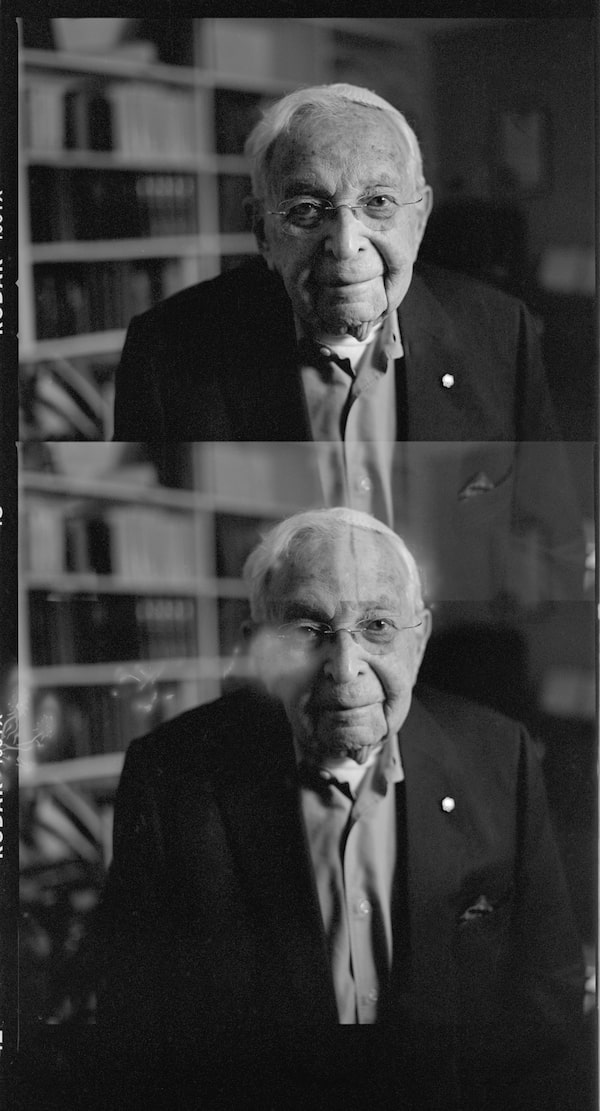

Now almost 99 years old, rabbi Erwin Schild recalls his time at the Dachau concentration camp during the Second World War with 'naked fear – a fear I can never truly shake.'Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

Erwin Schild is rabbi emeritus of Adath Israel congregation in Toronto, and the author of four books.

Old age, they say, is not for the faint of heart. Now that I am nearly 99 years old, I feel that expression in my bones.

Ordinary tasks turn into major operations. A powerful nemesis lies in wait at all times: the danger of falling. I use a walker and a wheelchair. I have to use interior lifts to go from one floor to the other, and a whole elevator to leave or enter my home. I have to accept the aches and infirmities of an aging body and, if possible, defy the occasional recalcitrance of a worn-out mind. I need help to shower, to get dressed. I have to drag my oxygen-machine with me, and to have it charged when needed. I do not drive my car, and I cannot go anywhere unattended. I get tired easily. I wistfully remember that just 15 years ago I was running three to five miles several times a week.

If you are not strong and determined in the face of these challenges, you might just give up. Why bother?

But each day brings its own blessings. And it is January, the beginning of a new year, a season and reason to celebrate with those closest to you. Over the past few days, I have been visited by family: my children, Daniel, Judith and Naomi, some beloved nieces and nephews, many of my 13 grandchildren, and some of my 50 great-grandchildren, who are now scattered across Canada, Israel and the United States. I was able to see Ahuvah Noble again – my sweet great-great-grandchild, now one year old, visiting from New Jersey. She really is a gift of my age. I am grateful that before Laura, the love of my life and her great-great-grandmother, passed away in November, she was able to meet her.

I am blessed to see them all here, filing through the parlour of my humble home, nestled in a quiet street just off a major artery in north Toronto. There is cake on the kitchen table. There is plenty of food and warmth. We take pictures to remember these moments by. They are happy and secure, and that’s the way it should be – parents steering their children in safety.

Rabbi Schild, his wife and three children in 1960.Courtesy of Erwin Schild

Five generations of Rabbi Schild's family gather together in October, 2017. From left: Sori Noble, great-granddaughter of Rabbi Schild; Rabbi Schild with great-great-granddaughter Ahuvah Noble; Laura Schild; Naomi Weitz, the baby's great-grandmother; and Mira Epstein, her grandmother. Laura Schild died on Nov. 27, 2017, just weeks after the photo was taken.Courtesy of Erwin Schild

But I know in my heart that there is something they do not have – something that I do – and while I would never wish it on them, I do not envy my comfortable family, either. This thing has ripened and forged me, just as it has tragically done for the millions of refugees in the world, fleeing countries with such desperation that they’d leave behind everything they’ve ever known.

That thing is naked fear – a fear I can never truly shake, born of a period of sheer terror in which I was imprisoned in Dachau concentration camp at the hands of the Nazis.

That fear in my past gifted me the wisdom that I have long held in my heart, that no matter what misfortune I suffer – whether it’s the ocean of challenges that crash against my shore as I age or any other tragedy I have faced, including my tribulations upon arriving in Canada – I can have perspective. That fear inspired a vow I made to myself in Dachau: that if I should get out alive, I would never allow any future adversity to depress or defeat me.

On Jan. 26, the 80th anniversary of my harrowing escape from Germany and rebirth as a refugee, I celebrate a promise that continues to steel me.

Baby pictures of Erwin Schild, who was born in a suburb of Cologne just after the First World War.Courtesy of Erwin Schild

His parents, Hermann and Hetti, are shown in their engagement photo from 1912. Later they would run a shoe business in Cologne.Courtesy of Erwin Schild

I was blessed to be born just after the Great War, when we believed that we would never have to name it anything else because there would never be a second one. I grew up in Mulheim, a suburb of Cologne on the beautiful banks of the Rhine River in Germany. There, the people take to heart the lyrics of their songs: that living on the Rhine confers a unique ability to enjoy life, as well as a good-natured, peaceful personality. My marvelous family was no exception. My father, Hermann, was a hard worker, a clear-eyed mediator and a voracious reader who taught himself French through correspondence. He ran a shoe business with my mother, Hetti, a self-reliant woman who loved going out to concerts, theatres and clubs. Somehow, with some domestic help, she managed both the store and the household, which included my worldly older brother, Kurt, my kind younger sister, Margot, and a family of tenants upstairs.

While Kurt was indifferent to school – preferring to focus on his social gifts – my parents nourished my curiosity, and I excelled academically. It was a good life: In my first three years of high school, I would relish the morning walk up the Wallstrasse, turn into Buchheimer Street at the corner where our family’s second shoe store was located and then cut across the square in front of the church. Sometimes, I would drop in at the Schubach family home to enjoy a piece of Mrs. Schubach’s cake. On the way home, I would walk my loyal friend Jojo Mohl’s dog, a German shepherd named Chasseau, who would wait at the door for me every afternoon. I dreamed of wearing the distinctive white cap of the Primaner, the upper-class scholar, and becoming a professor of literature or philosophy – or maybe even a rabbi. As a child, I fell in love for the first time, with Ruth Speier-Holstein, the oldest of our family doctor’s three daughters – deluging me with emotions that I had read about but never experienced before. I fervently shared in German patriotism and the mystical love for the Fatherland – and why not? Life was beautiful.

Adolf Hitler greets admiring supporters in Nuremberg in 1933, the year he rose to power as chancellor of Germany.

History books will tell you that everything changed on Jan. 30, 1933, when the National Socialist German Workers' Party rode a wave of extreme patriotism and chauvinistic nationalism into government with the appointment of Adolf Hitler as chancellor. The reality, though, is that things were dire before that. The German economy was in grave and deepening crisis; millions were unemployed; the working class became impoverished; and far-left communists and far-right members of Hitler’s Nazi Party were growing in numbers, sparking bloody battles in the streets.

But history books can be cold and impersonal, divorced from the emotions of people’s lived reality. One does not tend to realize you’re living through history until it’s over.

While Hitler shamelessly campaigned on an anti-Semitic platform – which was even spelled out, plain as day, in his virulent book Mein Kampf – most Germans did not take that part of his political message seriously, intrigued instead by his prescriptions for blunt civic pride after Germany’s Great War humiliations and Weimar Republic governments that were seen to be meekly following the Treaty of Versailles. Even when the Nazis started enacting their anti-Jewish agenda as soon as they took over, Jews and opponents of the regime optimistically believed that it would only be a year before the party would get swept away democratically for failing to keep the rest of their ambitious promises. The Jewry had been woven into the fabric of German life for more than a century, after all, and that was a comfort to a generation of German Jews – which included my parents – who refused to read the writing on the wall, or even the country’s long history of blending nationalism with anti-Semitism. I myself read the newspapers regularly and observed the turbulent political scene, but I did not realize that the violent currents in public life would affect me personally; I had been happy, sheltered and favoured.

These were miscalculations on the same scale as Hitler’s prophecy that his Third Reich would last a thousand years.

Erwin Schild's grade-school class in 1927. Two years earlier, Adolf Hitler restarted the Nazi party in Bavaria, where it had been previously banned.Courtesy of Erwin Schild

Erwin Schild in 1931. By this point, Jews in Germany were facing increasing official discrimination as the Nazis' political influence increased.Courtesy of Erwin Schild

It is hard to explain the kind of infiltrating fear that gnaws in your gut when your life is under an existential threat – the exquisite fear that arises when the world’s darkest troubles, so vast and overwhelming when you read about them in the newspaper, swirl around and touch down on your own home like a tornado.

Just one year after I started elementary school, Hitler had officially restarted the National Socialist German Workers' Party, in 1925. By the 1930s, Jewish people learned to avoid attention and be on our best behaviour, even as signs reading “Juden unerwunscht” – “Jews not wanted” – appeared in front of restaurants and places of commerce and entertainment.

Weeks after Hitler became chancellor, the government proclaimed a one-day boycott of Jewish businesses such as my parents' shoe stores, with storm troopers posted at store entrances to intimidate would-be shoppers. Two months later, I had my bar mitzvah, and so I came of age – a grim irony, given that the pain that would come in years ahead would force me to grow up much more quickly than I bargained for.

My visions of wearing the Primaner cap were dashed when the Nazis eliminated them as part of its reforms of the education system. German boys were expected to don brown uniforms with belt, shoulder strap, swastika armband and caps adorned with the Nazi insignia; while my comrades were generally good-natured and my friends remained my friends, Jewish students looked with dread at the uniforms, particularly at the dagger that completed the older boys' outfit. Jewish contributions to German life, as well as the work of Jewish writers and artists, were excised from the curriculum; pseudo-scentific racial studies were given supremacy in science class.

Then, on Nov. 9, 1938, a young Jewish refugee named Herschel Grynszpan assassinated diplomat Ernst vom Rath, sparking a state-sanctioned call for merciless retribution. Glass littered the ground as Jewish businesses were looted, hundreds of synagogues were burned down and German Jews were rounded up and beaten. It was the night of crystal, the Nazis called it – Kristallnacht.

The next day, as the pogrom continued, looters set fire to the library of the Wuerzburg seminary, where I had been studying for the past year. With all the impudence of my 18 years, I bolted headlong into the ransacked building and managed to retrieve a few Judaic items before returning to my dorm. Before long, however, uniformed men arrived at our door and forced us to march through the street, where we were jeered and leered at on the way to jail.

Days later, I was moved to Dachau concentration camp: the Nazis' destination for the doomed.

Jewish slave labourers work in an ammunition factory at the Dachau concentration camp during the Second World War.The Associated Press

Trauma blots out unbearable memories, and beyond the occasional, unbidden flashes of remembrance – profound fear, constant hunger, physical and mental torment and the loss of every shred of human dignity – my recollections of Dachau are sketchy. I remember, though, that our belongings were taken away and that our heads were shaved. I remember cold showers and hard wood-plank beds, and that our clothes were confiscated and replaced by the rough, striped, prison-camp uniform that was too thin to ward off the November wind coming down the Bavarian mountains. Somehow, I managed to hold onto a sleeveless sweater my mother had crocheted for me, and I wore it under the shirt, like secret armour. When I was told, by some miracle, that I was to be released after a month of cruelty – on the condition I leave Germany – I handed my sweater to a friend, hoping that it would guard someone else, too. I still remember the veteran soldier who said that one day in Dachau was worse than his four years in the brutal trenches of the Great War.

After I was released, I joined the many German Jews who sought to flee. Thousands already had, finding it easy to escape to desirable countries such as France, Britain and Holland just a few years ago. But by 1938, the swelling stream of refugees prompted most European countries to tighten their immigration laws and close their borders. The United States accepted only a small number of German-born immigrants, bound by an annual quota that had been fixed long ago, when it had set such limits for natives of all other countries. The higher your wait-list number, the smaller your chances of survival in this lottery of death. The United States never did change its rule.

Meanwhile, Jews in Eastern Europe and the Balkans – traditional countries of origin for Jewish migrants – feared Nazi expansionism, and crowded the remaining migration lanes out of Germany. With much fanfare, Western democracies convened experts and politicians to discuss the refugee crisis in places such as Évian-les-Bains in France, but a failure to enact solutions only deepened the despair of those Jews trapped in these horror zones. Eventually, countries around the world decided the boat was full – no more. And by the time that reality had sunk in, where finding a place of refuge became impossible, the number of suicides surged.

So the frightening deadline hung over me; fear, abject fear, possessed me. I felt like an animal trying to escape from the hunters who were closing in. I was willing to go anywhere to get out of Germany. But where? I was lucky enough to have some connections, so with increasing desperation, I wrote letters, sent telegrams, applied to rescue agencies abroad and enlisted in emigration schemes – all with no success. A Baltimore yeshiva, a Jewish educational institution that focuses on the study of traditional religious texts, agreed to accept me, but the process moved at a snail’s pace, and how could I wait? A student rescue project organized in Britain to study at a London yeshiva looked more promising. Immigration to Britain had been cut off a long time ago, but there was still a chance for students. Be patient! Wait! Maybe next month. But I can’t wait a month! Maybe next week. Patience! Hope!

More waiting. More letters, glitches, problems, obstacles. Hurry, please, hurry! I waited for the mailman every day as Israel waits for the coming of the Messiah, perhaps bringing news of salvation. In my memory, that month seemed like a long time – an infinity, almost. Terror has a way of overcoming even forces of physics.

As the days spooled on, the panic in the pit of my stomach grew like a disease. The German soil burned underneath my feet – I had to get out. I focused on things that felt like banalities, but were really rather extraordinary choices for a teenager to have to make. I should get my suitcase ready, just in case! I’m allowed one suitcase and just 10 German marks. My photo album? Might as well take it. My old drawings – I’m so attached to them. But really – who cares! Let me go with the clothes on my back! Just let me in somewhere!

I went on last walks and bike rides, saying goodbye to the Rhine and the countryside. My mind was consumed by thoughts: When I leave my home, will I still be whole? Will I still be me, if I am divorced from the past, the people, the language, the sky, the earth?

Stop dreaming! Pull yourself together.

Then one day, weeks into this bleakness, my messiah comes. In my trembling hand is the document at last: the special permit that clears me to cross the border into Holland through the city of Enschede.

The next day, I headed to the train station. I bid an emotional farewell to my family and a few friends: Goodbye, goodbye, tears choking off words; auf Wiedersehen, soon, maybe, God willing. Hours later, I passed through the last German checkpoint, where soldiers ended their cruel interrogations with a threat: “Don’t you dare ever to come back, or you’ll be dead!” After that, in one final, brutal twist, Dutch border police told me that my approved documents were in fact for a different border crossing in Holland, and that I’d have to return to Germany to take the correct train. Only the intervention of two Jewish angels from Enschede, summoned to the border office, spared me from testing the German border guards' threats.

A month later, I arrived at the London yeshiva. I was no longer a persecuted Jew in Germany. I was a refugee. I had been reborn.

Rabbi Schild holds up a slide to the window to see if he can remember where it was taken.Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

My brother Kurt was one of the last people to escape Germany to the United States, in April of 1940. Five years later, thanks to his devoted efforts, my sister, Margot – who survived detention in several concentration camps and the death march near the Holocaust’s end – landed in Boston. The Allies had officially won the war just two months before.

But my friend Jojo, who was incarcerated in Cologne’s most infamous jail, was shot dead by the Nazis the day after he was allowed to leave for his mother’s funeral. My first love, Ruth, died in the Sobibor death camp in Poland. Many of my playmates, my school mates and my cousins did not survive. When my parents finally applied to emigrate to the United States, they received a hopelessly high wait-list number that would have only come up sometime in 1941. By that time, they had already been taken to Riga, in Latvia – my mother in a labour camp where no one survived the gruelling work, my father placed in a separate camp – where they perished in 1943. They answer still the silent roll call in my grieving heart.

The Schild family together: Sons Kurt and Erwin, father Hermann, mother Hetti and daughter Margot. The elder Schilds perished in separate labour camps in Latvia during the war.Courtesy of Erwin Schild

London would not be the end of my trials. In 1940, I and tens of thousands of other German- or Austrian-born non-British males were deemed security risks, and put into miserable, makeshift detention camps – “You’ll be back in a couple of days,” the officers had initially promised when they asked me to follow them. Weeks later, unmarried internees were sent to Canada, to be held as enemy aliens, as absurd as that seems, for the duration of the war.

At least for me, the camps in Canada provided the comforts and discomforts similar to army recruits – austere but adequate barracks, with daily inspections and barbed wire fences but clean sanitary facilities – yet, still, there were psychological pains. There was no precedent for this particular kind of deprivation of freedom, or for the absurdity that your allies were locking you up for being suspected sympathizers of the hated Nazis; in Dachau, at least you knew you had fallen into the hands of your enemy. Anti-Semitism had twisted bureaucratic red tape into a solid chain, barring our entry to Canada.

It took us a year to be reclassified officially as interned refugees. Almost a full year after that, in February, 1942, I walked through the gates of Fort Lennox in Quebec. Truly free.

An internment camp in Île aux Noix, Que., where European Jewish refugees were taken after their removal from Britain.Courtesy of Erwin Schild

I hold no grudge against the British. They wound up saving my life, shipping me out just before the London bombings. I have even worked to repair the shattered relationship between Christians and Jews in Germany through speeches and visits, and in a bit of irony, I was awarded the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany, the country’s highest honour. I dedicated it to my parents, friends and relatives.

And Canada has more than compensated me for her initial rejection, the years of detention, and her hostile indifference to my overtures. I sing our national anthem always with deep feeling, and often with tears welling up in my eyes. One of the great honours of my life was being made a member of the Order of Canada.

Still, the Canadian conscience should not be clear. While studying in London, I remember reading the news about the MS St. Louis, a German ocean liner carrying more than 900 Jewish refugees who became the “voyage of the damned” in 1939 when countries such as the United States and Canada denied them entry, causing many to wind up in death camps. William Lyon Mackenzie King’s administration allowed Germans to take refuge in Canada, but when it came to Jews, as goes the infamous quote that summed up the government’s attitudes, “none is too many.” Today, it’s almost unbelievable that such refugees would not be allowed to land here, or that German Jews would be held in Canada, as I was, on suspicion that we supported the murderers who detonated our lives. But we must believe it, and never forget it, because it did happen. Disbelief would be a disservice.

May, 1939: MS St. Louis prepares to leave Hamburg. Canada turned away hundreds of Jewish refugees on the boat.HO/The Canadian Press

There are 25.4 million refugees around the world, according to 2018 data from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees – marking the biggest spike the organization has seen in a single year. But in trying to escape to safe havens, these desperate people have only found that their threatened lives have become a political talking point. It’s clear that the world risks making the same mistake my parents' generation did: ignoring the lessons of history, when we said we would never forget.

There must be something almost instinctive in the way we do not trust those who are different from us. There must be prejudice in us, to say that if someone’s in trouble, it is self-made, it is their fault. But there should be space in the world for people who need it: I am living proof.

I am proud that Canada has been doing well on taking in refugees, but we should do even more. And we must reject policies that would limit or reduce refugee intake: They are insufficient, and it’s not what Canada, as a blessed and rich country, should be doing. Such policies in Canada and beyond are merely exercises in excuse-making, by politicians looking for reasons not to help. While it may not be done out of viciousness, these rejections are a distillation of our own fears of people who are different from us – just as it was for the Jews during the Holocaust.

In 1988, I returned to Cologne to deliver a keynote to nearly 3,000 Christians as part of Protestants' “Day of the Church,” just a week before the 50th anniversary of Kristallnacht – the night my life changed forever. At a convention centre that had once been the very assembly point from which my parents and sister, together with thousands of other Cologne Jews, had been deported to Riga, I shared a parable of a man, lost in a dark forest. For many hours he wandered, searching in vain for a way out and darkness descended. Then suddenly, he saw a light in the far distance, which slowly came closer and closer: a man carrying a lantern. With profound relief, he ran toward him.

“Thank heavens I found you!” he cried out. “Now you can show me the way out of the forest!”

“I am sorry,” replied the other. “I am lost, just like you, and have been wandering through this forest for a long time seeking an exit. But I can tell you this for certain: The way I came is not the right way. So let us search for the right way together.”

To the ones who make it here: Love this country; it’s a good one. To the ones still trying to enter: Have faith and hope; they are there. And to all refugees, whether you’re still seeking your new home or finding your place within it, hold fast to the wisdom I’ve clutched to so tightly that it has become compressed and pure and certain like a diamond in my hand: Goodness will prevail, as we search for the right way together.

Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail