Fisherman Brendon Coulstring throws an undersized lobster back into the ocean off Yarmouth, N.S. The province's fishermen have been busy feeding Asian markets where Chinese tariffs on American lobster have increased demand for Canadian crustaceans.Photography by Dean Casavechia/The Globe and Mail

Dumping day is what locals call the first day of lobster fishing season in Nova Scotia. Today is Dec. 13, 2018, just over two weeks after dumping day. There’s no special name for today. But if you’re Bill Olsen, all the days these days are special. Olsen is 56 years old and has been a lobster fisherman for 40 of those years. He fishes for lobster out of Chegoggin Point, near Yarmouth. Over the years, lobster’s popularity has waxed and waned. These days, though, lobster is all the rage. Especially Canadian lobster.

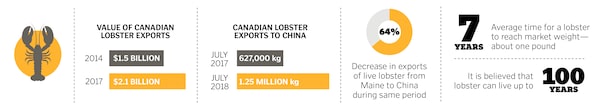

Olsen can thank Donald Trump. Last summer, in retaliation for sweeping new duties the United States imposed on Chinese imports, China slapped a 25-per-cent tariff on a long list of American goods, including live lobster. In 2017, China bought about $128 million (U.S.) worth of lobster from the U.S., and in July, when the tariff took effect, Chinese consumers promptly shifted their crustacean allegiance northward. Canadian shipments of lobster to China – 98 per cent of which come from Nova Scotia – nearly doubled compared to the year before, from $12-million to $21-million. Demand was so great that Halifax’s Stanfield International Airport couldn’t keep up with the freight shipments; chartered jets had to be flown out of Moncton and Montreal. Lobster was sent via passenger aircraft.

Such demand means Olsen works 14 hours a day, seven days a week. Today, he’s out on his boat, the Isabell Anne, just after four in the morning. It’s dark and cold, about -12 degrees with the windchill, and it feels even colder when you’re peeing off the back of the boat. The water’s rough, the vessel sheathed in ice. Olsen’s lobster traps, called pots, lie on the bottom of the ocean, about an hour from shore. Eighteen to 20 pots are attached to a rope, with a buoy at each end. Olsen and his three-man crew pull up each line with a hook and attach it to a hauler, a large mechanical wheel that pulls the pots up to the side of the boat. Each pot is emptied and the caught lobster sorted. Smaller ones or those carrying eggs are thrown back in the water. Keepers have their claws quickly secured by rubber bands. When a pot is empty, a fresh bait bag, containing frozen herring and redfish, is placed on a bait stick and inserted into the pot. The pot moves to the back of the boat and, once the whole line is checked, it’s dumped back in the ocean.

Olsen and his crew pull his pots in about 18 times over the course of the day, checking 375 pots all told and catching 815 pounds of lobster. When they get back to the dock, it's dark again, and a buyer, Woods Harbour Lobster, is there to greet them. Woods Harbour weighs and buys the catch, and it's immediately transferred to their temperature-controlled facility not far from the dock. There, each lobster is put on a conveyor belt and sorted by weight and health. Some are shipped right away, others put in a holding tank for storage. (A lobster can be stored for five months in frigid water, which induces a sort of stasis.) The goal is to get the lobster to customers in Asia within 40 hours. Cargo planes go out the next day; one plane carries 150,000 pounds of lobster.

Olsen’s 815-pound catch is about 1,000 pounds less than it was the year before. The water’s been colder than normal, about four degrees, and lobster go into hibernation when it gets that chilly. But Christmas is on its way, then Chinese New Year, so demand for Olsen’s lobster is just going to get higher, especially with those tariffs stalling U.S. imports. The Isabell Anne will be out again first thing next morning.

It's early in the morning off the southern coast of Nova Scotia. Aboard the Isabell Ann, fisherman Bill Olsen looks for the buoy that marks where his lobster pots are.

Ryan Olsen pulls one of the lobster pots aboard the boat.

Brendon Coulstring makes sure the lobsters are the right size before banding them and placing them into a holding crate.

At Woods Harbour Lobster, just outside Yarmouth, lobsters are sorted by weight on a machine.

Trays of lobster are then loaded up to be stacked and placed in long-term storage. Depending on the time of year, the lobster will sit there for three to five months.

Jason Nickerson stands on top of 80,000 pounds of lobster in the long-term storage tank. When full, the tank will hold 160,000 pounds of lobster.

Workers at Gateway Facilities ULC move unit load devices, or ULDs, filled with Nova Scotia lobster. These lobster are bound for Asian markets, where demand for the Canadian crustaceans has been high since a trade feud with the United States put heavy tariffs on live lobster from the United States.

A large shipment of lobster waits to be loaded onto a Korean Airlines flight at Halifax Stanfield International Airport.