Weeks of speculative Chicken Little-ism notwithstanding, the sky is not falling.

Turns out that the much-anticipated or dreaded overhaul of the provincial health system unveiled Tuesday by Ontario Health Minister Christine Elliott is eminently reasonable.

As a long-time opposition health critic and Ontario’s first Patient Ombudsman, she knows the system’s flaws well. There are tremendous gaps in care, notably when it comes to mental-health services and long-term care; the care patients receive is excellent, but it is delivered in a manner that is siloed and fragmented, particularly when a patient transitions, for example, from hospital to home care; care is system-driven, not patient-centred; and the bureaucracy is stifling.

In short, the existing health system is not much of a system at all.

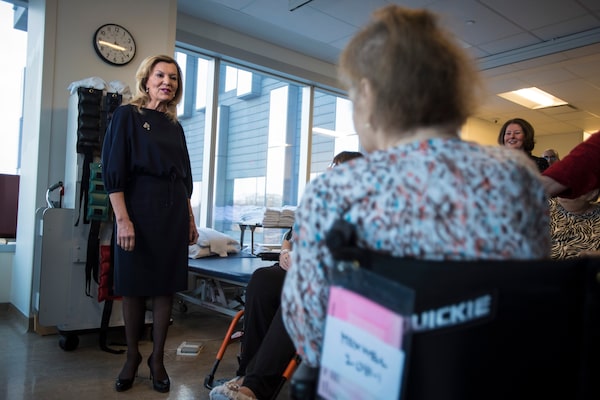

Christine Elliott, deputy premier and Minister of Health and Long-Term Care, chats with patients at Bridgepoint Active Healthcare before making an announcement in Toronto on Feb. 26, 2019.Tijana Martin/The Canadian Press

“The people of Ontario deserve a connected health-care system that puts their needs first,” Ms. Elliott said.

To achieve that goal, the government plans to create a single administrative agency, Ontario Health, that will oversee 50 Ontario Health Teams, which will be responsible for care delivery.

There were a number of leaks about the super-agency plans, and wild claims that the Conservative government was planning mass privatization and big cuts to public services as part of the restructuring. Ms. Elliott said that, on the contrary, the changes will “strengthen our publicly funded health-care system … and that means paying for services with your OHIP card.”

The new centralized structure takes the place of the old, decentralized model consisting of 14 Local Health Integration Networks (LHINs), 76 sub-LHINs and six independent agencies such as Cancer Care Ontario.

A lot of people wonder why Ontario Health is needed if there is already a Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. The role of the ministry is to establish and enforce policy, and to dole out money.

The role of Ontario Health is to oversee the day-to-day operations of a $61-billion-a-year corporation, to ensure care is delivered in the most efficient and cost-effective way possible.

With the planned changes, Ontario becomes the fifth province to create a provincewide, integrated health system, after Alberta, Nova Scotia, PEI and Saskatchewan.

Regionalization was all the rage for a while and now centralization is in vogue. It’s a reminder that there is no perfect structure for delivering health care, but everyone is looking to balance efficiency of scale and flexibility to meet regional needs.

The biggest change in Ontario is one that has not been much discussed. The new Ontario Health teams will be voluntary groupings of hospitals, home-care agencies, mental-health services, community health clinics and more. The OHTs will receive blocks of money and have to figure out the best mix of services to deliver value for money. That approach should be more organic and locally responsive than LHINs, some of which were painfully rigid.

What will happen to the six agencies − Cancer Care Ontario, eHealth Ontario, Trillium Gift of Life Network, Health Shared Services, Health Quality Ontario, HealthForceOntario Marketing and Recruitment Agency – being swallowed up by Ontario Health is not entirely clear.

Ms. Elliott suggested that the successful Cancer Care Ontario model could be scaled up to create a comprehensive strategy for chronic-disease management, which would be excellent.

While there is a lot of rhetoric about patient-centredness, it’s not obvious how patients and families will have more power to shape policies and priorities under the new model.

When governments undertake big changes, the assumption is always that it is a cost-cutting exercise. Ms. Elliott insisted that is not the primary driver but she is certainly aware that a similar centralization exercise in Alberta resulted in an estimated $600-million in savings and some long-term efficiencies.

Read more: Alberta Health Services has become a joke

Doug Ford needs to rein in Ontario’s bureaucratic health-care mess

Alberta’s health-care administration costs are 27 per cent below the national average; Ontario’s are 30 per cent above the national average.

Alberta’s experience is instructive. When Alberta Health Services was created 10 years ago, it was done in a slapdash, ham-fisted way, and health-care providers and patients suffered from the upheaval.

It is good to hear Ms. Elliott say that Ontario’s overhaul will be implemented gradually. It will be important, too, for the province’s political masters to keep their wits about them.

When you undertake major changes, there will be hiccups and failures, and that’s okay. In Alberta, the non-stop political second-guessing was destructive and it took a long time for AHS to find its way.

Is care better in an Alberta with a centralized health system than one with a decentralized health system? Honestly, it’s impossible to say.

But a key lesson from Alberta is that what matters most is stability. Constant rejigging of structures serves no one.

Ultimately, it doesn’t matter whether a health system is centralized or decentralized, or whether the administrative agency’s name is LHIN or OHT. What matters is that there are clear lines of authority and accountability, and a system that facilitates rather than inhibits the delivery of quality care.

André Picard

André Picard