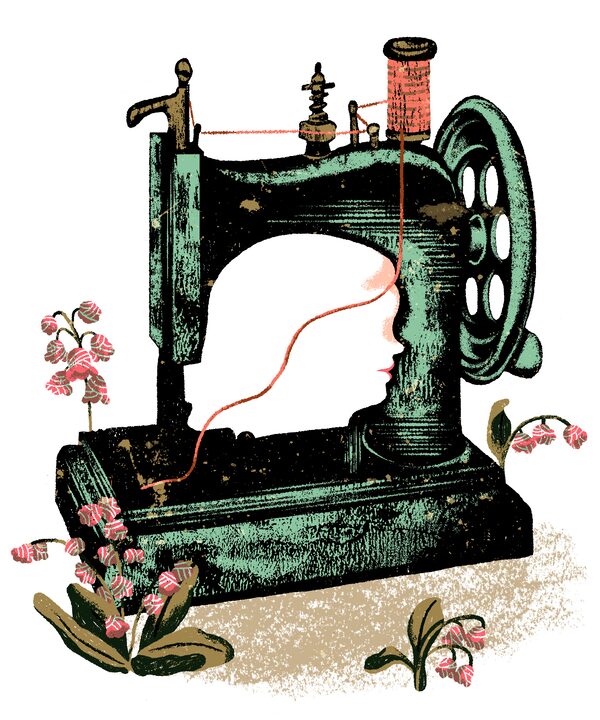

ILLUSTRATION BY RACHEL WADA

First Person is a daily personal piece submitted by readers. Have a story to tell? See our guidelines at tgam.ca/essayguide.

I carried the heavy black case onto the plane. I’d carried it countless times before. I knew that weight, that thick handle, that sharp clicking sound of the silver hinges when opening the case and, once opened, the scent of oil and age. The case and contents had been moved many times before – from Winnipeg to Souris, Man., then Montreal, Edmonton, Calgary, Sarnia and back to Winnipeg.

I was carrying one of my mother’s most treasured possessions. She had passed away not long after the passing of her husband, my father, the love of her life. I was bringing her Singer Featherweight sewing machine home with me.

My mother was born in 1923. She was 20 when she and my father married. He was a pilot in the Royal Canadian Air Force. They waited until after the war to marry and soon moved to Montreal where my father pursued his degree in engineering at McGill University. My mother would have put that machine to use in making clothes for my brother, their first born, and for making curtains, tablecloths and mending. There would always be mending.

The late 1940s through to the late 1960s were my mother’s prime housekeeping years. Housework then was a big job. In 1955 Chatelaine magazine published a handbook called New Household Hints. The housekeeping schedule it presents is an exhausting one. Household hints for every day of the week are listed in vivid detail. The seven-day litany is prefaced with another list of 19 “everyday” chores followed by the admonition to “finish one part of the house before going to the next.” It was isolated demanding work.

Sewing was different. It was a vehicle for self-expression where fabric and pattern came together in a creation that was one’s alone. Fabric stores offered quality wools, cottons, velvets, satins, brocades, eyelets, among others while pattern books presented the latest looks. Time alone at the machine was a period of quiet focus, foot gently pressed on the pedal for that consistent smooth flow of fabric through presser and needle, while hands gently guided the fabric. There was the satisfaction of having found and properly cut just the right fabric for just the right pattern. The pieces all came together.

The Featherweight was portable. My mother’s machine was made in 1945 by the Singer Manufacturing Co. Ltd. in Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu, Que. It had one function, a straight lockstitch, which it did very well but it did something else: It was the sewing machine for the modern woman. It only weighed 11 pounds in its compact travelling case, together with a container of extra parts. The Featherweight could easily be carried to where one wanted to sew then quickly packed up and put away. And it was quiet. The purring hum of the Featherweight is considered its most unique, beloved feature.

When we moved from Calgary to Sarnia in 1959 my mother found a sewing machine repairman who had extensive experience with Featherweights. She spoke of him well, adding she would not hand the machine over to just any repairman. It was a matter of keeping the machine in good repair as one would with a car. She said he often asked her if she would sell it. She said she never would.

When my sister and I were in grade school we made our first sewing projects on that machine later using it in high school to make reasonable representations of what caught our eyes when scrutinizing fashion magazines. There was always some project on the go. I remember my mother making a spruce green boat neck velvet dress for a New Year’s Eve dance in 1965. There is a Kodachrome slide of her in that dress standing beside my father in his tuxedo.

My sister was an excellent sewer and stitched her wedding dress on the machine. In 1968 when our brother came home from teaching in Ghana for two years he brought stacks of vividly coloured hand-printed fabric and multicoloured glass beaded necklaces for my mother, my sister and me. My mother helped me make a floor-length, sleeveless dress from one of the fabrics, which I wore with several of those necklaces.

With my sewing projects there was inevitably a problem I could not solve, and I would call out to my mother for help. She would call back, “I’ll be there in a minute." I can hear her voice now. My mother was a soft-spoken woman. Once by my side – “It’s okay. Let me have a look” – she would carefully assess the problem then show me what to do. I lacked her patience, her soft voice, her calm manner. I still do. “I’ll be there in a minute.” It’s been such a long time since I’ve heard those words.

I know the Featherweight was part of my mother’s life from the early days in her marriage. I don’t know why it was that machine she chose over all the others. I don’t know if it was a gift from my father, or if she saved and purchased it herself, nor why she kept it years after she had stopped sewing. I can imagine. But I don’t know. I’ll never know because I never asked.

Christine Dirks lives in London, Ont.