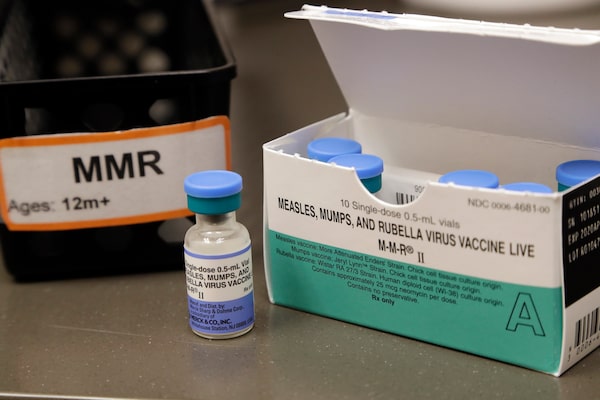

A dose of the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine is displayed at the Neighborcare Health clinics at Vashon Island High School in Vashon Island, Wash., on May 15, 2019.Elaine Thompson/The Associated Press

The measles vaccine is one of the great success stories in the history of medicine and public health.

When it was first introduced, in 1963, about 2.6 million children were dying from the viral infection each year.

Tens of millions more were left with severe disabilities. Measles can cause dangerous swelling of the brain, and it was a leading cause of deafness, blindness and developmental disability in children.

We know, too, that measles can cause “immune amnesia” – damage to the immune system that can leave patients susceptible to other infections.

Measles deaths fell steadily until 2019, when the global number dipped below 90,000 worldwide. There was serious talk of eradication, as had been done with smallpox and was being attempted with polio.

But vaccines only work if you get them into people’s arms, and that’s not happening as universally as it should.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, a lot of children missed their routine vaccines, and catching up is not easy, particularly in the developing world where public health programs have been overwhelmed.

Another unexpected consequence of the pandemic is how it has fuelled growing resistance to vaccination and other infectious-disease mitigation measures. In Western countries, rates are dropping because a small but growing minority of parents are refusing to get their kids vaccinated.

And that suits measles just fine – because it is very good at exploiting gaps in coverage.

Last year, there were an estimated 9 million measles cases worldwide, and 136,000 deaths – with both figures representing huge jumps from the previous year.

Measles has not only continued to ravage the developing world, but regained a foothold in wealthy countries. In Europe, there were more than 30,000 cases last year, up from 941 in 2022. At the end of 2023, 49 countries were experiencing “large and disruptive” outbreaks, according to the World Health Organization.

Now we’re seeing cases pop up with increasing frequency in North America. Canada – where measles was declared eliminated in 1998 – has already seen six cases to date this year, after 12 last year. To date, most of those cases are imported – meaning children were infected on trips abroad. With March break approaching, this risk grows.

The U.S. has seen 35 cases to date in 2024, including a worrisome outbreak in Florida, where nine children are known to have been infected so far; none of them travelled abroad to countries where measles is commonplace.

Those numbers don’t seem very large, but don’t forget that measles is one of the most contagious infectious diseases in existence. Every measles virus carrier infects, on average, between 12 and 18 others if they are unvaccinated. (By comparison, a carrier of SARS-CoV-2 infects one to two others.) Worse yet, people with measles are infectious four days before and four days after the telltale rash appears. It spreads quickly and silently.

What’s really troubling though is the response to the threat of measles, which has ranged from an indifferent shrug to outright denial of the risk and the rejection of mitigation measures.

Most people alive today have never seen measles, so they don’t see it as a threat. The effectiveness of vaccination has, paradoxically, led people to think vaccination is unnecessary.

In the wake of COVID, many have also adopted an “it’s-just-a-cold” attitude toward most every infectious disease.

Florida’s surgeon-general Joseph Ladapo has taken it one step further, rejecting public health measures. He told parents that unvaccinated children can attend a primary school in Broward County even though there is currently a measles outbreak there. (The current federal recommendation is that they should stay away from school for 21 days.) This is clearly politically motivated. A lot of people didn’t like COVID lockdowns, and school closures in particular.

It’s fine for people to think that freedom trumps public health. But now we’re seeing a kind of civil war over vaccination, vaccine mandates and infectious-disease mitigation measures in particular.

Measles is just the canary in the coal mine. When it comes roaring back – and at this rate, it almost seems inevitable – we will see a resurgence of other conditions like whooping cough, chickenpox, mumps and other old-world diseases we have controlled effectively with vaccination.

It’s bad enough to see decades of public health progress undone by opportunistic political dogma. Sadder still is knowing the collateral damage is going to be children.

In this day and age, no child should ever die of a preventable infectious disease. That’s not freedom – it’s a perversity.

André Picard

André Picard