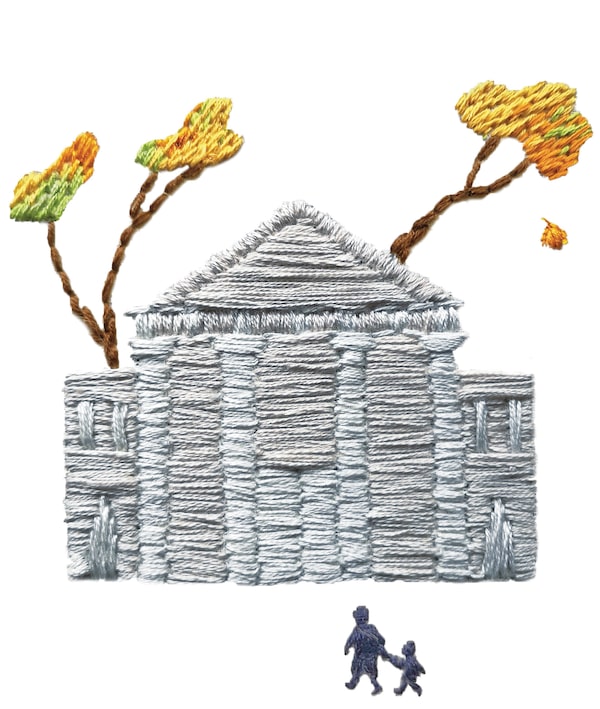

Illustration by Ashley Wong

On my downtown Toronto block, spring sneaks up on us. The undetected hole in my boot was proof against the snow all winter long, but it’s powerless against the meltwater lakes of the local crosswalk. The overnight freeze/thaw cycle leaves street-parked cars sunk into troughs of ice, studded with shattered plastic from futile attempts to dig them out with snow-scrapers.

But, every year, there’s one afternoon where I can finally pry open the door to the backyard shed. I grab the bucket and supplies I carefully stowed in garbage bags last year, and holler to the kids that it’s time. We pile out the door to the front yard, drill a small hole in the great big silver maple at the edge of the sidewalk and gently hammer home the tap, called a spile. We hang the metal bucket on a hook, and fasten the lid over top to keep out leaves and the fast-food cups of passersby for whom any concave surface seems like a trashcan.

For years now, each spring, my kids and I tap the city-owned tree in my front yard to make maple syrup. Silver maples are not like the more prolific sugar maple of professional producers, but they still makes a mighty fine product. We pour each pail of the thin sap into a cast-iron pot on the front porch, and, when we have enough, boil it down on the kitchen stove.

I’m aware that while I use this to connect myself back to long-held traditions in this land, I’m producing as much irony as I am syrup. I ordered my spile and bucket online, delivered to my doorstep by next-day mail. It takes three or four hours spending pricey natural gas on my biggest burner to boil 40 litres of sap down to one litre of end product. And, if you add in in the three fancy pots I’ve destroyed by misjudging the final moments between perfect syrup and burnt sludge, I’m probably paying $50 a litre. It’s ludicrous to even try.

But the process, still, seems like magic. Like something from nothing. In the same way that vegetables from the garden seem like they’re free, despite hours of effort and hundreds of dollars at the gardening store – getting something precious without directly purchasing it is a powerful novelty in the modern age. I’ve heard someone describe libraries as the last place in the world you can sit in the winter without having to buy or believe in anything. Syrup from the tree feels like that – anti-capitalist, outside of the world of commerce.

I’ve spoken to the city-paid arborist when he inspected our tree a few years ago, and he personally had no trouble with the process. He declared our tree a grand old dame, more than a hundred years old but still healthy. He said she’d still be standing when all of us were long gone. The roots, he thought, must stretch a few blocks in all directions – something I can attest to, as I’ve watched neighbour after neighbour get their yards dug up when tree roots pierce the old clay drain pipes.

But this is the last year we’ll be able to have our mid-city sugar bush: A neighbour phoned the law on us. A city bylaw officer stopped by and wrote us up, threatening a fine if we kept up the tradition. Apparently, their policy is to disallow tapping or anything else that might harm a city tree. They say that in the forest, a tree has access to good-quality soil and adequate rainfall that help them heal from the wound of a spile; in the city, trees – like the rest of us – are more stressed out by the concrete and traffic.

But it makes me wonder: What is a city tree for? We carefully grow trees outside of their supportive forest environment for a purpose – to bring a bit of joy into the built environment. We cause them stress in order to reduce our own. This beloved tree rustles in the breeze all summer long, and I sit on my porch and appreciate its presence here in this harsh world of pavement and noise. Sap is one more thing I’d been harvesting from it, to share a little joy. And it works. I’ve watched generational waves of toddlers on my street entranced by the bucket as they walk to school. With a parent’s encouragement, they gingerly lift the lid each day to check on the progress over the course of the week. I’ve left cups out so kids can taste the watery sap directly, fresh from the tree. Universally, people on the street are amazed at the idea that this is even possible – we’re so trained to believe that industrial scale is the only scale at which we can make anything.

I get the conundrum the city is in. Cities operate at only two levels: everyone and no one. Not all trees are healthy enough to be tapped. If the city allowed tapping, they’d have to worry what it would be like if everyone did it. And so, they make it that no one can. But these policies can kill the neighbourhood cohesion, the resiliency, that we establish blue-ribbon commissions to build. Our tree is next to the “Ball and Hockey Playing Prohibited” sign on the block – a sign which, when gleefully ignored by the local kids, sparks the informal neighbour-to-neighbour interactions city builders dream of.

But you can’t fight city hall. The city website tells urban syrup-seekers we can’t tap our trees. They tell us to visit one of the city-owned conservation areas to get our fix of the sugar-bush tradition. Joni Mitchell must have been prescient: They took all the trees and put’em in a tree museum, and they want to charge me a dollar-and-a-half just to see ’em. So, I’m raising money to pay the admission fee. For sale: One spile, one bucket, one lid; slightly used and well-loved.

Richard Lachman lives in Toronto.