Auschwitz, 1945: A group of Jewish children in adult prison clothes are shown at the infamous concentration camp in Nazi-occupied Poland, then newly liberated by the Soviets. A few months after the liberation, the Red Army made a film with Polish extras about the liberation of the concentration camps, from which this image could possibly come.SZ Photo / Bridgeman Images

Erna Paris is the author of several books, including Long Shadows: Truth, Lies and History. This essay is adapted from a speech she delivered at Yorkminster Park Baptist Church, Toronto, in November, 2019.

Historical traumas seem to have their own timelines – and they are long. Think for a moment about slavery in the United States, an era that formally ended in 1865, but continues to wreak havoc in American civic and political life under many guises. Think about our slowly emerging knowledge of the Armenian genocide. It took place a century ago, yet the scale and the enduring import of the assault remains unacknowledged by the perpetrators, the Turkish state.

Persecution, with its attendant human suffering, is always a messy business: It burrows deep into consciousness and encompasses a range of extreme human emotions: from despair to rage, from guilt to denial. Sometimes, although more rarely, it even includes remorse.

And so it is with the Holocaust – an historically unprecedented assault against an entire ethnic group: the Jews of Europe. The Holocaust, a name that came into popular usage only in the 1970s, was unprecedented precisely because nothing on this scale had happened before. And because of the means employed: the deadly technology exploited by the Nazis to effect their murderous plan.

This month, we mark the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, the largest and most infamous of the Nazi’s death camps. It will no doubt be a time of sombre reflection and analysis – and a pointer to whatever trends may be emerging with regard to Holocaust memory. For the world’s reaction to this seminal 20th-century event has been evolving from the very start. And it has been fraught with controversy.

Looking back over the more than seven decades that have elapsed since the Second World War ended in May, 1945, I believe it is possible to identify stages in the way both the international community, and particular countries, have remembered – or chosen not to remember – the event we call the Holocaust. They are, first, muteness, or denial; second, acknowledgement – the current state of memory; and third? Well, we are in the realm of speculation, but we can identify trends.

Nuremberg, 1946: Nazi criminals attend a tribunal formed by British, U.S., Russian and French forces to hold them accountable.STRINGER/STRINGER/AFP/Getty Images

In the immediate aftermath of the war, when initial shock prevailed, far-reaching initiatives created a new international legal order. The United Nations was established in the hope of preserving peace. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the first signpost document of its kind in history, was a direct outcome of the genocide. So was the Nuremberg Tribunal, in which the top Nazis were tried for crimes against humanity by the victorious Allies – for there had never been such a court.

Some people believe that Nuremberg was one of the most important events of the 20th century. There are many reasons for this. First, because Nuremberg prosecuted major war criminals – and because, for the first time in history, it defined, and gave name to, the horrific crimes they had perpetrated. Second, because it prosecuted them fairly, according to due process. Third, because the courtroom testimony created a written record of Nazi atrocities. And fourth, because a half-century later, Nuremberg led to the creation of the International Criminal Court, the world’s first permanent independent tribunal to prosecute individuals for war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide.

Creating a new liberal world order in the immediate aftermath of the war set the stage for a period of international co-operation that has lasted the better part of a century, although it may be currently under threat. However, in terms of memory, the new institutions, enhanced global co-operation and the testimony recorded at Nuremberg did not mean that the horrific events of the Holocaust found public voice.

For at least 20 years after the war – until the late 1960s and even into the 1970s – there was little, if any, public talk about what had happened to the Jews. It was a silence that included many of the survivors, who remained mute out of shock and trauma. In Europe, especially in the perpetrator and collaborator countries of Germany, France and Hungary, for example, there was also silence, or minimizing, or outright denial.

Natzweiler-Struthof was the only concentration camp established by the Nazis in occupied France.Anne Ackermann/The Globe and Mail/The Globe and Mail

It was my own personal experience with this initial silence that drove me to the explorations of historical memory that have underpinned my writing life. During a student year in France in the early 1960s, I accidentally stumbled across the only death camp the Nazis had established in that country – a place called Natzweiler-Struthof, in the Vosges mountains of Alsace.

I was on a carefree weekend trip with a few young friends. We saw a sign for a “camp” and thought it might be fun to visit. I thought it might be something like the children’s summer camps I had attended in Northern Ontario. The place was empty, except for an indifferent caretaker who showed us the gas chamber, the crematoria and the dissection table.

I knew almost nothing about such things, and the shock I experienced led me to urgent questions. For example, I did not understand why I heard neither public nor private conversation in France about the fate of the Jews: After all, we were only 15 years or so away from these events. I also did not understand why I had learned so little growing up in Canada.

Many years later, I wrote about the trauma of this encounter and submitted my story to a small Jewish publication in Toronto. The editor sent it back with a little hand-scribbled note. No one is interested in these things, he informed me.

I would later discover that this early phase of Holocaust memory – or rather, forgetfulness – had its own trajectory in both France and Germany. So let me outline briefly what happened to Holocaust remembrance in each of these countries as a primer, of sorts, for how repressed historical memory evolves.

French President Emmanuel Macron lays a wreath on Jan. 23 at the 5th World Holocaust Forum at Yad Vashem Holocaust memorial museum in Jerusalem.Pool/Haim Tzach - Pool/Getty Images

A wreath of flowers lies at the Shoah memorial in Paris. France was occupied by the Nazis for four years during the Second World War.FRANCOIS MORI/FRANCOIS MORI/POOL/AFP via Getty Images

From late June, 1940, France was occupied by the Nazis and governed at Vichy, in the country’s central region, by General Philippe Pétain, a hero of the First World War. Gen. Pétain was adored by a majority of the French, and the collaboration of his government with the Nazis, including French police actions against Jews, was broadly accepted as a tool of national protection.

Yes, there was resistance to the Nazis during the Vichy era; as historians later verified, approximately 1 per cent of the population actively participated in military-style resistance networks, just as approximately 1 per cent willingly participated in the collaboration by marching around in real or virtual jack boots while helping the Nazis carry out the deportations of Jews and other atrocities. (One per cent may sound like little, but in a population of 40 million, these were sizable numbers.)

As for the rest of the population, they made small or large gestures in either direction, or they sat on the proverbial fence waiting to see which way the wind would blow. They were bystanders – informed bystanders, that is, since the oppression of their Jewish neighbours was happening under their noses.

London, 1942: General Charles de Gaulle greets sailors who joined his Free French forces.The Associated Press/The Associated Press

Today these facts have been acknowledged by most of the French, but for 40 years the French government propagated a fully-developed myth. It went like this: Yes, atrocities were committed on French soil, but they were uniquely the work of the occupying Nazis and their collaborationist henchmen in Vichy. They had nothing to do with the true France, which had resided in London from 1940 until 1944 with the government-in-exile of General Charles de Gaulle, who was aided at home by an all-pervasive French Resistance. General de Gaulle had deliberately created this myth of an all-encompassing resistance because he believed that a shared narrative of winning the war would promote peace among his divided countrymen. And he was right – for a time.

Postwar generations of French children were taught that their parents and grandparents had heroically fought the Nazis, while those families whose collaborative deeds were too widely known to dissemble claimed they had been playing a double game: They had merely pretended to collaborate, they said, but they had really been acting for the Resistance.

Those who died had died as martyrs – Mort pour la France, for the sake of the fatherland – including the deported Jews. They had died, it was claimed, for the fatherland, not by the hand of the fatherland, which was a lot closer to the truth. Remarkably, in spite of living memory, the phrase Mort pour la France was inscribed on many Jewish headstones in the famous Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris. Decades later, when truth broke through, some of these were reinscribed to read “Murdered at Auschwitz.”

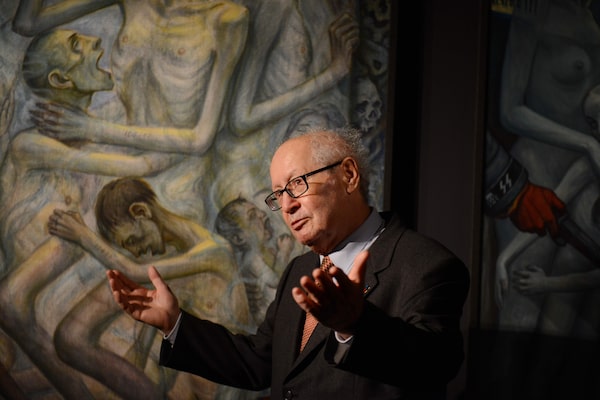

Serge Klarsfeld, shown at the opening of an Auschwitz memorial in Poland in 2018, tracked down ex-Nazi Klaus Barbie in Bolivia and had him extradited to France.BARTOSZ SIEDLIK/BARTOSZ SIEDLIK/AFP/Getty Images

As usual, it took individuals – impassioned individuals – to forcibly shatter the carapace of falsified memory.

In France, it was Serge Klarsfeld. His father had been arrested and killed by Klaus Barbie, the Nazi in charge of operations in Nice. Serge’s wife, Beate, was a German Protestant who knew nothing about her country’s recent history before she came to Paris as a student in 1960 and met Mr. Klarsfeld, who filled her in.

Two decades later this couple tracked down Barbie, in Bolivia, and successfully persuaded the French government of the day to request his extradition to France to face trial for his war crimes against the Resistance and the Jews. On Feb. 6, 1983, Barbie was effectively kidnapped and returned to France. He hadn’t changed: En route he opined that he was sorry about every Jew he did not kill.

Barbie’s return to French soil occasioned a violent public controversy about Holocaust memory whose dissonance can still be heard today. In 1985, I published Unhealed Wounds: France and the Klaus Barbie Affair, a book about the implications of his return for the collective memory of the Holocaust in France.

And in the late 1990s, when I returned to the subject for my book Long Shadows: Truth, Lies and History, the cacophony had not yet died down. In effect, the unexpected return of Barbie to France had effectively pierced layers of occulted historical memory, forcing the French to confront the reality of the Vichy collaboration. The painful recovery of fact and memory decades after the war’s end represented the beginning of the second stage in the process of Holocaust remembrance.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel gives a speech during her visit to the former Auschwitz site in Poland this past December. This was just the third time a German chancellor has visited Auschwitz, and Ms. Merkel made the trip as her country grappled with a resurgent far right and anti-Semitism.JOHN MACDOUGALL/AFP via Getty Images/AFP/Getty Images

A man visits Berlin's Holocaust memorial on Jan. 20. Designed by U.S. architect Peter Eisenman, the memorial is made up of 2,711 concrete slabs, and was opened in 2005 to mark the 60th anniversary of the Second World War's conclusion in Europe.Michael Sohn/The Associated Press/The Associated Press

How was, and is, the Holocaust remembered in Germany, the principal perpetrator state?

At first, like everywhere else, there was silence. After 1945, the Germans pointedly put aside the past. It wasn’t easy. The new Federal Republic of Germany needed to rebuild. But with whom?

The standing judiciary had condoned atrocities and was compromised. So were the bureaucrats. But someone had to run the country. Holding their noses and breathing a tacit sigh of relief – after all, Hitler was dead and his henchmen had been tried at Nuremberg – German society tried to move on.

A generation passed before the silence broke. In the late 1960s, an anti-establishment youth “revolution” swept the West. But in Germany the focus was specific.

For the first time, young Germans began to ask aloud what “the fathers,” as they called them, had done during the war – and when they learned the truth, families splintered. Many children of former Nazis rejected their parents, committing themselves to social and personal reparations. They rebuilt destroyed cemeteries and synagogues. Some of them left the country to live in Israel.

My own travels through Germany during the 1990s brought me into contact with many members of this generation, including the psychologically shattered offspring of top Nazis, such as Niklas Frank, the son of Hans Frank, Hitler’s gauleiter in Poland; and Martin Bormann Jr., a man whose very name made people shudder.

Beate Klarsfeld, shown alongside husband Serge, gives an interview in Washington in 2019.NICHOLAS KAMM/NICHOLAS KAMM/AFP/Getty Images

I suggested earlier that passionate individuals can successfully disrupt official silence or myth-making, and extraordinarily, it was Ms. Klarsfeld, who was among those who initially blew things apart in Germany.

In November, 1968, Ms. Klarsfeld attended the Congress of Christian Democrats in Berlin. Presiding was Kurt Georg Kiesinger, then-chancellor of West Germany, who had worked for Joseph Goebbels as deputy director of radio propaganda for foreign countries.

Dressed as a prim secretary, pencil and notebook in hand, Ms. Klarsfeld approached the podium just as the chancellor was about to speak. “Nazi! Nazi!” she screamed. Then she slapped his face. There was pandemonium. She was sent to jail. But it was worth it, she later told me. The publicity was worldwide.

Twenty more years passed during which the stirrings of repressed memory increased. Then in 1985, the taboos of Nazi and Holocaust memory were literally unearthed at the site of the former Gestapo headquarters in Berlin.

There had been debate over what to do with the problematic site. Now another group of young people – already the grandchildren of Nazis – was demanding that “a site of contemplation” be built there. The authorities dithered and dallied.

On May 8, 1985, on the 40th anniversary of the end of the Second World War, a small band arrived at the spot. They carried shovels and signs that read, “Dig where you stand.” And before a crowd of astonished onlookers, they began to hack at the earth, to dig into history, to physically excavate the foundations of a still-taboo past. And that was not all.

On that same day, then-president Richard von Weizsaecker delivered his memorable speech to the German parliament about the country’s crimes against the Jews and the need to keep memory alive. “Anyone who closes his eyes to the past is blind to the present,” he said. “Whoever refuses to remember the inhumanity is prone to new risks of infection.”

German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier lays a wreath in Berlin this past Nov. 8 for the anniversary of Kristallnacht, a night of anti-Jewish pogroms in 1938.SOEREN STACHE/SOEREN STACHE/DPA/AFP via Getty Images

In retrospect, Germany’s second stage of Holocaust memory, which began with the youth revolution of 1968, has been remarkably successful. In 1970, just two years after Ms. Klarsfeld’s famous slap, West Germany’s then-chancellor Willy Brandt fell to his knees before the Warsaw ghetto memorial in a breathtaking act of repentance.

Mr. von Weizsaecker’s speech to the Bundestag was one of the most powerful moral statements of the 20th century. In Germany today, it is a crime to deny the Holocaust; school children are educated about the truth of the Hitler era and take class visits to concentration camps. Memorials abound. Germany has paid reparations and is a staunch supporter of Israel.

It is true that Germany’s Nazi past will remain “unmasterable,” to quote the late novelist Gunter Grass, a truth that is difficult for many to bear.

In the late 1980s, the famous Historians’ Debate over how to remember the Holocaust pitted intellectuals of the right (who argued that there was no moral difference between the crimes of the Soviet Union and those of Nazi Germany, and that Germans should not feel special guilt over the Holocaust) against those on the left (who asserted that the memory of the Holocaust could never be normalized).

It is also true that we are seeing a revival of this discourse today with the rise of the extremist Alternative for Germany in the former East Germany. Will this movement be able to reverse Germany’s progress? My own sense is: probably not, but caveat emptor. We live in unpredictable times.

Visitors to the Yad Vashem museum in Jerusalem look at the Hall of Names, a tribute to some of the millions of lives lost in the Holocaust.EMMANUEL DUNAND/EMMANUEL DUNAND/AFP via Getty Images

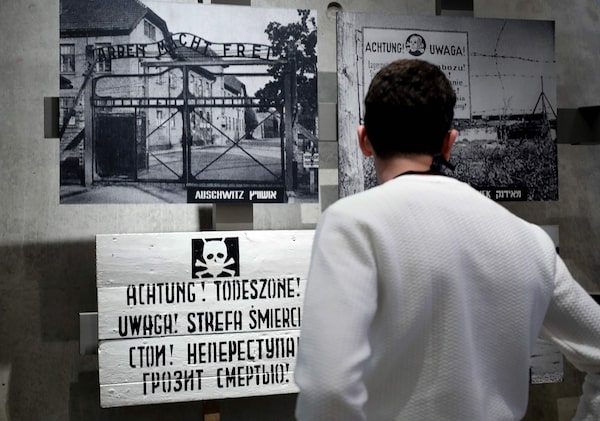

A Yad Vashem visitor looks at an exhibition showing the Auschwitz gate, whose German inscription means, 'Work will set you free.'EMMANUEL DUNAND/EMMANUEL DUNAND/AFP via Getty Images

Of the many controversies that have dogged Holocaust remembrance, none has been more tenacious than Holocaust denial. Holocaust denial is, and has always been, informed by anti-Semitism, since the facts of the Holocaust are beyond question. Holocaust denial was the “fake news” of the postwar era. Many deniers operate according to Goebbels’s theory of The Big Lie, in which Hitler’s minister of propaganda made the following claim: “If you tell a lie big enough and keep repeating it, people will eventually come to believe it.”

That this has not happened with Holocaust denial, in spite of efforts that have spanned the globe, is due to a number of factors: the authenticity of survivor narratives, professional archival research, the physical visibility of the death apparatus and the Nazis’ own meticulous record keeping. It is also due to vigorous and continuing rebuttal.

Holocaust denial and the attendant effort to shape Holocaust memory started immediately after the war as Nazi operatives destroyed evidence. Deniers have been intellectuals and other individuals with access to microphones; they have been governments, such as Iran’s; and they have been political leaders.

In France, for example, Jean-Marie Le Pen, the loathsome first leader of the National Front (now called the National Rally), called the gas chambers “a detail of history,” and he was not alone. More recently, Poland has flirted with denial with a law that makes it a crime to accuse that country of complicity with the Holocaust.

Deniers have been professional teachers with access to children and bogus scholars with access to sympathetic publishers. Here in Canada, in the mid-1970s, Ernst Zundel was convicted of “willfully promoting hatred against an identifiable group” for having published The Hitler We Loved and Why, and Did Six Million Really Die? The Truth At Last. In 1984, the Alberta public-school teacher James Keegstra was convicted on similar grounds for teaching that the Holocaust was a hoax.

Holocaust denier Ernst Zundel wears a hard hat reading 'freedom of speech' outside a Toronto courtroom in 1985.Edward Regan/The Globe and Mail/The Globe and Mail

Free speech is a cornerstone of democracy – and in democracies, controversy over what are the limits to free speech is never-ending. But free speech can also serve as the refuge of scoundrels.

With regard to the Holocaust, it is of utmost importance for liberal democracies that the denial narrative never assume respectability, for the denial of historical fact of any kind opens the door to danger, and this is especially true when it comes to genocide.

Historical memory is similarly shaped by museums through their necessarily simplified choice of narrative; in fact, if you want to know the national story of any country, head straight to an important museum and you’ll find it there. And museum narrative is frequently subject to revision.

We’re witnessing this in Canada today as museums rethink their exhibits on First Nations. Elsewhere, if you happen to visit the old museum of history in Budapest, for example – “old” because a new one is planned and has already been accused of whitewashing history – you will note that the curators were a lot more interested in the hated Communist and Ottoman eras than they were in the Holocaust, even though 565,000 Hungarian Jews were deported to Auschwitz in the last days of the war with the ready co-operation of the Hungarian government.

At Yad Vashem, a display shows Star of David-shaped badges used by the Nazis to identify Jews.EMMANUEL DUNAND/EMMANUEL DUNAND/AFP via Getty Images

Like it or not, museum messaging is inevitable precisely because every exhibit is presented through a selected lens of history. When I visited the groundbreaking Yad Vashem Holocaust memorial museum in Jerusalem in the 1980s, the very first item in the exhibition made the widely debated claim that the Allies knowingly stood by while the Jews of Europe were being destroyed.

The last space in the museum also communicated a political message about memory. Shaken by Yad Vashem’s seminal depiction of the Holocaust in words and pictures, the visitor exits on to an outdoor terrace where stands a moving bronze sculpture depicting stylized human figures hanging on stylized barbed wire in various attitudes of agony, by the Yugoslav artist, Nandor Glid.

Immediately beyond this art work rise the densely populated hills of Jerusalem where rooftops glint in the light of the sun. This final vision was, to me, the museum’s most important communication about Holocaust remembrance and the historical significance of Zionism. The New Jerusalem. The Jewish people – reborn from the ashes.

Elsewhere, Holocaust museums and memorials have been more controversial. For example, in the late 1970s and the 1980s, the plan to build the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington became mired in quarrel. The dispute centred around two men: then-president Jimmy Carter and writer and Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel, the explorer of the dark soul of survival.

Mr. Carter was a religious Christian who believed in universality; he wanted the museum to represent Nazi crimes not just against the Jews, but also against a wide range of people, including Poles and other East Europeans, homosexuals and people with disabilities. This was already a murky subject, as you may imagine, given the presence of Nazi collaborators in many Eastern European states.

Mr. Wiesel, on the other hand, saw the Holocaust as a uniquely Jewish event – literally, as a sacred subject. He argued that while not all victims were Jewish, all Jews were victims, destined for annihilation solely because they were born Jews.

The question on the table was: Whose suffering should be included? That of the six million Jews alone? Or of the four million to 20 million non-Jewish victims – whose numbers basically depended on who was counting?

These two men were not going to agree. Eventually, Mr. Wiesel left the planning board. And he did not show up for the inauguration of the museum.

Jimmy Carter and Elie Wiesel, shown in 2008 and 2009, respectively.Reuters, The Globe and Mail

As though Holocaust denial and museum controversies were not sufficient challenges to the narrative of memory, disputes of a different nature have divided the community of survivors, themselves, some of whom have preferred the commemoration of their unprecedented life tragedy over professional history.

In retrospect, commemoration was perhaps destined to conflict with the dry pursuits of scholars combing through archives, since personal recollections may, or may not, correlate with the rigours of historical fact.

In his 1961 book, The Destruction of the European Jews, the first archival work on the Holocaust, historian Raul Hilberg paid a heavy price. When he told the world that his research indicated that the number of murdered Jews may have been closer to five million than six million, anger erupted. The six-million figure was already settled. It mattered to commemoration. Dr. Hilberg, who was himself a refugee of Nazi Germany, was called an accomplice to Holocaust denial.

I, too, was led to a misunderstanding about history versus commemoration. In the 1990s, I was invited to lecture on Daniel Goldhagen’s provocative book, Hitler’s Willing Executioners, which claimed that ordinary Germans were “willing executioners” because they had been indoctrinated into what Dr. Goldhagen called “eliminationist anti-Semitism.” I had reservations about the fairness of this thesis and had already published my views in a book review in The Globe and Mail. I had barely begun to speak before a woman jumped up and said, “You should be ashamed of yourself!”

What followed was a shouting match among the audience, some attacking me, others defending me, while I sat down in amazement. Yet, all these years later, two remarks from that evening have never left me. A man seated at the back of the room said pointedly, “We don’t need history. We were there.” With sorrow in his voice, someone else said, “In 30 years you can say this. When we are all dead.”

What I came to understand that evening, with compassion, was that the commemoration of experience was what mattered for some people – commemoration and its complement, commemorative history. My criticism of an approved-of book had been perceived, by some, as an attack.

The former Auschwitz site, as seen from the air. Ceremonies marking the 75th anniversary of the camp's liberation are due to take place on Jan. 27.Christopher Furlong/Getty Images/Getty Images

A memorial rose is left on the Auschwitz complex's electric fence. An estimated 1.1 million people, mostly Jewish, are believed to have been killed in gas chambers or by starvation, exhaustion, disease or medical experiments.Christopher Furlong/Getty Images/Getty Images

Contested historical narratives provoke impassioned debate. My favourite example of this was an illustration from the French newspaper, Le Monde, showing a large history book open to the year 1943. On one side of the book are dozens of tiny people pushing to close the page. On the other side, the same number of Lilliputians struggle to hold it open.

So we should not be surprised that the Holocaust, which was unprecedented in so many ways, continues to engender argument even among those who would not dream of denying its existence. But today we must ask a new question, which brings me to the third stage of my timeline of remembrance. How will the Holocaust be remembered after the remaining survivors die and its specific horrors recede from living memory?

I could be wrong. But I can suggest a few possibilities, based on present trends.

First, the bad news. In her recent studies of what she calls collective or cultural memory, reputed German scholar Aleida Assmann has argued that the shelf life of front-burner historical memory is approximately 70 to 80 years. That’s where we are now with regard to the Holocaust.

What this means is that it will become increasingly important to keep a factual narrative of memory alive in the face of possible distortion, forgetfulness or both.

The good news is that much good work has already been done. There has been a concerted effort to record the testimony of Holocaust survivors. These recordings will benefit future generations.

Another piece of good news is the creation of excellent Holocaust museums and memorials around the world. But memorials, too, must be curated properly, for when they are not, the results may be appalling.

For example, in a residential neighbourhood of Berlin, I once came across a memorial, made of mirror glass, upon which were engraved the names of the deported Jews of the district. It stood in the middle of an open-air food market and from time to time the vendors squinted through the names of the dead to apply their lipstick.

Max Filobelo, a student at Westchester Academy for International Studies, asks a question to Holocaust survivor William Morgan at an interactive exhibit at the Holocaust museum in Houston in 2019.David J. Phillip/The Associated Press/The Associated Press

Many schools around the world now include Holocaust education in their curriculum, but how the subject is taught matters. Teachers must be trained to present difficult material in ways that do not overly traumatize youngsters, while at the same time offering them ways of using this hard learning to make a difference in the world.

I came to this conclusion on a visit to Nuremberg, where I heard a survivor tell her horrifying story to a group of shocked high-school students. One youngster raised his hand and asked the survivor what German children like him could do to ease her suffering. “Nothing,” she replied.

From her point of view, she was right. It was not her job to smooth reality to make that child feel better. But my heart went out to that boy – that descendant of Nazi Germany. He needed not to feel helpless before the enormity of his inheritance.

Carefully calibrated school courses, museums and memorials must offer a way forward, psychologically. To believe that one can learn hard truths, then make a difference to one’s society, will help to keep the memory of the Holocaust alive in positive ways.

In pondering the future of Holocaust memory, we might wish to return to the seminal debate between Mr. Carter and Mr. Wiesel. Mr. Carter’s secular vision was that the Holocaust was a crime against the Jews, but also a universal crime against humanity at large. Mr. Wiesel’s view of the Holocaust claimed Jewish particularity and had a quasi-religious cast, as evidenced when he said, “One should take off one’s shoes when entering its domain; one should tremble each time one pronounces the word.”

Skulls of Rwandan genocide victims are shown on display last year at the Ntarama Genocide Memorial in Kigali.JACQUES NKINZINGABO/JACQUES NKINZINGABO/AFP/Getty Images

How might this controversy unfold in the future? I think we can already see where it is going.

After the genocides in the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda in the 1990s, in which similarities with the attempted Nazi genocide of the Jews were visible, Holocaust and genocide studies began to flourish in universities, including here in Canada. These studies are historical, but they are also interdisciplinarian in nature. The hope is that by incorporating the disciplines of psychology and sociology, for example, we will learn more about how and why such events occur and also how they might be prevented. A broader scope of study appears to be the new direction.

An interesting example of this widening scope took place just last summer. In the United States and elsewhere, people had used the phrase “concentration camps” to refer to the detention centres at the U.S.-Mexican border where children were separated from their parents and held in abominable conditions. In response, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum issued a statement in which it rejected any possible analogies to the Holocaust, or to the events leading up to it. The uniqueness argument, in other words.

What followed was most revelatory. Hundreds of scholars of the Holocaust signed a public letter stating that the museum’s position made learning from the past almost impossible – and was far removed from contemporary scholarship.

Migrant children are led single-file between tents at a detention facility in Tornillo, Texas, in 2018.Mike Blake/Reuters/Reuters

The survivor recordings, the museums and the monuments, along with the extensive scholarly research that has informed the consciousness of the world, will all help keep the memory of the Holocaust alive. So will events such as Holocaust Remembrance Week.

Yet, at the same time as we rightly fight to preserve historical memory, we must realistically knowledge the potential lifespan of collective remembrance, the time-related slide into forgetfulness, the incessant politics that have always surrounded Holocaust discourse, and the real challenges being faced by the liberal international institutions and values that came into being as a result of the Nazi genocide, including the European Union.

Article 2 of the EU states that the organization is founded on values of respect, freedom, democracy and the rule of law, yet the EU continues to fund the illiberal regime in Hungary that has vilified George Soros and his Open Society Foundations with Nazi-style, anti-Semitic tropes. Resistance to this must harden.

A continuing positive consensus about the Holocaust will require active vigilance in the effort to protect all liberal democracies – the open societies that value ethnic diversity and religious tolerance.

All the same, change, like taxes and death, is inevitable. Nothing remains the same. And given the current trends in Holocaust studies, for example, it is possible that 50 or 100 years from now the Holocaust may primarily be remembered as a “first among others,” within a context of other genocides.

This should not worry us, in my view, for the “lessons of the Holocaust” are both particular and universal. As the scholars who opposed the Washington museum’s narrow approach to Holocaust history pointed out, what is and will be important is the ability to learn from the past.

The core learning future generations must acquire, in addition to the facts of Holocaust history, will be to recognize the impulse to genocide, how and why it starts, the propaganda tools it employs to persuade, and the known consequences of silence and indifference. I think this learning must also include the somewhat rueful acknowledgement that most humans are susceptible to propaganda in various degrees, which is why early-stage vigilance is so crucial.

Viewed from this perspective, the Holocaust may one day be remembered not only as tragic, but also as transformative in our understanding of humankind’s darkest impulses.

Galerie Bilderwelt/Galerie Bilderwelt/Getty Images

Keep your Opinions sharp and informed. Get the Opinion newsletter. Sign up today.