I tried my very best to be calm, convincing myself that everything before this, all the agony and the ecstasy in my life, had been preparation for this moment.

In the hospital waiting for our daughter's birth, my husband and I cycled through sitting and standing at the end of our surrogate's bed. Labour was induced at 11:30 p.m., and through the dead of the night we watched a team of nurses, a midwife and a doctor check the progress, trying hard not to interfere, but also wondering what every update meant, because this was our first child.

I felt a particular burden. As part of our birth plan, we'd collectively decided that after the baby's umbilical cord got cut, she would rest on me – the way a newborn normally would on a mother's chest. The heartbeat she'd hear would be mine.

Under the night's tranquil darkness, a piece of advice I'd once heard floated back into my consciousness: that a kid's demeanour tends to resemble its parents'. Remembering that, I wanted to be calm for my new daughter, Eva, when she was first handed to me, helping her feed off my emotional stability.

It was a stretch to get there. I could remember holding exactly one baby – my nephew, a few times – before this moment. I'd never even changed a diaper. Being a dad was foreign territory.

This would be a sudden adjustment. Eva always felt very much like our child, and I went to nearly every doctor's appointment during the pregnancy, but she wasn't part of our everyday lives the way she was for our surrogate. Neither Matt nor I got tired from carrying her, and neither of us had to deal with the health issues that come with pregnancy, or the hormonal swings.

But then, after only a few hours of labour, she emerged. Needing me. Needing us.

The midwife placed her on my bare chest and a natural instinct took over. Time slowed. For those 20 minutes when she nuzzled into me, I felt like I was made for this.

The serenity was short-lived. Serving as Eva's primary caregiver in the chaotic year since, I was exposed to a realm most men never see. The experience was so earth shattering that my worldview is permanently altered.

Some realizations came quickly, and will be appreciated by any new parent. After the initial adrenaline rush ebbed, I started to grasp just how precious sleep had become. Eva arrived at 5:01 a.m., the morning after a snowfall, and there was no time to make up for the all-nighter we'd just pulled. There wouldn't be for months.

Other, deeper issues presented themselves as more time passed. Over 10 months of paternity leave, I discovered that being a primary caregiver is often an onerous, thankless task. It is the bedrock of our society, allowing the world as we know it to function, but the job's value, and its complexity, is largely invisible to those who haven't been immersed in it.

I started to feel a deep connection with other women, particularly my mum – something rooted in a sense of shared experience, as if we fought the war together, and hardly anyone else knew what the trenches were like.

The more distance I get from those chaotic first months, the more epiphanies I have. Eva turned one year old this week, and I understand, now, just how lucky Matt and I are to even have a child, and I've grown ever more grateful to the women who participated in her creation. I've also learned the power of social norms, having personally experienced how painful it is to free yourself from gendered roles – or the expectation that a man does this, a woman does that. This socialization toys with you no matter your sexual orientation, or how open-minded you are.

And I've realized that even in a supposedly progressive country such as ours, we truly do not value what it takes to raise a child, no matter the sex of the parent.

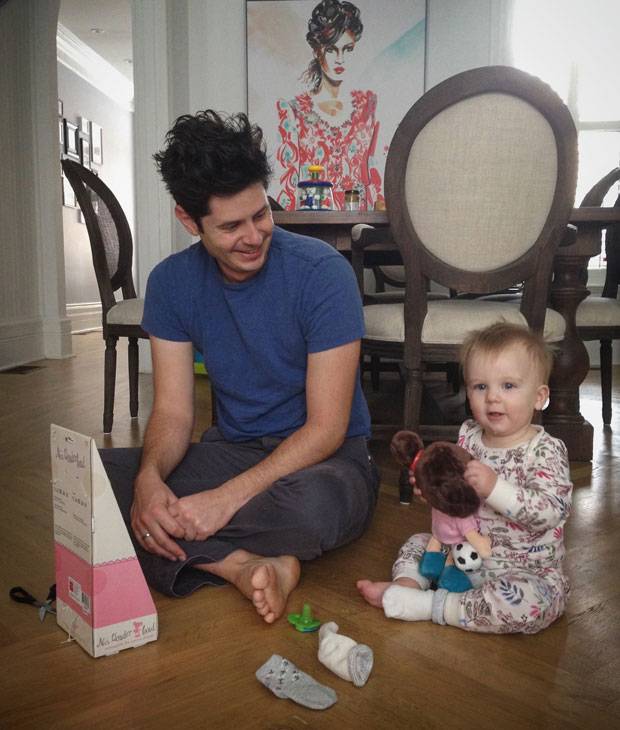

Eva, Year One: Scenes from the new family’s life include Eva’s trip home from the hospital, top left, trips to San Francisco and Lake Louise, and many moments in between.

This journey began a little more than three years ago, starting with our struggle to conceive as a gay couple. Surrogacy is well known, but it's still a grey area in Canada – it isn't illegal, but it isn't fully legal, either. All the steps are siloed, for legal protection, and prospective parents must figure out how to connect the dots themselves.

It all felt very daunting, a silent battle we endured in private before Eva was even born. Hardly anyone knew how many hurdles we had to clear – drafting legal contracts, creating embryos, social-worker screenings – or how much mental energy it consumed.

The first major step was to find an egg donor. Using the surrogate's own eggs is not advised because, under Canadian law, she'd have more right to claim the child should she try.

Settling on the donor is, quite possibly, the marital negotiation most fraught with risk. And it is arguably the most important. It is the donor's genes our child would share – not the surrogate's. The best piece of advice provided to us, by our beloved lawyer, was to choose someone that resembled the friends we cherish most, not the profile with the pictures best suited for a dating app.

Matt and I spent a weekend each scouring a donor agency's database. In the end, I chose five profiles I'd be happy to explore; Matt chose only one. By some divine intervention, that one profile was in my five.

We ended up with roughly 20 of the donor's eggs. Matt and I divided them equally between us, inseminated them, then waited to see how many survived after five days before freezing them. In the end, three of mine remained, and four of Matt's.

Then we waited, and prayed that a surrogate would choose us.

We got lucky seven months later. While I was at a working lunch, our agency, Canadian Surrogacy Options (CSO), e-mailed to say there was a match. Ayesha had everything we were looking for: She was married, which meant her family wasn't solely dependent on her income should she need bed rest; she had five of her own kids and had been a surrogate before; and she was a nurse.

The agency told us to send her an e-mail, suggesting we "ask about the weather, her children, her job, then get into things like why she wants to do this again." I handled the correspondence because I'm the social butterfly in our marriage, and Ayesha and I e-mailed back and forth for a few weeks. Eventually, the three of us met for lunch at a Jack Astor's in the Toronto suburbs.

We clicked. Which was crucial, because in Canada, surrogacy is mostly a charitable act. (It's more of a business in the United States.) Scores of people have asked me how much Ayesha got paid for helping us, with an underlying suggestion that she must be a gold digger. Yet, under an informal Canadian rule, the majority of surrogacy expenses, everything from maternity clothes to cell phone bills – because they need a way to talk to the intended parents – can only be reimbursed up to $25,000.

Surrogates, meanwhile, must take a number of drugs daily, including injections of progesterone, to simulate the conditions of being naturally pregnant, as well as vaginal suppositories of the same hormone for the first three months – all while bearing the risks that come with any pregnancy, usually for a couple they just met. If anyone's money-hungry, it's the IVF clinics. Their costs are astronomical, and they're mostly kept unchecked by any regulators or governments.

The three of us committed to each other. Three months later, we transferred some embryos into Ayesha, watching them fly like shooting stars on the ultrasound screen.

A few days after the procedure, Ayesha texted me while I getting ready for work. She'd done an over-the-counter pregnancy test, and she sent me a pic that showed two faint, but noticeable, pink lines. I sat on the edge of my bed, half-dressed, grinning.

From our first meeting with CSO to Eva's birth, the whole process took 26 months. The worst part was waiting for a surrogate, because you have no control, but in hindsight it proved to be a bit of a blessing, giving us time to think through most of the crucial issues. Whose sperm would we use? (We transferred one embryo each.) Whose last name would the baby get? (We compromised: If she had my genes, she'd get Matt's last name, and vice versa.) Would we stay friends with the surrogate after the birth? (We hoped to, and we have.)

Tim and Matt’s wedding day. The two met as investment bankers on Bay Street, the home of a traditionally male-dominated finance industry where taking parental leave and putting personal life before work still carries a stigma.

Matt and I first met on Bay Street as junior investment bankers. While I left to become a reporter, he stayed. These roots proved to be both a gift and a curse.

Had Matt changed industries, we probably couldn't have afforded the costly surrogacy process. But it had its disadvantages, too. Finance is traditionally one of the most male-dominated industries and the common expectation is that a wife or a nanny will handle child-rearing issues – which may be one of the reasons why women fill only 13 per cent of the executive roles at Canada's six largest investment banks. The sector also breeds a culture that expects employees to work long hours and prioritize the client, or the quarterly profit, over personal lives.

And yet, I told Matt early in our relationship that I wouldn't be the proverbial banker's wife – meaning I wasn't willing to be saddled with all of the family and house duties while he focused on work. He and I are both type-A professionals, and a good story matters just as much to me as advising on a major merger or acquisition.

Then reality hit. Initially, we had talked about splitting parental leave in some fashion. But the closer we got to Eva's birth, the more hesitant he became. I started to argue that he was acting scared, and suggested he take some time off, if only to stand with the women he works with; he said he was just being practical because of our incomes.

In the end I took the sole leave – 10 months in total. Looking back on those early discussions, I'd say we were both a little unfair to each other. I ended up enjoying a longer leave, especially because the first few months are so brutal, and his hesitancy wasn't personal; it stemmed from a stigma that still runs rampant in the corporate world.

Right before Eva was born, I had lunch with a source who worked on Bay Street. He congratulated me for the pregnancy, then asked if I was taking time off. I said yes, then he replied: "If I took leave, it'd have to be in January, because I know they'd find a way to screw me." Translation: His bank's bonuses get paid in December, and taking leave in January meant he'd still be in the office, showing face, during the months when annual compensation was negotiated. In other words, he'd stay top of mind to his bosses.

The stigma spreads far beyond Bay Street. A friend works in sales for a large, reputable company, and one day he texted me to ask if The Globe had any issue with me taking a substantial chunk of time off. It didn't, at all, but I asked why he was inquiring. He said pat leave wouldn't even be thinkable at his shop. Intrigued, I ran this by another friend who works in a different industry. He said the same. His reasoning: "It's auto manufacturing, man." Even bringing the issue up could hurt your career. In 2018.

I've been back at work for two months and it's pretty clear the sacrifices won't be confined to pat leave. Already, it feels nearly impossible for both me and Matt to work at full tilt. In her first four weeks at daycare, I received three calls to pick Eva up mid-day because she had a fever – and the rules dictate she can't go back for 24 hours after each episode. The first two times, I was the one who worked from home the next day, handling some major breaking news while Eva munched on Mum-mums beside me. I was set to do the third, too, but a sympathetic friend stepped in and suggested to Matt that I was probably ready to lose it. (I was.)

In her essay, Why Women Still Can't Have It All, which went viral a few years ago, Anne-Marie Slaughter, a tenured professor at Princeton who took a top foreign-policy job in the State Department under Hillary Clinton, said it best: There is something about skipping out of work early for a kid, or even stepping away from your career, that is seen as "soft," or inferior, to the rigours of a professional job. There remains an unspoken hierarchy for personal worth, and family duties rarely top those from the workplace.

Before Eva was born, I was already sympathetic to her argument. My mum was a professional woman and had been the breadwinner in our family. Even then, I hardly had any idea of just how little society values child rearing, and how exhausting it is.

About a month after Eva was born, she wailed for three consecutive hours one afternoon. By 6 p.m., I had to put her on the floor beside me, while I lay on my back with my arms spreads out, like Jesus on the cross, repeating to myself, "I surrender." This from someone who graduated on the dean's list at McGill and earned a graduate degree from an Ivy League university, achievements that signify resolve in the upper echelons of business.

Last August, a Google engineer named James Damore, who had studied at Harvard University, circulated a memo to his colleagues that cited studies suggesting women score higher on neuroticism, which means they can't handle stress and are therefore less likely to become successful leaders. He was fired, and ridiculed, but he hasn't seemed to change his mind. I suggest Mr. Damore try being at home with a raging newborn.

Yet in my own way, I've helped shape this narrative. As a business reporter, I've written scores of stories and profiles about business leaders and politicians, most of which have focused on men, because they still dominate executive ranks and boards of directors. I used to be fascinated by how they rose through their careers. I still am. But now, I'm equally interested in how much support they provide to the spouses, nannies and daycare workers around them, none of whom get the glory.

Taking time away from work to be with Eva ‘proved to be one of the best things I’ve done,’ Tim writes,’ not just for my family, but for my career.’

Putting a public spotlight on these issues is bound to help, but it will likely take millions of smaller conversations – amongst friends, in the workplace, at home – for society to evolve.

What's been eye-opening for me is that they rarely happen. At least not with men. Many parents, and particularly moms, in my experience, are reluctant to talk openly about their hardships.

A personal example: At our first ultrasound, Matt and I saw two bright lights on the screen, which meant both of our embryos had caught. It was the perfect scenario – twins, one from each father. A few weeks later, Ayesha texted early in the morning to say she had some bleeding. She went in for a screen later that day, and while Matt and I sat in the waiting room of the IVF clinic, she messaged me to say there was only one heartbeat.

After the appointment, the three of us split up, and Matt and I both went back to work; we'd made plans to meet up at 4 p.m. for my mum's retirement party that evening. As I was leaving for it, he e-mailed to ask it if was okay if he passed on the event. He was tearing up in his office.

I often share this story, and when I tell women, they sometimes blurt out, "I lost one, too." As if there hadn't been permission to talk about a miscarriage with me, a man, until I brought it up. It's happened so many times, including with close friends, that I started to wonder how many of these stories we never hear.

I came to believe some of this reticence is socialized, possibly by small slights over so many years, all of which send subliminal signals about what makes a "good" mom and what men will tolerate. Early on, Eva had an almost unfathomable diaper rash, and about six maddening weeks into it, she and I had a mid-day appointment with a pediatrics specialist. While I was in the examination room waiting for the doctor, a nurse walked in and asked me if the mom was coming. I explained the surrogacy situation, and she said that made sense, because "Moms usually come to these." I was so tired, and so flustered, that I barely spoke up. But I wish I'd said, "What if Mom had a board meeting?"

I make it a point now to be candid, especially about how I struggled. Because I did, and my body showed it. My circadian rhythms were shot and my face broke out with acne. When I was on leave, I started seeing a pattern when chatting with women, especially mothers: We'd often small talk for a bit, then once I got frank, the floodgates flew open. It even happened with my own sister, with whom I'm rather tight. One morning, after a rather exhausting night, I texted her to vent because she'd been through this with my nephew. She replied: "I used to scream into the dark." I'd never heard her say that before.

As it stands, money and power often accumulate to those who aren't saddled with these duties, and who aren't burdened by the emotional stress they create. Speaking candidly should start to change the way we work, which is in serious need of a fix.

There are now more seniors in Canada than there are people entering the work force, which means we will need younger people to stay employed as the baby boomers retire, so that the economy grows and offsets the budget effects of soaring health-care costs and the like. But at the moment, it still feels like a struggle for both parents to engage in work they find meaningful.

The federal government has tried to make life easier for parents, by boosting child benefits for many families and extending parental leave to 18 months. These approaches serve a purpose, but I happen to believe real change comes from shared experiences.

I've come to support the Swedish model for parental leave. There, the government offers fathers money to take time off; if they don't go on leave, men forfeit the free money and the mother can't take their time in lieu. In economics, this is known as a "nudge," and this year's recipient for the Nobel Prize won for studying this very phenomenon. A little nudge, often a financial incentive, can cascade into huge systemic benefits.

I'm convinced that giving more men a taste of just how tricky raising children can be would not only help women advance in the workplace, but also provide more appreciation for different forms of care-giving, professions such as teaching and nursing and hospice work, where women predominate. Friends of mine work with autistic children and I'm horrified to hear how little aides in this line of work can get paid. Meanwhile, a man who manages underperforming mutual funds can still make boatloads.

For the men who need a little coaxing to take leave, I promise it proved to be one of the best things I've done, not just for my family, but for my career. I hope to do it again. The journey was a reminder that none of us are the centre of the world, and that stepping away doesn't mean you disappear; actually, it gives you time to flex a different muscle and return to work even stronger.

Sadly, the past year was also a harsh lesson in how much we still must evolve to accommodate parents – of either sex. The honest truth is that, when it comes to valuing family matters, we're still decades behind – and we shouldn't have to wait for change.

A PARENT'S LIFE: MORE FROM THE GLOBE AND MAIL