Merchandise based on the characters has become one of the hottest sellers in the toy aisle.Scott Cawthon

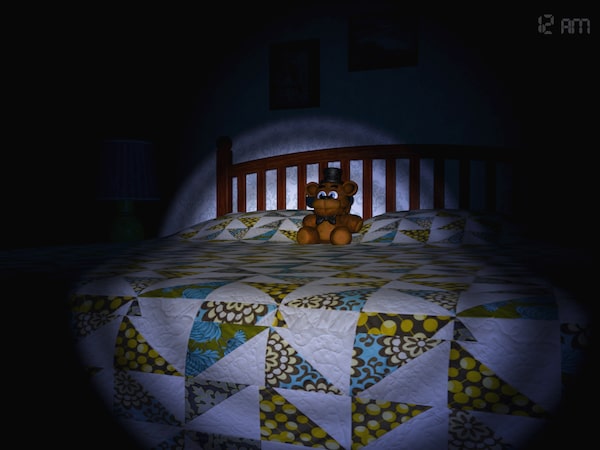

A young child is tucked cozily in bed for the night. But instead of drifting off to sleep, he hops out of bed, checking his closet and behind two hallway doors with a flashlight. Suddenly, a monster jumps out and kills him.

Game over.

Parents might be interested to learn that Five Nights at Freddy’s (often shortened to FNAF) is a downloadable survival-horror video game. It’s not particularly bloody or gross, but FNAF has been engineered to scare the living daylights out of players. Much of the game, which can be played on Windows, Apple and Android devices, is also specifically designed to engage a young audience. The setting of the first version of FNAF (there are six) is a haunted pizza parlour similar to the Showbiz Pizza or Chuck E. Cheese child-focused chains. Meanwhile, its cast of odd-looking cartoonish animal mascots – with such names as Freddy Fazbear, Bonnie the bunny, Chica the chicken and Foxy the fox – are easy to develop into merchandise. Kids who may have yet to hear about FNAF are being drawn into the brand when they see these cuddly characters in the toy aisle, making the game itself more popular with children as young as 6 or 8, even though it’s rated only suitable for those 12 and up.

FNAF’s large following is perhaps most evident on YouTube. It’s been highlighted by scores of channels and videos – sometimes showing adults or children playing the game, sometimes just talking about it or editing together all the “jump scare” moments – which have collectively racked up more than 30 billion views according to Striker Entertainment, the California-based company responsible for the game’s retail strategy. FNAF’s success has also prompted a film development deal with Blumhouse Productions, the producers behind the low-budget horror smash-hit Get Out.

Meanwhile, merchandise based on the characters has become one of the hottest sellers in the toy aisle. Freddy first showed up in 2014 and the first products began hitting shelves in 2015. They have since clambered into the minds of children without the help of traditional mainstream media and toy biz players thanks to YouTube and early digital fans.

While toys are often viewed as just a way to monetize an existing fandom or product, researchers say merchandise can also push a child to seek out the underlying content behind the brand. And when that merchandising is done effectively, says Colleen Russo Johnson, Co-Director of the Ryerson Children’s Media Lab, it can help a brand become a household name.

For 25 years Todd McFarlane, the Canadian comic-book artist and entrepreneur behind McFarlane Toys, was a small player in the hyperrealistic collectible and action figurines market working with big brands such as the NFL, The Walking Dead and video games such as Mass Effect and Destiny. In just a few years FNAF’s “lightning in a bottle” upended his business, the construction toy sets (Lego-style blocks that depict FNAF scenes) are his biggest-selling brand ever and have already grown to become 50 per cent of his business.

He says he has never seen a horror-genre product succeed among children in this way. “Here’s what [FNAF creator Scott Cawthon] did, intentional or not: Most people who do creep cross a line and make it violent and stuff like that,” McFarlane says. “He brought all the stuff that you and I would call scary and creepy and horror and put it in a format that was palatable to parents. It’s not Freddy Kreuger … It’s these cute little fuzzies.”

A still uploaded to the Steam community.Scott Cawthon/Scott Cawthon

In fact, Funko Holdings LLC, which is the biggest money maker for FNAF, says the only toys that sell better are the massive brands controlled by Disney. FNAF also attracted a whole new demographic to Funko, which mostly sells collectibles to pop culture-hungry adults: young boys between 8 and 12.

But the ubiquity of the toys, and the way they’ve drawn young players to the game, raises questions about FNAF’s frightening content, and its effect on children.

Teresa Lynch, an assistant professor with the School of Communication at Ohio State University who has been studying fear engendered by video games, says there are critical differences between the way children and adults process games and fear.

“Very young children cannot be told that what they see online isn’t real … To them, it’s as real as anything that’s happening off screen,” she says. Studies suggest children under the age of six would fit into that category, but that the process of developing an abstract sense of reality continues until they are 10 or 12.

“I usually have this conversation with conservative moms,” says McFarlane, who is an outspoken libertarian-leaning artist and businessman. “There is not one medical report that any medical doctors agree on, that if you show make-believe to well-adjusted human beings it will distort them. That report does not exist. You know how I know it doesn’t exist? Because if it did every mom and conservative churchgoing person would know it chapter and verse and they could throw it back in our face.”

Researchers disagree, and say there is plenty of evidence that media can have lingering effects on children.

“Kids are extremely vulnerable to fear, and it’s often difficult to alleviate once it’s there,” says Joanne Cantor, a retired psychologist and researcher from the University of Wisconsin who remains one of the leading scholars of the effect of fear on children. Reacting to the example of FNAF’s bedroom game, Cantor was aghast.

The ubiquity of the toys, and the way they’ve drawn young players to the game, raises questions about FNAF’s frightening content, and its effect on children.Scott Cawthon

“If you can create a video game where you put a child in their most regular and supposedly safe environment, and turn that in to the most vulnerable one? That’s the worst thing you can do,” adds Cantor, who says studies have found that just a few minutes of terror, from for example watching a horror movie, could create a powerful and persistent fear response in children. “Kids can have nightmares and sleep disturbances that last literally for years … Not being able to sleep has tremendous emotional and physical negative outcomes for kids.”

“[Terror is] an extremely expensive state to be in, in terms of the resources in our body,” Lynch says. “Short-term memory building can be impaired and it exhausts a lot of cognitive processes.”

There are also small hints that retailers are struggling with how age-appropriate the toys are. Funko created a vinyl collectible for a decayed and eye-less version of Spring Trap (a bunny-like figure) which is punctured by unidentifiable wounds and what looks like blood (but could be red wires) leaking out of some of the holes. On Toys R Us’s site, Funko’s suggested audience is listed as eight years and up, while the retailer urges 14 and up only.

Of course, there’s really only one gatekeeper that matters in the end.

“Mom, dad, if you don’t like the product, do your job, be a parent, don’t bring it into your house. Done,” McFarlane says.

Shane Dingman

Shane Dingman