Photography by Studio Le Quartier

“I hope they don’t view me as ‘that billionaire from Canada’,” says Canadian billionaire Lino Saputo Jr.

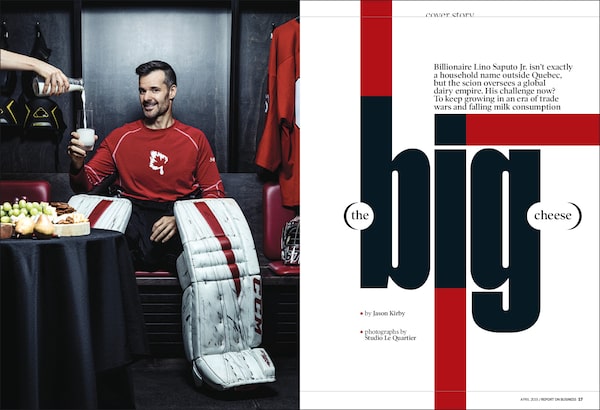

Saputo, CEO of the giant cheese, milk and yogurt company that shares his name, is sitting in the private locker room he installed in the personal hockey arena he built next to the luxury auto club he owns in Montreal. It’s literally and figuratively as far away from the world of Australian dairy farming as you can get. Nevertheless, the “they” he’s referring to are farmers Down Under.

Saputo has been spending a lot of time in Australia lately. Last year, his company acquired the country’s largest dairy processor, a farmer-owned co-op called Murray Goulburn. To seal the deal, Saputo spent weeks criss-crossing thousands of kilometres of arid grasslands, making his pitch to farmers at town hall meetings. In some cases, he even drove directly to farms to sit at their kitchen tables and field questions one-on-one.

Which prompted my first question: What must those farmers think when Quebec's richest man—his family's stake in the company is worth $7 billion—shows up on their doorstep?

“Once you get into a conversation with them, and you talk to them openly and honestly, then I think they get away from the billionaire aspect—you know, the idea that, 'Here's this foreigner coming from Canada trying to screw us as much as he can,'” he says. “I put on my pants one leg at a time and eat three meals a day just like they do.”

Were this folksy sentiment to come from any other 0.0001-percenter, it would be about as easy to swallow as sour milk. But Lino Saputo Jr. is a man of contradictions, able to move back and forth between diverse worlds with remarkable ease. In one moment, the impossibly young-looking 52-year-old might be decked out in a shimmering suit and Bono-style glasses for the ritzy launch of a new Rolls Royce model; the next, he’s on the ice in his goalie gear, blocking shots from blue-collar plant workers. He has a fascination with 1980s-era Porsches and maintains a constantly revolving collection of around 40 luxury cars that he stores at his Automobiles Etcetera private auto club (“I buy and sell them—I love the hunt”). Yet his go-to family restaurant is Bar B Barn, a Montreal chicken-and-rib institution that boasts cartoon-animal mascots and where the rib options range from Baby Hawg to Whole Hawg. “Lino is someone who can speak to royalty and then go talk to the janitor,” says McGill University management professor Karl Moore, who regularly invites Saputo to speak to his students.

Increasingly, the polarized worlds Saputo must navigate exist within the dairy industry itself. When Saputo thrust himself into the NAFTA trade fight last summer, breaking ranks with Canada’s powerful dairy lobby to side with American farmers, it was revealing: Saputo Inc. may be a creature of Canada’s dairy cartel, having benefited early on from the protectionism it entails, but its CEO is an insider more than willing to stand on the outside.

Saputo’s disarming manner and blunt honesty have much to do with how the company got to where it is today. While Saputo Inc. has little name recognition outside of Quebec (the company spends very little on marketing), it has quietly grown into one of Canada’s top international success stories. With 62 plants on five continents—in February, the company announced its latest acquisition, the $1.7-billion purchase of U.K.-based cheese and butter maker Dairy Crest—it is among the largest dairy processors in the world, with 15,000 employees. And with expected sales of more than $13 billion this year, 70% of which comes from outside Canada, Saputo Inc. has become a stock market darling. Since Saputo Jr. took over from his father and namesake Emanuele (known as Lino Sr.) in 2004, the company’s shares have soared 680% (including dividend reinvestment), handily topping the S&P/TSX Composite Index’s 173% total return.

But things are far from idyllic in the land of milk and money. The global dairy market is drowning in a glut of milk, while more consumers bypass the dairy aisle. At the same time, a world that seemed to be growing smaller thanks to globalization is now seeing countries turn inward, leading to geopolitical strife and the threat of trade wars. It's all starting to weigh on Saputo's financial results and stock; over the past three years, Saputo's share price has suffered the indignity of merely matching the benchmark index.

Saputo Jr. isn’t sitting still. The recent deal that plunged the company into the U.K. market just a month before Britain’s scheduled exit from the European Union was characteristic of a company built on bold bets. But this is also an important moment. As the third Saputo to run the company after his father and grandfather, he is ever-cognizant of the curse of the third generation. “Rags to riches to rags,” Saputo chimes in, referring to the old adage that the first generation starts a business, the second builds it up, and the third blows it to pieces—a pattern that played out famously with Quebec’s Bronfman clan and its Seagram fortune.

“I've been mindful of that since I started in the business,” says Saputo. “My father's motto, ever since we were kids, was, 'You have to work harder than everybody else because you know all eyes will be on you.'”

Never have more eyes been on Lino Saputo Jr. than right now.

The first rule of dairy club is you do not talk about dairy club.

For close to 50 years, Canada's supply-managed dairy industry, which shields farmers from international competition through a mix of quotas, tariffs and price controls, has defied every effort at reform. All but the maddest of politicians (see: Maxime Bernier) have been cowed by the deep-pocketed, lobbyist-infested, vote-mobilizing power of Big Milk.

The election of Donald Trump changed everything. Trump quickly drew a large bullseye on Canadian dairy, repeatedly flaying the country for “what they've done to our dairy farm workers. A disgrace, it's a disgrace.” Tensions reached a fevered pitch by June 2018, when Trump attacked Justin Trudeau as “meek and mild…dishonest and weak” after the Prime Minister swore to defend Canadian dairy farmers.

Saputo watched it all unfold and shook his head. He knew the Americans weren't looking to dismantle Canada's entire supply-management system. Instead, the sore point was a relatively new pricing rule around ultrafiltered milk, a protein-rich ingredient increasingly used to make cheese and yogurt. American dairy farmers had enjoyed a mini-boom in recent years by exporting the stuff to Canada, since it wasn't covered by Canada's existing quota system, and the Canadian Border Services Agency didn't even consider the protein concentrates to be milk. Then regulators gifted Canadian farmers with a new pricing category (known as Class 7) that shut out the Americans while opening the door for Canadian farmers to sell their own ultrafiltered milk competitively on world markets.

For a company like Saputo that wants to continue to grow, that means we have to think about markets outside of Canada.

— Lino Saputo Jr.

The decision was unfair, thought Saputo, and it risked prolonging the trade conflict with the U.S. So he took aim. Canadian dairy farmers, he told reporters last June, “want their cake, and they want to eat it too. You can’t hold onto your milk-supply-managed system and have a class of milk competing with world markets at the same time.”

Against the backdrop of the flailing U.S. trade talks, Saputo’s message—one he pounded away at in conference calls, speeches and media interviews—made for compelling headlines. For consumers outside of Quebec, it might have been the first time they made the connection between the Saputo on their mozzarella wrapper and an actual person, even though the company’s brands—like Neilsen, Dairyland and Milk2Go milk, as well as Armstrong cheese and Frigo Cheeseheads—fill supermarkets across the country. As for the Canadian dairy industry, the sound you might have heard after Saputo spoke out was the collective thud of cartel members’ jaws hitting the floor. Dairy executives quickly denounced Saputo’s comments as a “product of confusion,” a “wrong attack” and “invalid.” “The association representing dairy processors across Canada continues to support both supply management and Class 7,” the head of the Dairy Farmers of Canada gamely insisted. “Thus, the sector speaks with one voice.”

Except it didn't. And how could it? Saputo Inc. isn't the same company it was when Canada succeeded in excluding supply management from the 1988 Canada-U.S. trade deal and, later, NAFTA. In just the past year and a half, Saputo has spent $3.6 billion on six acquisitions. One of those was in Canada (a small, Ontario-based maker of specialty cheeses and Icelandic-style yogurt), but the others were in Australia, the U.K. and the U.S. It also operates two plants in Argentina, thanks to its 2003 purchase of that country's third-largest dairy processor. According to Dutch agribusiness firm Rabobank, which tracks the world's largest dairy processors, Saputo ranks eighth in the world—and that was before the company's most recent deal in the U.K.

In the end, when the NAFTA-USMCA dust settled, Canadian negotiators agreed to do away with Class 7. Saputo has no regrets about breaking with the dairy lobby on the issue, calling their arguments “propaganda.”

“It was a two-tiered system, and dairy farmers don't like to hear that, so I probably didn't make too many friends at the farm level,” he admits. “But I cannot speak from both sides of my mouth—I can't talk to dairy farmers in Australia, in the United States, in Europe, and tell them what they want to hear when I'm there, and then tell our dairy farmers what they want to hear when I'm here, because they're often two opposing views.”

None of this is to say Saputo opposes Canada’s supply-management system. “I am for the milk-supply-managed system because that’s what the dairy farmers want,” he says. “But for a company like Saputo that wants to continue to grow, that means we have to think about markets outside of Canada.”

That's because the artificially high milk prices paid to Canadian farmers (and then passed on to Canadian consumers) mean products made from that milk will never be competitive for export to the rest of the world. That was a driving force behind the surprise announcement in 1997 that Saputo (sales: $450 million) would swallow U.S. cheesemaker Stella (sales: $800 million).

The deal cemented Saputo’s reputation as one of the most efficient operators in the food industry. Dino Dello Sbarba, the company’s former president and chief operating officer, now retired, recalls touring a Stella plant with Mr. Saputo (which is how he refers to the elder Saputo) and Lino Jr. at the time. “We saw how disorganized it was, and it was obvious to us we could turn Stella around and make a lot of money,” Dello Sbarba says. “We didn’t see the complexity of their systems or their sales, or how they were managing their marketing. We just saw they didn’t know what they were doing from an operating standpoint, and we did.” Almost immediately after taking over, he says Saputo slashed the amount of cheese Stella produced by 15%, yet was able to boost earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization by 50%.

It was a model for the frenzied deal-making to come. Since buying Stella, Saputo has spent in excess of $7 billion on more than 30 acquisitions, from tuck-in businesses that complemented its existing operations to transformational transactions that took the company into new countries and markets.

It’s worth pausing for a moment to reflect on that number: 30. As a rule of thumb, business consultants will tell you that anywhere from 40% to 60% of M&A transactions are considered failures because they don’t deliver the promised results. Companies overpay, cultures clash, egos get in the way. Which makes Saputo Inc.'s Pac-Manlike pace of acquisitions all the more remarkable. Aside from two small European plants the company bought in the mid-2000s and ultimately closed—because they didn’t have the critical mass needed to compete profitably—the company has never botched an acquisition. “They’re very disciplined from a financial perspective, but I’d say even more importantly from an operational perspective, they really take the time to make sure that the cultures are aligned, or they have a clear path to making that happen,” says Mark Petrie, an analyst with CIBC World Markets who has covered the company for the last decade and currently has a “neutral” rating on the stock.

Ask any Saputo executive for the secret to the company’s track record and they’ll tell you it’s the ability to quickly infuse recently acquired businesses with Saputo’s values of accountability, entrepreneurialism and its family business ethic. (The mammoth operation even feels like a small family company at times—last year, one Australian journalist begged the CEO on air to hire a local spokesperson so they didn’t always have to go to him directly for comment.) Before even beginning to make technology or systems changes to new business units, the company sets out to determine which employees “get” the Saputo culture. “It’s non-negotiable who we are, what our culture is and what our expectations are of them,” says Carl Colizza, president and COO of Saputo’s dairy business in Canada and Argentina, who has been with the company for two decades. “Usually within a very short window, we know who understands us and who doesn’t, and we part ways if we have to.”

A couple of days after Colizza joined the company in 1998, Lino Saputo noticed a new face among his 3,000 employees and stopped to chat with him. The pair discovered a shared love of hockey—a passion that has played a key role in helping transfer the Saputo culture to its far-flung plants.

To call Saputo a hockey nut would be an understatement (les Canadiens, bien sûr). In addition to playing in net, he’s also part owner of Quartexx Management, a player agency that represents Patrice Bergeron, Kris Letang and Bryan Little. A few years ago, while playing hockey with one of his sons at a crowded Montreal rink, Saputo struck on the idea of building his own arena. Saputo calls himself a “closet architect,” so he drew up a design, complete with executive boardroom and high performance gym. The three-on-three rink gets rented out for $300 an hour, but it also plays home to an annual company-wide tournament involving hundreds of Saputo employees from across North America. Saputo himself also helped create a draft so teams would have a mix of players from across the company. “People end up going back to their plants, and they become ambassadors of our culture,” says Colizza.

Saputo plays in the tournament as a goalie, and Colizza says that on the ice, he's just another player. No one holds back. In fact, Colizza still likes to recall the year his team defeated Saputo's in the semifinals. “I was fortunate enough to score three goals on him that game, and I wasn't shy about reminding him, either,” says Colizza, who notes the boss's goaltending has improved with age. Says Saputo of his skills between the posts: “I like to think I can hold my own.”

The company has since created baseball, basketball and soccer tournaments. (Two employees came up from Argentina for the latter, one who had never left the town where he lived and worked at the local Saputo plant.)

The rabid Habs fan hosts a company-wide hockey tournament at his private arena every year. As for his skills in net, he says: 'I like to think I can hold my own.'Studio Le Quartier

Whenever Saputo visits any of the company’s plants and sees players from one of the tournaments, he stops to talk. But he just as easily builds rapport with employees he hasn’t faced on the ice. Mitch Garber, the Montreal businessman and chair of Cirque du Soleil, has known Saputo for close to 15 years—their children attended the same school—and he considers Saputo a close friend. He occasionally visits Saputo plants as part of fundraising efforts for Montreal’s United Way Centraide charity. (Saputo’s family has been a major supporter of the charity over the years.)

“I've watched him walk the floors, and Lino will stop with almost every employee, shake their hand, know their name, look them in the eye, know when they joined the company, what their family situation is,” Garber says. “We've never discussed it, but I feel he knows that with the name Saputo, there potentially comes intimidation or nervousness on the part of people, because of the wealth and the brand. There's a cognizance he could have that effect on people, and he disarms it right away.”

The Saputo empire owes a lot to that most exotic of dishes, pizza. In the mid-1950s, the Italian staple was just starting to catch on in Canada (the first pizza ovens weren’t imported until 1957), and early stories about this miraculous new food included instructions on how to pronounce the word.

Giuseppe Saputo and his eldest son, Frank, arrived on Canadian shores from Sicily shortly before pizza did, in 1950. Two years later, the rest of their family, including Emanuele (a.k.a. Lino Sr.), joined them in Montreal. Back in Italy, Giuseppe had been a cheesemaker, but in Canada he took a job as a labourer. Emanuele convinced him to return to the cheese business, and with a $500 investment and a bicycle to make mozzarella deliveries, the business was soon expanding alongside the pizza boom.

Eventually Lino Sr. (now 81) took over the business, which continued to expand. In the early 1970s, however, the Montreal Police Department’s organized crime squad raided the company’s factory, accusing the Saputos of having ties to a New York crime boss. All that resulted from the raid was a $350 fine for violating the health code, but for months newspapers were filled with stories about the incident. “For some reason, being Sicilian and having success wasn’t normal,” Lino Sr. said later. “It was very tough and cheap, what they did to me in 1972.”

Lino Jr. was around five at the time, and says he and his siblings were completely unaware of the raid and its fallout. “God, my mom was a champ,” he says, noting his father was rarely home because of work. “She completely protected my brother and sister and I from that. We only learned about it when we got older and started reading the papers.”

As a child, Saputo Jr. knew he wanted to join his father in the company. At 10, he was sweeping floors and hand-wrapping cheese, and by 13 he began helping with deliveries. Lunches involved scooping ricotta out of vats and putting it on baguettes. To this day, that workhorse staple of Italian kitchens remains Saputo’s favourite cheese—he eats it every day—even though his company’s Le Cendrillon goat cheese by Alexis de Portneuf won best cheese in the world in 2009.

Throughout Saputo’s teens, he learned in detail the process for turning milk into cheese and continued working his way through the company during summers while completing university. He’d originally planned to attend St. Francis Xavier University in Nova Scotia, but he met and fell in love with his future wife, Amelia, and ended up staying in Montreal, where he earned a political science degree from Concordia. The couple married when they were in their mid-20s, and within five years they had two sons, Emanuele (Manny) and Giordano. By his early 30s, Saputo had moved from managing plants to overseeing the company’s rapidly expanding manufacturing operations.

For all Saputo's growth, however, Lino Sr. saw trouble ahead if it remained a family-owned business.

Lino Saputo Jr. isn’t exactly a household name outside Quebec, but the scion oversees a global dairy empire.Studio Le Quartier

Large family businesses are notoriously difficult to manage, particularly when it comes to transferring power from one generation to the next. At the time, the board of directors was filled with Saputos—Lino Sr.'s brothers and sisters all had smaller stakes in the company, and many of their children were on the payroll too. “My father would have these monthly meetings with his family, but the challenge for him was that a lot of the discussion was more emotional than strategic or logical,” says Lino Jr. So, Lino Sr. decided to take the company public in 1997. “My extended family recognized that they would no longer be owners but rather shareholders, and there’s a big difference between the two,” says the son. “Having that corporate governance structure of a public company would allow us to think about things more strategically.” (Unlike many other family-controlled companies in Canada, Saputo doesn’t have a dual-class share structure, which gives founders disproportionate control through multiple-voting shares. A holding company controlled by Lino Sr. owns 33% of Saputo; a separate one controlled by his brother Frank owns 10%.)

The IPO meant a lot of Saputos had to go. “It was clear to all family members, including to myself and my brother, that if we wanted to put in the time and be part of this organization moving forward, we could,” says Saputo. “But we have to deliver on the deliverables just like everybody else.” His older brother, Joey, held various senior management positions but left a decade after the IPO to oversee the Montreal Impact soccer club, which he'd launched in 1992. (He stepped down as president of the club this past January.)

Lino Jr. took up his father’s challenge, but the relationship between father and son was often tense. While Lino Sr. was famous for his hot Sicilian temper, Dello Sbarba says he would unleash his harshest criticism on Lino Jr. in front of other executives and employees. Afterward, Dello Sbarba and others, feeling the father was being unfair, would offer their help, but Lino Jr. refused. “He was always very private,” says Dello Sbarba. “He’d say, ‘Guys, this is my issue. I’ll deal with it.’”

By 2003, Lino Sr. was ready to retire, and the board formed a committee to find a successor. Though Canada has no shortage of entitled scions who’ve been handed the keys to the CEO’s office no matter how unqualified they were for the post, Saputo insists that was never the case with him. Growing up, he says, he’d have settled for a position as supervisor or plant manager, if it came to that. “I’ve been very fortunate to have been guided by some very good people who saw more potential in me than I saw in myself,” he says. In the end, he won the job. “I think they understood that I knew the business and the industry very well, and that culturally there was a strong connection between the way I live and the way the company operates.”

Will another Saputo replace Lino Jr. when he eventually retires? That’s far from certain. Of Saputo’s two sons, one is a musician in Nashville and the other plays professional hockey in France. The latter has expressed an interest in joining the company, and Saputo says he would welcome that, but he would have to prove himself. “There’s no obligation that the next generation of leadership at Saputo has to be a Saputo,” he says. “We’ve got a pool of very talented leaders, and as long as the culture stays alive, it doesn’t have to be a Saputo.”

As for his father, Lino Jr. says their relationship has “inverted,” and now he draws comfort from consulting Lino Sr. when times are difficult, as they are now. “He is the calming influence in my life, where historically my dad was the guy putting most of the pressure on me,” Saputo says. “My dad will say as long as you wake up every morning and ask yourself 'Have you done the best you can do?' and the answer is yes, don't worry about the results, because they're going to come.”

Early in 2018, bushfires raged across Australia’s Victoria state. Caught in the middle of some of the blazes were several dairy farms that supplied Warrnambool Cheese and Butter (WCB). Four years earlier, Saputo had emerged from a bidding war for WCB, beating out Murray Goulburn Co-op, and Lino Saputo Jr. was in Australia for meetings at the WCB plant.

Wanting to help, but not wanting to intrude, Saputo had his staff reach out, and once he got the all-clear, he visited five of the farms. Some were burned to the ground, and other farmers were rallying to help. “There was this great chemistry and camaraderie among the dairy farmers, which I loved to see,” he says. One farmer who'd been hit told Saputo all his fencing had burned so he couldn't contain his cows. Saputo had his people bring new fencing over that afternoon.

The CEO has never talked publicly about the visit, and he’s caught off guard when asked about it now. (Another executive had mentioned it earlier in the day.) “I don’t know how you know that. We weren’t trying to get mileage—it wasn’t a marketing ploy,” he says uneasily. “It was just a question of doing the right thing.”

Saputo could easily have used the visits to his advantage. At the time, the company was in the process of buying Murray Goulburn (MG), the co-op he'd beat out for WCB in 2014. MG had made some terrible decisions that left it deep in debt and losing suppliers. After attending dozens of town halls with the co-op's farmer-shareholders, Saputo clinched the deal last spring. He needed one vote more than 50% to win; he got 98.1%.

Saputo and his father had been stalking Australia for 12 years before making their first deal there. The allure was clear: its proximity to Asia, where dairy consumption is low but growing fast. China, for instance, consumes just 36 kilograms per person of fluid milk, one-third the annual world average and just one-10th the level consumed by people in developed countries.

Australia is perfectly positioned to serve that market, not just because of its geography but because of its trade agreements with Asian markets. Still, the industry is struggling at home because of low domestic prices and an oversupply of milk, with a growing number of farmers getting out of the business. That's just one of the challenges facing Saputo. “Without strong milk production, we don't have an industry. All we have is brick-and-mortar and stainless steel plants,” he says. “So we've got to take care of our farmers. It doesn't mean we can say yes to all of their requests, but we'll take the time to explain why it's yes or why it's no.”

Here at home, Saputo the company faces its own set of challenges. While Canada agreed to scrap Class 7, the pricing system for ultrafiltered milk Saputo came out against, negotiators also dealt away greater access to the Canadian dairy market under the new trade agreement than Saputo expected. All told, he says, between the replacement trade deal with the United States and Mexico (USMCA), the trade deal with Europe (CETA), and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), roughly 12% of Canada's dairy market is now open to foreign imports.

It’s unclear how Saputo and the rest of Canada’s dairy industry will be affected by these changes. But with its ever expanding international reach, the company may be well positioned. In a research note after its purchase of the U.K.'s Dairy Crest, CIBC’s Petrie noted it could position the Canadian-based company to ship dairy products to Canada from its international operations. “We expect Saputo to leverage this new production, likely focused on accelerating [Dairy Crest’s] limited export business, including to Canada.”

Still, tastes are changing in North America as consumers turn away from conventional milk. Even the recently updated Canada Food Guide downplays milk and cheese consumption—staples since the guide's advent in the 1940s. Per-capita fluid milk consumption has shrunk by nearly one-quarter since the end of the 1990s, and the pace of the decline is accelerating. From 2016 to 2017, consumption fell by 4%.

Saputo’s answer is to go premium. So-called “value-added” milk products are growing fast—things like the single-serve flavoured milks offered by Saputo’s Milk2Go label. Another area where Saputo sees growth is in high-protein, low-lactose milk, such as its Joyya brand, an ultrafiltered milk that it launched last fall. However, the company is going up against Coca-Cola’s Fairlife brand, also a high-protein, low-lactose milk that’s available across the country. Coke is in the process of building an $85-million plant in Peterborough, Ontario. In the meantime, the beverage giant received a temporary licence from Ottawa to import all of its milk from the U.S.

Then there’s that small but growing slice of the population that’s cut out dairy altogether. In Saputo’s most recent conference call, he specifically mentioned plant-based protein drinks, like soy, almond and coconut milk, as a competitive threat. Asked if the company plans on moving into that sector, Saputo says it’s definitely something he’s looking at. “We can’t deny plant-based beverages are a threat to the fluid milk category,” he says. “We’re not going to create our own brand. However, if there is an opportunity for us to make an acquisition of a company that already has a great following, that’s something we would consider.”

Saputo certainly has the room to make more deals. For months before buying Dairy Crest, Saputo had been saying the company had roughly $3 billion it could spend on acquisitions without having to tap equity markets, and that it had five or so potential takeovers in the pipeline. That means it still has more than $1 billion to spend, so expect the deals to keep coming.

“From an evolutionary perspective, you need to be moving forward. Otherwise you're moving back,” says Saputo. “So, the potential for us to go beyond the $13 billion in revenue we're at is very good. Could we be at $15 billion? Could we be $17 billion? Could we be $20 billion? I think the answer is yes, because the opportunities we're seeing for potential acquisitions is very real.”

The only question, then, is how big this big cheese could get.

Laying on the fromage: tasting notes on some of Saputo’s artisanal cheeses

La Sauvagine

Smooth and rustic: La Sauvagine is a cow milk cheese with a moist and supple rind that ripens from the outside in; runny ivory body; fresh butter taste with a hint of mushrooms; melts in the mouth and is flavourful; culminating with a rustic taste.

Le Cendrillon

Rich and robust: Crowned Best Cheese in the World at the 2009 World Cheese Awards. Vegetable-ash-covered cheese with a marble-textured rind and a smooth ivory body; acidulous, semi-strong taste that becomes more pronounced with age.

Cantonnier

Supple and nutty: Cantonnier is a semi-soft pressed cheese, uncooked and surface ripened with a washed rind. It distinguishes itself with its effervescent flavour, reminiscent of fruity cream and fresh apples.

Bleubry

Rich and pronounced: A smooth version of the blue cheeses; frank and delicate; creamy, not too salty; a product of the marriage between brie and blue cheeses.

La tentation de Laurier

Buttery and delicate: When young, this cheese has a creamy texture like that of whipped cream, with a fresh cream flavour and a slighty acidic aftertaste. The whipped texture becomes smooth and spreadable when it reaches its peak, thus bringing out the pronounced butter flavour. It melts in your mouth.