In the aftermath of six tornadoes sweeping through the Ottawa-Gatineau region last Friday, injuring about a dozen people and leaving tens of thousands without power, Canadians are left wondering what the chances are of such weather events happening in their cities across the country.

Neighbourhoods in the Ottawa-Gatineau region turned chaotic last week, with trees crushing roofs, vehicles tipping over and an entire row of hydro poles toppling down on a main thoroughfare. The twisters brought winds that reached 265 kilometres an hour, according to Environment Canada.

Here’s a look at the conditions that lead to tornadoes and how prevalent they are in Canada.

What are tornadoes?

A tornado is a cycle of air that is in contact with both the surface of the earth and a cloud, usually a cumulonimbus cloud (a towering vertical cloud formed from water vapour carried by powerful upward air currents) or, in some cases, a cumulus cloud (a low-level cloud with a flat base). Tornadoes often look like a funnel and can have wind speeds ranging from around 180 km/h to around 400 km/h. Most tornadoes last less than 10 minutes, but can be as long as 40. Their strength is classified on the Fujita scale, a rating system that looks at the storm’s wind strength.

How do tornadoes form?

Tornadoes form from strong thunderstorms. In Canada, conditions that can create a tornado involve warm, moist air travelling up from the U.S., which then combines with cool air from am existing storm. As the airs mix, they create an instability and an updraft, which is strong winds pulling toward the clouds. As the winds pick up speed, they turn vertical and begin to rotate like a tube. The tube stretches and becomes like a giant vacuum, sucking air up and away.

What is the Fujita scale?

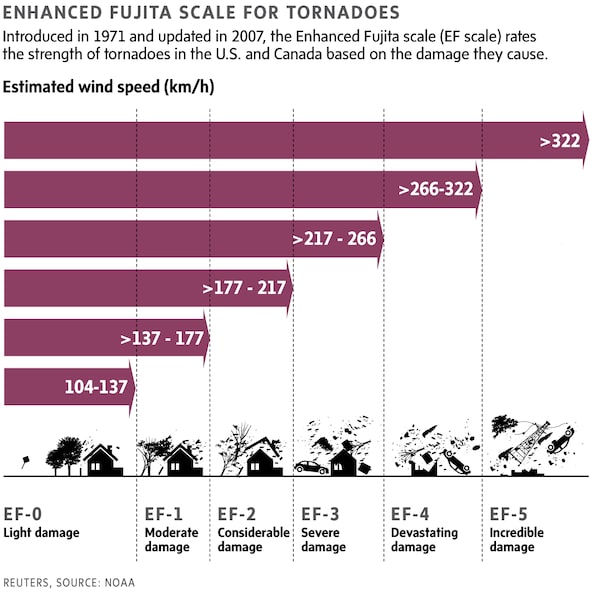

The Fujita Scale, also known as the F-scale, ranks tornadoes on a scale of 0, little to no destruction, to 5, being the most destruction. The scale was used until April, 2013, in Canada, when it was updated with the Enhanced Fujita Scale (or EF-scale), to account for more accurate matches between wind speed and the tornado-caused damage. The lower limit on wind speeds were raised, and the upper limit for the strongest winds was eliminated (previously, the cap was around 510 km/h for an F5 tornado, but now, an EF5 is any storm with a wind speed greater than 315 km/h).

Where and when do tornadoes occur in Canada?

On average, Canada has around 62 reports of tornadoes every year, according to Environment Canada. They commonly occur in southern Saskatchewan and Alberta as well as through southwestern Ontario.

The Ottawa-Gatineau tornadoes were the most recent of 33 tornadoes reported in 2018. One tornado, which hit Manitoba in August, was an EF4 with winds up to 310 km/h. The storm reached a width of around 870 yards and remained on the ground for at least 20 minutes, according to Environment Canada. It led to one fatality, a man in his 70s.

Tornadoes typically occur during the late spring and summer months, and decline in September. According to David Sills, a severe weather scientist with Environment Canada, they aren’t common at this time of year. “Once in a while, we usually see them in the fall, but this is a pretty strong and large event for this late in the season.”

Mr. Sills said tornadoes can happen at any time when the “ingredients come together.” Last week, the Ottawa-Gatineau neighbourhood experienced lingering summer heat and humidity. As recently as this week, on Tuesday, there were tornado warnings in the Windsor region in southwestern Ontario, but we should now see such weather begin to taper off.

Mr. Sills, who is currently working on the development of tools and techniques to track storms, said our ability to identify tornadoes has improved, which is one reason we’re seeing an increase in documented tornadoes.

Canada does not have an established tornado-prone zone, like the U.S.'s Tornado Alley. But tornadoes tend to occur in the southern Prairie provinces (southern Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba) and southern Ontario into southern Quebec. According to Mr. Sills, the southern part of Saskatchewan is the most-prevalent area.

Shelby Blackley

Shelby Blackley