the complexity of any policy change: By encouraging automation, higher minimum wages could boost productivity over the long run, which the province badly needs. But in the short run, a higher minimum wage could result in fewer jobs or, at least, fewer new jobs.

In a fine example of unintended consequences, the province's efforts to create a worker's paradise may wind up hurting less-educated, marginal employees, who would be most prone to being replaced by machines.

Mr. Josephs, the freezie maker, acknowledges the many conflicting factors. It's difficult to find anyone who will work for minimum wage these days, he says. His big worry is not so much the hike itself but the knock-on effect it will have on workers who may be making slightly more than the $15-an-hour level and will want raises of their own.

If he decides to stay in Ontario, he's looking at automating his plant to drastically reduce his use of seasonal workers, slashing the number of hires from 100 to about 40. "And we'll be looking to reduce even further," he says.