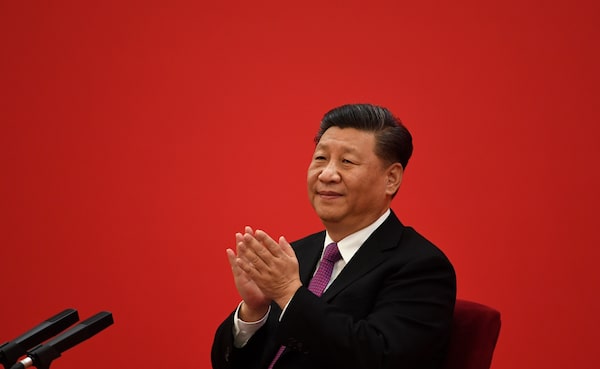

Chinese President Xi Jinping speaks with Russian President Vladimir Putin via a video link, from the Great Hall of the People on December 2, 2019 in Beijing, China.Pool/Getty Images

China has changed.

There is a danger in failing to notice that change, or in choosing to ignore or dismiss it. Witness Michael Bloomberg, the media magnate, former New York mayor and now Democratic Party presidential hopeful. In a TV interview, he was asked why he believed Beijing’s policies are more climate-friendly than they appear.

He answered that he believes China is fundamentally democratic.

“The Communist Party wants to stay in power in China, and they listen to the public,” he explained. “When the public says ‘I can’t breathe the air,’ Xi Jinping is not a dictator; he has to satisfy his constituents or he’s not going to survive.”

A surprised-looking Margaret Hoover, the show’s host, asked him if Mr. Xi is perhaps, indeed, a dictator.

“No,” Mr. Bloomberg said, “he has a constituency to answer to … No government survives without the will of the majority of the people.”

On one hand, he is wrong. The word “dictator” was coined to describe exactly the sort of leadership that the Chinese Communist Party is exercising today: the crushing of dissent and silencing of private communications, the arbitrary arrests and absence of rule of law, the mass incarceration on ethnic grounds.

It is true that Mr. Xi’s hold on power depends, in the long run, on his ability to deliver a standard of living to a majority. As I’ve written, even his repressive rule is founded on popular legitimacy. But that doesn’t mean he’s anything other than a dictator.

On the other hand, Mr. Bloomberg was expressing a sentiment that was often heard, and contained a kernel of truth, during the first half of this decade. In the 2000s and 2010s, under the less tight-fisted rule of Hu Jintao, China was democratizing – not in Beijing (which has never tolerated the idea of a multiparty or multiethnic China), but in its cities, its regions, its institutions, its media and culture.

It was possible then for political and business leaders to talk seriously about influencing China’s direction toward something more open and plural. Only some of them used that talk as cover for greed and self-interest.

A lot of those leaders were caught off-guard by how fast things changed, especially after Mr. Xi persuaded the party to change the constitution in 2017 to make “Xi Jinping Thought” the national ideology, to erase the line between the Party and the bureaucracy, and to extend his term of office indefinitely. China has changed quickly from an authoritarian state with multiple competing institutions of power into a totalitarian state with a single all-powerful leader.

For Mr. Bloomberg to pretend that change has not occurred is either disingenuous or pitifully naive. A number of political leaders – including Prime Minister Justin Trudeau – noticed this change far too late, and only when it had begun to bite them in the back. I keep hearing business leaders pretending China remains an open and hopeful place, long after that hope vanished.

But there is another, equally dangerous version of the myth of a changeless China, one that is on the rise today and is in danger of fuelling an unnecessary new Cold War. It’s the one which holds that China will always be this way – and always has been this way – because Mr. Xi’s anti-democratic leadership reflects something innate in Chinese nature or culture.

The notion that Chinese are somehow suited to authoritarianism, because of Confucian traditions or cultural history, has been popular with everyone from racial fabulists such as the late “clash of civilizations” author Samuel Huntington to pro-Beijing academics such as historian Daniel Bell, who believes Beijing’s “meritocracy” is as good as democracy. Needless to say, the idea is popular in China’s state-controlled media, too.

This belief – that it will always be 2019 in China – is as dangerous as Mr. Bloomberg’s belief that it will always be 2009. It’s hard to find a well-informed Chinese scholar who believes this turn to totalitarianism will outlast Mr. Xi.

“China’s own reform has created a largely democratic society without a complementary democratic polity,” writes the political philosopher Jiwei Ci in his important new book Democracy in China: The Coming Crisis. That mismatch, he writes, “will eventually require that the state democratize in order to preserve its legitimacy.”

The only thing that would endanger that shift, he concludes, would be full-fledged hostility from the West – a Cold War, which would freeze Beijing in a defensive posture.

We don’t know how long the Xi era will last, but it is a moment in China’s history, not its essence. We shouldn’t pretend that this is a hopeful moment – but nor should we buy into the illusion that this is the way it’ll always be.

Doug Saunders, The Globe and Mail’s international-affairs columnist, is currently a Richard von Weizsaecker Fellow of the Robert Bosch Academy in Berlin.

Doug Saunders

Doug Saunders