Vladdeep

When I’m weary of the more anxiety-inducing challenges of everyday living, I like to grocery shop. Not the kind undertaken by necessity or routine, but the mindless aisle-wandering that allows for a different kind of focus: on what we might eat in the immediate future.

Once adulthood is achieved, most of us must go for groceries (or convince someone to do it on our behalf), regardless of age, culture and income level. And because we all need to eat all the time, there’s no getting around picking up the essentials with some regularity.

Except that now there is. Over the years, neighbourhood markets have been slowly nudged out by retail giants and big box stores such as Walmart, Costco and Loblaws, which are now themselves being squeezed by Amazon, the retail behemoth leading the charge in the realm of online grocery delivery, even in Canada.

Online shopping and home delivery appear to be the new progression of shopping in general – retail e-commerce revenues reached almost US$40-billion in Canada in 2018, exceeding most predictions, and delivered meal kits have grown into a $120-million industry. In December, Loblaw Companies Ltd., Canada’s largest grocery retailer, launched a new loyalty program modelled after Amazon Prime. It aims to have 100,000 of its 16 million PC Optimum members pay $9.99 per month or $99 per year for complimentary e-commerce grocery pick-up, free delivery of joefresh.com, shoppersdrugmart.ca and pharmaprix.ca online orders, and other bonuses. As competitors offer incentives to earn loyalty and entice customers into the habit of having their groceries delivered or packed to pick up in the parking lot, consumers are at risk of losing the best parts of the real-life grocery shopping experience.

Tara Austen Weaver, a friend and author, recently confessed on Facebook that she loved going to the grocery store during the holidays. Not for the festive displays, but to take in the collective energy of people preparing to feed each other. Similar to the arrivals area of the airport, there’s an air of anticipation – the prospect of something good to come. “The stores are full of people who don’t usually do the shopping and they’re calling home to check if they’re getting the right thing, or taking calls from home with last-minute requests,” she wrote. “And often they are multigenerational family groups and it all just reminds me of the lengths we go to to be with and do right by our people, and that makes me happy.”

The thought of such a common practice reduced to yet another click makes me nostalgic for the shared ritual of grocery shopping – the modern-day version of hunting and gathering to feed ourselves and our families alongside our neighbours. Even when stores aren’t engorged with holiday shoppers, I find comfort in the familiarity of the aisles, in the opportunity for casual chit-chat with a butcher or cashier – particularly those you recognize, even get to know – and a fleeting sense of kinship between myself and whomever else happens to also be pondering yogurt options in the same junction of time and space.

“Social isolation is the public health risk of our time,” psychologist Susan Pinker said in her 2017 TED Talk, in which she cites a study that found social integration at the top of a list of lifestyle factors that had a positive impact on longevity, beating out quitting smoking, getting regular exercise and maintaining a healthy weight. Research has consistently shown, across generations, populations and disciplines, a direct correlation between social interactions and a sense of well-being, and that these seemingly small, regular personal connections are as critical to good health and longevity as deeper, more intimate relationships.

On a recent Saturday afternoon at Bridgeland Market in Calgary, a modernized yet old-school neighbourhood grocery that occupies more than 2,000 square feet in a 1912 brick building and sells everything from prepared meals to toilet paper, I roamed the aisles as regulars chatted about their holidays and cooed over each others’ toddlers. The resident cheese curator leaned over the counter to offer bits of runny French vacherin. I took some home, along with a wedge of parchment-wrapped cultured butter, having been romanced by personal stories of the co-owner’s travels through France. Although I ran in for cheese, I was tempted by piles of locally made fresh corn tortillas and reminded while watching the butcher truss and stuff a crown roast of pork that I could probably manage the same for my next family gathering.

Even at larger, less nostalgic stores you tend to stumble upon random meetings between people who haven’t had an occasion to see each other in ages, catching up over half-filled carts tucked nose to nose to one side to allow other shoppers by. There are the small conversations you can’t help but overhear – the couple deliberating over pasta shapes or wondering aloud what the difference is between white kidney beans and the cannellini beans called for in a recipe. There are solo and group shoppers, and kids begging for sweet cereal strategically placed at their eye levels. And the checkout line allows a peek at how other people live, their purchases spread out on a shared conveyor belt: Recently, a woman in front of me was buying turnips and Gravol, while the guy behind had a box of ice cream bars and a tower of tinned cat food. Who needs reality TV?

Besides the small human interactions inherent in the physical grocery shopping experience, which can be significant social events for some retirees and people who live or work alone, cruising the aisles allows the shopper to be inspired by the thousands of products on store shelves, to be open to impulse buys and consider alternative or sale options. Clicking photos to fill an online cart is formulaic, less emotionally charged and more likely to reinforce old buying – and by extension – cooking, habits, particularly when there’s space for only so many selections appear above the fold (most likely taken up by food brands with marketing budgets to secure this prime real estate), and there’s the option to commit to digital memory a list of staples to automatically re-order each week. (Watch Big Food companies capitalize on this opportunity to seal the deal on repeat shoppers by getting their products into your weekly virtual cart.) Gone is the chance to hand-pick small Brussels sprouts or not-so-green bananas, and to learn how to smell and squeeze to select a pineapple or avocado at just the right stage of ripeness.

While we may appreciate being relieved of the need to push a cart, stand in line, and even load groceries from store to car to house, regular activity is something the majority of us need more of. Convenience is a popular marketing angle – as, ironically, is good health – but as always, it comes with a cost.

Not-so-little shops around the corner

1800s

Grocery stores were “basically convenience store size,” says George Condon, consulting editor of Canadian Grocer. With all the goods stored behind the counter, customers would request items from a clerk, who would gather the items.

1916

Clarence Saunders opens the first self-serve grocery store, called Piggly Wiggly, in Memphis, Tenn. The concept was so successful that most other grocery stores changed to self-serve by the 1930s.

1917

Ida Steinberg opens her eponymous grocery store in Montreal. Steinberg’s would open Quebec’s first supermarket in the 1940s.

1929

Safeway opens its first five Canadian stores in Manitoba.

1930

Michael Cullen opens the first “supermarket,” King Kullen, with different departments for meat, dairy, baked goods and other items in Queens, N.Y.

1937

Sylvan Goldman, owner of a supermarket chain in Oklahoma called Humpty Dumpty, introduces the first shopping cart. It was made from a metal frame that held two wire baskets. The carts were called “folding basket carriers.”

1949

Loblaws, founded in Toronto in 1919, introduces “healthfully cool equipped air-conditioning” in its new “super market” stores.

1950s

Chain stores begin proliferating. “There were still a lot of independents, but chains grew,” Condon says. “They bought out independents and they opened more of their own stores.” Grocery store flyers, designed to lure customers with deals, also became popular during this period.

1960s

Shopping malls anchored by grocery stores spread throughout North American suburbs.

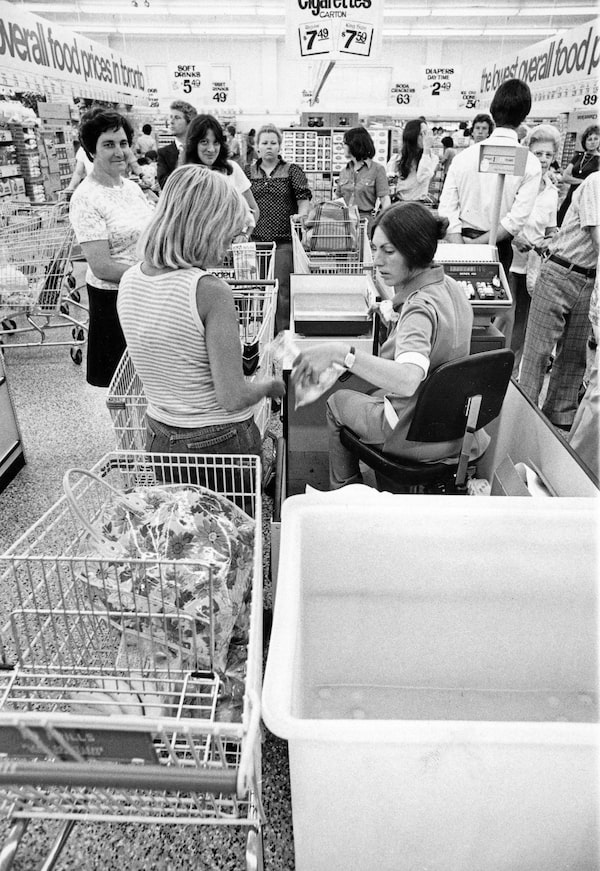

Shoppers buy groceries at Loblaws' newly-opened 'no-frills' supermarket on July 5, 1978.STEVE PATRIQUEN

1979

The first Real Canadian Superstore opens in Saskatoon.

1980

The first Whole Foods Market opens in Austin, Tex. There were fewer than half a dozen natural food supermarkets in the United States at the time, according to the company. The first Whole Foods in Canada, in Toronto’s Yorkville neighbourhood, opened in 2002.

1986

The first Price Club in Canada opens in Montreal. Sol Price launched Price Club, the first membership-based store, in San Diego in 1976. Customers were charged a U.S. $25 annual membership fee to buy bulk items at a discount price in what was essentially a warehouse.

1990s

Grocery stores begin experimenting with technology to appeal to increasingly time-starved customers. Longo’s launched a program in Toronto called Freshness-to-Go, that allowed customers to phone or fax orders to be picked up in store. Grocery Gateway, a pioneer of online grocery shopping, launches in 1999.

2006

The first Canadian Walmart Supercentres, combing a full-scale supermarket with general merchandise, open in three locations in Ontario, in Stouffville, London and Ancaster. The company’s original Supercenter opened in Washington, Mo., in 1988.

2014

Loblaws launches a “click-and-collect” program, allowing customers to select items online and pick them up at the store’s front entrance at set time, doing away with the need to get out of the car.

2018

Amazon opens its first Amazon Go store on its Seattle campus. The fully automated grocery store promised “no lines, no checkouts, no registers.” Customers simply scan their Amazon Go app, pick the items they want and walk out, with the app tracking their virtual shopping cart.

– Dave McGinn