The hottest political topic in Ottawa this fall is the Liberal government's proposed changes to corporate tax rules.

Well-organized campaigns led by business and professional organizations are urging the government to back down. Other voices, including prominent academic economists and labour leaders, say the government's proposals are on the right track.

The changes, which were announced on July 18, are highly complex. Consultations closed on Oct. 2. The Liberal government responded to the consultations during the week of Oct. 16.

Below is a summary of the proposed changes, an overview of the arguments for and against the proposals and the government's rationale. On Oct. 20, we updated the explanation with a new section at the bottom outlining how the government changed its proposal in response to the consultations.

Who is affected?

This is not an exhaustive list, but your taxes could be affected if:

- You (or a member of your family) own a private corporation, and you (or they) pay out dividends to family members or to a trust;

- Your family corporation keeps some excess earnings within the business’s accounts, which are put towards passive investments;

- Your family corporation pays out surplus earnings as capital gains.

Proposal one: 'Income sprinkling'

What it is: Business owners can distribute income to family members (such as a spouse or adult children), whether or not they directly contribute to the running of the business. If the business owner, which can be a professional, is in a high personal-income tax bracket and the family member is in a lower bracket, the overall amount of tax paid by the family is lower than if all the income was reported by the professional.

What the government would change: Currently, tax rules discourage the paying of dividends to children under the age of 18 for the purpose of lowering the tax burden. This provision is known in accounting circles as the "kiddie tax." The new rules would extend this to older children and other family members. The Canada Revenue Agency would apply a "reasonability" test to see if family members were contributing to the business. Otherwise, the family members could face a higher tax bill.

Business response: Small businesses that pay dividends to family members or trusts say that the policy recognizes the informal contributions that family members often make to a business. They also say that the new reasonability test means more work for the businesses – red tape – to show they are complying with regulations. More than half of doctors – who work as private contractors and bill the government for the work they do – use this corporate setup, according to the Canadian Medical Association. As The Globe's Campbell Clark reported, past governments have promised doctors lower tax burdens through mechanisms such as income sprinkling as a way to compensate for not paying as much directly.

Analysis:

Owners of private corporations benefit from income sprinkling under very specific conditions: they have adult children (minors are not allowed to be part) and/or a spouse that make significantly less money than the principal owner. Kevin Milligan, an economist at the University of British Columbia who has advised the government on tax policy, says that in principle this measure makes sense as a way to raise tax revenue because it is framed as an extension of current regulations. The Canadian Federation of Independent Business surveyed its members who own small businesses and found a majority currently pay compensation to family members. The CFIB is part of a coalition of business groups calling for an extension of the consultation deadline and a reconsideration of the entire plan.

Further reading:

Proposal two: Passive investments

What it is: Instead of taking all profits from a business, the owner can choose to keep some of the money within the corporation's accounts and put it in passive investments such as stocks. Money kept inside the business is taxed lightly, so the investment gets a head start on growing compared with saving outside the business. The government says this investment plan primarily benefits people who have already maxed out other savings vehicles, such as Tax-Free Savings Accounts or a Registered Retirement Savings Plans.

What the government would change: The government is looking at a few options that are aimed at making the passive investments made in corporate accounts face the same overall tax bill as those made through personal accounts. The government says investments from the corporation that are directly related to the business – such as the purchase of new equipment – would not be affected by the change.

Business response: Entrepreneurs say the money that is held in the business – instead of being distributed as salary or dividends – and invested passively creates capital that could be used to grow and invest in the enterprise long-term. It also makes up for the savings and pension that a salaried employee would receive, but that entrepreneurs would not receive. Startup owners say it's a way of balancing the risk involved in launching your own company. Some CEOs of tech startups say this change would reduce some of the incentive to creating your own company. They also say the higher tax rate on passive investments unrelated to their business would leave them with less money to support other business startups through what is known in tech circles as angel investing.

Analysis: This may be the change that is most difficult for the government to make. This is partly because the intention is for the new measures to only apply on a go-forward basis, meaning existing investments would not be affected. Tax experts say accomplishing that goal would be technically challenging. Unlike the other measures, the government does not have draft legislation ready. The Finance Minister recently told a gathering of accountants that his department will ultimately release draft legislation on passive investments for comment before any measures are introduced in Parliament.

Further reading:

Proposal three: Capital gains

What it is: A capital gain is the amount of profit you would make if you sold an asset for more than you originally bought it for. Only half of a capital gain is taxable. Under certain conditions, it is possible to move dividend income (which has a higher tax rate) through multiple corporations and report it as capital gains (which is taxed at a lower rate).

What the government would change: The Income Tax Act already has a section that discourages this activity, but it doesn't cover every possible way dividends can be transformed into capital gains. The government wants to extend the current rules to cover all possible transactions of this type.

Business response: Some family-owned businesses worry this change could make it more expensive for them to pass on their enterprise to their children. The president of the Canadian Federation of Agriculture told The Globe that farm families are concerned about the new rules, though they've been told the government does not intend to negatively affect them.

Analysis: The change is about clarifying an activity that already wasn't supposed to be available, tax specialist Tim Cestnick writes in The Globe. But depending on how the final legislation is worded, it could affect other uses of the lifetime capital gains exemption (LCGE). "For example, where a family trust holds shares of a private company, the LCGE will be unavailable even in cases where the gain is allocated to a beneficiary who is involved in the business, or the shares are distributed to a beneficiary who is involved in the business prior to the sale," partners at Clark Wilson LLP write.

Further reading:

What's next

The government will continue consulting the public until Oct. 2. Some changes go into effect Jan. 1, 2018, while others would retroactively start when the proposal was made public in July.

Finance Minister Bill Morneau speaks to media during a press conference in Vancouver on Sept. 5, 2017.

Ben Nelms/The Canadian Press

Why the Liberals decided to take on small business corporations

It was the summer tax surprise that shocked business owners and caught farmers off guard during the height of the harvest.

Finance Minister Bill Morneau is now under heavy fire from the opposition – and some Liberal MPs – for the way he announced a complex set of proposed tax changes and the short time line available for consultation.

But a look back shows the Liberals have been signalling a move in this direction for quite some time.

The Trudeau team and the 1 per cent

Shortly after Justin Trudeau became Liberal leader in 2013, the party took considerable interest in the international debate over income inequality. The Occupy Wall Street protest movement in the United States drew attention to the gains of the top 1 per cent of income earners, highlighting the success of the rich elite during a prolonged global economic downturn. The populist movement gained an academic champion in the form of French economist Thomas Piketty, who released an English version of Capital in the Twenty-First Century in 2014 that quickly became a surprise bestseller. The book's title was a wink at Das Kapital, the 1867 critique of capitalism and globalization written by economist and philosopher Karl Marx, who had previously published the Communist Manifesto.

Dr. Piketty's book highlighted the historical role that income from capital – as opposed to wages – played in allowing the rich to expand their wealth at a faster pace than economic growth. It concludes by proposing a global tax on wealth.

The Economist magazine called Dr. Piketty "the modern Marx," praising his research but discounting his recommendations.

"Mr. Piketty's focus on soaking the rich smacks of socialist ideology, not scholarship. That may explain why Capital is a bestseller. But it is a poor blueprint for action," the Economist wrote.

Team Trudeau had a different reaction.

Chrystia Freeland, who is now Canada's Foreign Affairs Minister, called the book a "must read." Ms. Freeland, a former financial journalist who contributed to Mr. Trudeau's economic platform, had explored many of the same themes in her 2013 book Plutocrats: The Rise of the New Global Super-Rich and the Fall of Everyone Else.

In that book, Ms. Freeland describes income earned on capital as "getting rich in your sleep." While Ms. Freeland's book focused on examples of egregious consumption by the global elite, Canadian data does not fit easily into the narrative of growing inequality.

A 2015 study by the Parliamentary Budget Officer found inequality had worsened in Canada between the mid-1970s to the mid-1990s, but has largely stabilized since. Nonetheless, the writings of Mr. Piketty and some Canadian academics gave the Liberals a policy foundation for their successful tax-the-rich campaign in the 2015 election. Politics were also at play.

"There's nothing better for a populist than a rich guy raising taxes on rich guys," Mr. Trudeau's principal secretary Gerald Butts was quoted this summer in the New Yorker as telling Steve Bannon, the then-senior adviser to U.S. President Donald Trump.

The 2015 election campaign

The corporate tax structures of small businesses have long been on Mr. Trudeau's mind.

"We have to know that a large percentage of small businesses are actually just ways for wealthier Canadians to save on their taxes and we want to reward the people who are actually creating jobs," he told the CBC's Peter Mansbridge during the election campaign.

The Liberal platform said $3-billion a year in new tax revenue could be found in part by eliminating various tax credits "that unfairly help those with individual incomes in excess of $200,000."

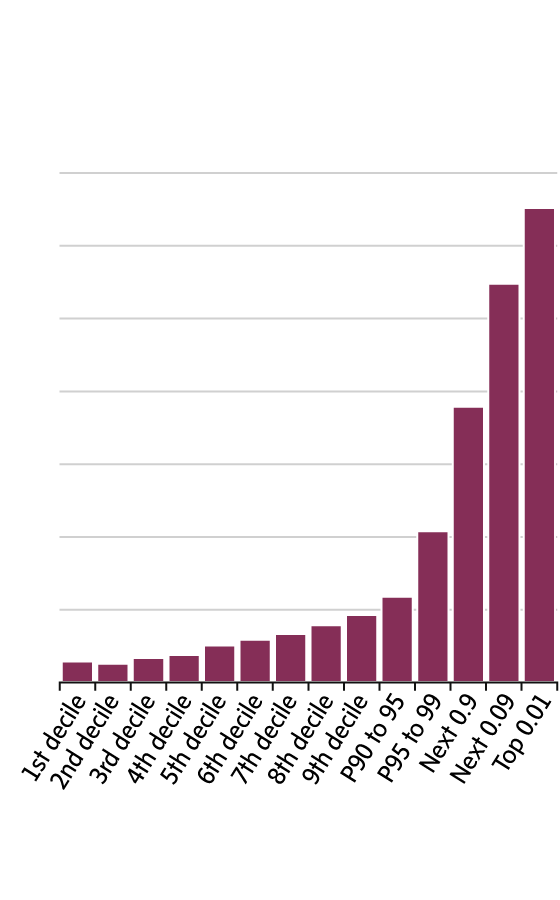

As part of that promise, the platform referenced the research of Michael Wolfson, a University of Ottawa professor who – along with several other Canadian academics – had raised concerns that small business corporate structures are being used by high-income earners to pay less tax. Dr. Wolfson estimated that Ottawa is losing about $500-million a year in tax revenue because of this. He noted that few middle-to-low income Canadians are incorporated. However the higher one is up the income ladder, the more likely they are to have a small business corporation.

Ownership of CCPCs (2011)

Percentage of individual income tax filers owning

more than 10% of the shares of at least one

Canadian-controlled private corporation, by T1

after-tax percentile income group

70%

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

Note: 1st decile corresponds to bottom 10% of after-tax

income earners.

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: WOLFSON, VEALL, BROOKS

AND MURPHY

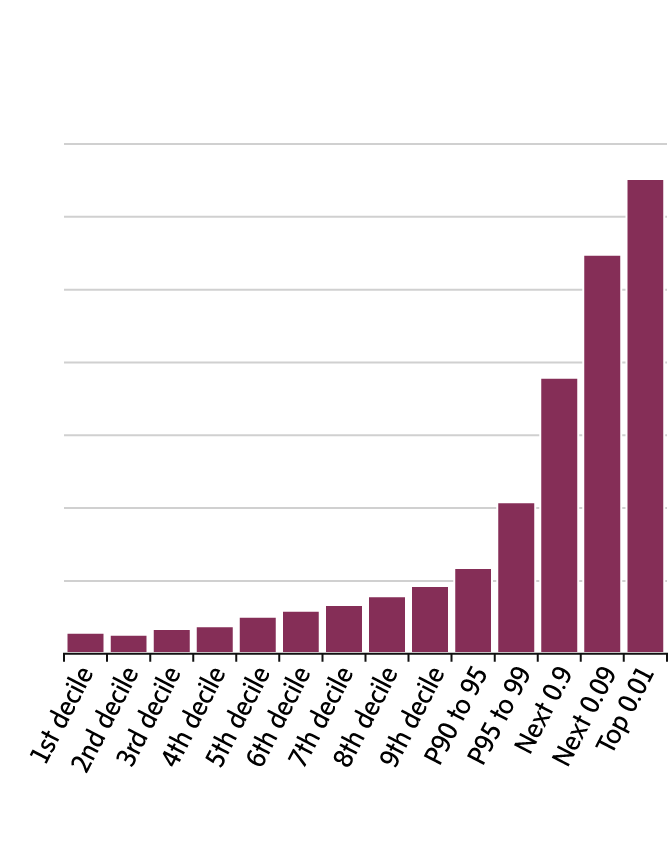

Ownership of CCPCs (2011)

Percentage of individual income tax filers owning more than

10% of the shares of at least one Canadian-controlled

private corporation, by T1 after-tax percentile income group

70%

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

Note: 1st decile corresponds to bottom 10% of after-tax income earners.

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: WOLFSON, VEALL, BROOKS AND MURPHY

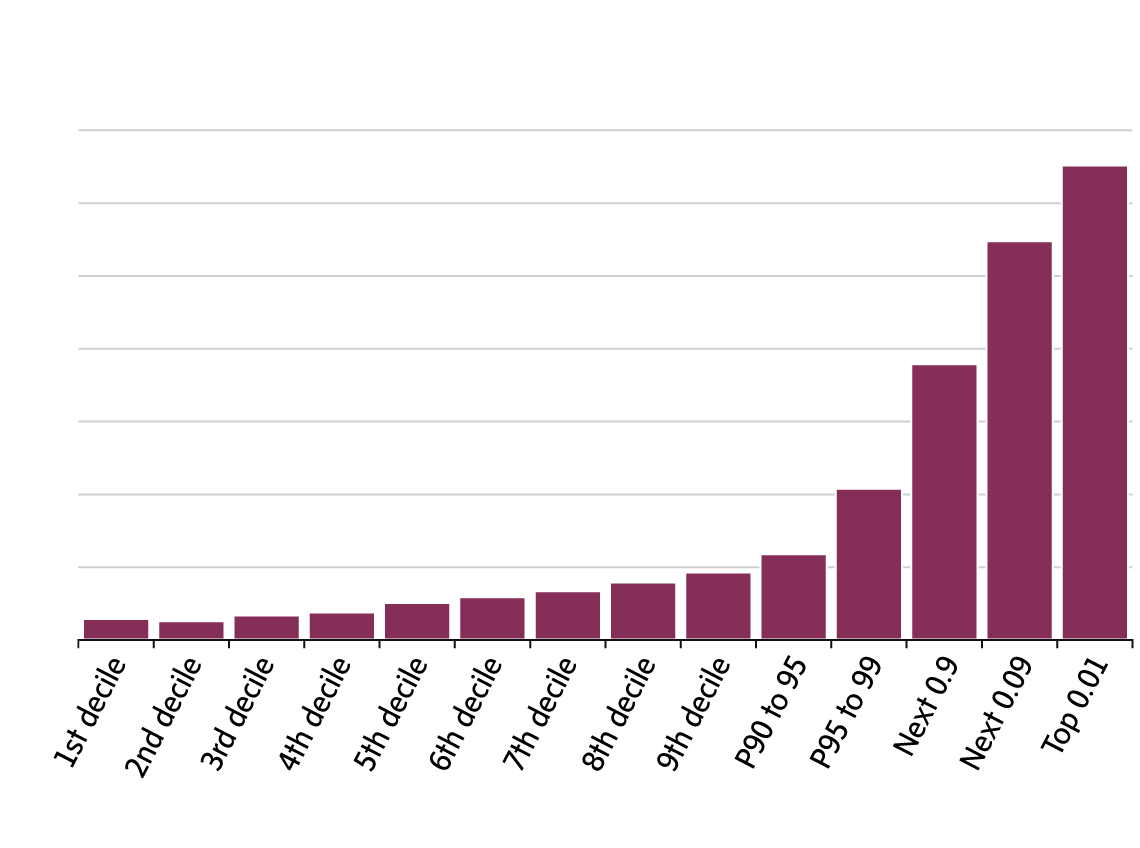

Ownership of Canadian-controlled private corporations (2011)

Percentage of individual income tax filers owning more than 10% of the shares of at least

one CCPC, by T1 after-tax percentile income group

70%

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

Note: 1st decile corresponds to bottom 10% of after-tax income earners.

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: WOLFSON, VEALL, BROOKS AND MURPHY

His work singled out the fact that a corporate structure can allow business owners – including incorporated professionals such as doctors – to pay less tax by splitting income with their spouse. A similar advantage does not exist in the personal tax system, though some income splitting was allowed under the Conservative government.

The Liberals promised to eliminate income splitting for couples on the personal income tax side and the platform reference of Dr. Wolfson's work hinted at an effort to ensure small business corporations can't be used as an income-splitting tool.

(Pension-income splitting for seniors – a measure introduced by the Conservatives in 2006 that costs the government about $1.3-billion a year in forgone tax revenue – is not being touched by the Liberals.)

Dr. Wolfson, who has a PhD in economics from Cambridge, retired as assistant chief statistician at Statistics Canada in 2009 following a public service career that included positions at the Department of Finance and the Privy Council Office.

"Over in this dark corner of the tax system that most people don't know exists and most people don't understand how it works, income splitting has been going on for decades," Prof. Wolfson said in an interview with The Globe in 2015 following the release of his findings. "But nobody shines a light on it. Nobody asks what's going on here."

Since the reforms were announced, Prof. Wolfson has publicly defended them in The Globe and elsewhere.

Critics of the proposals – including former Statistics Canada chief economic analyst Philip Cross – accuse the government of relying too heavily on the opinions of Prof. Wolfson and other "academics obsessed with income redistribution," rather than on the real-world experience of small business owners.

The Trudeau government in power

It was the central theme of the Liberal campaign. A new tax on the 1 per cent would pay for a tax cut for the middle class.

The promise proved to be a political winner. The math, however, didn't add up.

Shortly after forming government, the Liberals acknowledged the tax on the 1 per cent would not raise the $3-billion a year required to pay for the promised tax cuts. In fact, the plan would create an annual shortfall of about $1.2-billion.

The tax plan went ahead nonetheless. A new rate of 33 per cent was imposed on income in excess of $200,000. The rate on the middle income tax bracket – covering income between $45,916 and $91,831 – was reduced from 22 per cent to 20.5 per cent.

When combined with provincial taxes, the change pushed the top tax rate to above 50 per cent in several provinces. Critics warned that tax rates above 50 per cent would create an incentive for high-income earners and their accountants to find creative ways of avoiding the new top rate.

The 2016 budget announced that the Finance Department would be spending the next year reviewing Canada's system "with a view to eliminating poorly targeted and inefficient tax measures."

The 2017 budget

Finance Minister Bill Morneau's 2017 budget clearly signalled that changes were coming. The budget said a year-long internal review of the tax system – led by Finance Canada with help from a panel of outside experts – had found issues with the way some Canadians are using the small-business tax structures, officially known as Canadian Controlled Private Corporations.

Over the course of a few paragraphs, the budget said the government was looking at three specific practices related to incorporated small business – income sprinkling, passive investment and the treatment of dividends and capital gains – and would be releasing a paper later in the year to explain the issues in more detail and to propose policy options.

"A variety of tax reduction strategies are available to these individuals that are not available to other Canadians," the budget stated. "The government is therefore further reviewing the use of tax-planning strategies involving private corporations that inappropriately reduce personal taxes of high-income earners."

During an interview with The Globe and Mail in his Parliament Hill office shortly after the release of the 2017 budget, Mr. Morneau was asked how he connects with average Canadians given that he is a member of the 1 per cent, as is the Prime Minister.

Mr. Morneau said that his time at Morneau Sheppell, a human resources consulting company, gave him insight into the concerns workers have about their future and their pensions. Meanwhile, outside of his role as an executive, he noted that he volunteered at Toronto's Covenant House and St. Michael's Hospital, where he worked with people struggling with poverty and mental health issues. He also worked with refugees in Africa, founding a special school for Somali and Sudanese girls.

In addition to that, Mr. Morneau said he relies on door-knocking and the extensive prebudget consultations conducted by his department.

"My work outside of my business has given me context in those areas, and of course that's amplified what I've seen inside my business: the kinds of stresses and challenges that people are facing on a day-to-day basis in their work lives," he said.

The reveal

On a hot Tuesday in July, Mr. Morneau held a news conference with his deputy minister and parliamentary secretary at the National Press Theatre across from Parliament Hill. He released two pieces of draft legislation and a policy paper, all of which would be subject to a 75-day comment period.

"Since 2001 the number of Canadian controlled private corporations has increased by 50 per cent. In some industries the number of these corporations has more than doubled. This is a worrying trend," said Mr. Morneau. "While there are some good reasons for this increase, in other cases some people may be paying less than their fair share for the essential services that Canadians rely on."

The Minister then walked through the details of the government's proposals.

"What we're really doing is closing down loopholes that people are currently using at an increasing pace to give themselves a lower tax rate," he said.

But some of his language in that news conference set the stage for future problems.

Tax lawyer Karen Stilwell panned the Minister's use of the term loopholes in an analysis piece following the announcement.

"I can only infer that this language is intended to obfuscate and to persuade the public that its proposals are virtuous and just while inviting as little critical thought as possible," she wrote. "It is a linguistic tactic that makes those of us now crying foul seem the defenders of loophole abuse."

Weeks later, as the issue took on more prominence, Liberal MP and House of Commons Finance Committee chairman Wayne Easter would echo those concerns.

"The communications was just god-awful," he told The Globe and Mail in an interview. "The communications made people feel that they were being accused of abusing the tax system."

The political reaction has also turned personal. The Conservatives and NDP are questioning why the proposed changes do not affect family trusts. Both Mr. Trudeau and Mr. Morneau are the beneficiaries of family trusts. They also hold various numbered companies.

At the time of the July 18 announcement, Mr. Morneau said he has deliberately avoided any attempt to find out how the changes would affect him personally.

"I've done that on purpose because I want to make sure that the system is fair. I don't want to consider my personal situation," he said. "My expectation is that these changes over the long term will mean I'll end up paying more tax."

The sales job

After the internal criticism of his approach to communications, Mr. Morneau is now engaged in an all-out effort to sell his plan. He has been meeting with his critics in the business and accounting world and has suggested he's open to changes.

"It's a consultation because we want to hear what your point of view is," he told a conference of accountants in Ottawa on the first day of Parliament's fall sitting. "But we're not going to step back from our objective. It's what we ran on as a government."

The government responds

Just two weeks after the consultation period closed, Mr. Morneau delivered a week-long roll-out of policy responses to the criticism his proposals faced.

On Oct. 16, the government announced that it will be lowering the small business tax rate from 10.5 per cent to 9 per cent by 2019. It also announced that it would better define when income sprinkling is allowed and said those rules would not apply to the lifetime capital gains exemption.

On Oct.18, the government said an incorporated business will be allowed to receive up to $50,000 a year in passive investment income – equivalent to a 5 per cent return on savings of $1-million – under existing tax rules. Passive income above that amount would be subject to higher taxes.

The next day, Mr. Morneau announced he announced that the government will not move ahead with the draft legislation related to dividends and capital gains.

It is not yet clear when the government will move ahead with its revised plans on income sprinkling and passive investments.