Sam Island/The Globe and Mail

You might have heard there's a federal election coming soon. Of course, the recent budget made that plain enough, with goodies and special programs for nearly every identifiable demographic: seniors, young homebuyers, small business owners, rural folk, middle-aged job hunters, Indigenous people, and on and on. If there's a recognizable segment of society out there, you can bet there's a pre-election perk with their name on it—with a single unfortunate exception.

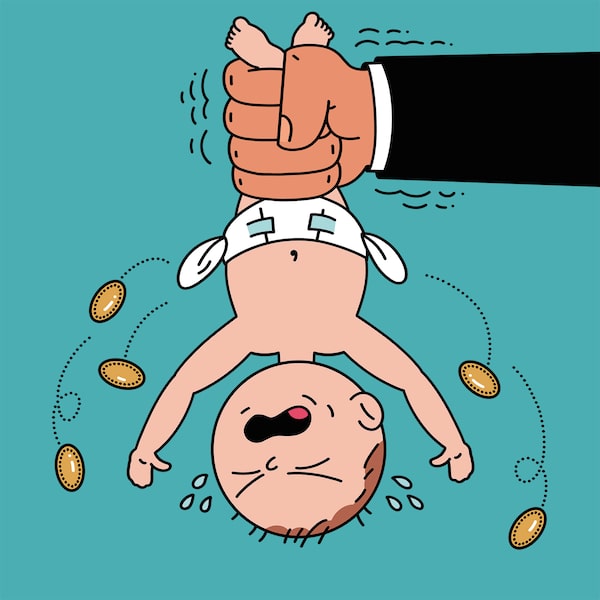

The one slice of Canadian demography certain to be ignored in the coming election is, tragically, the very group with the greatest stake in its outcome: newborns. They may not be able to feed themselves, or even speak or roll over right now—and they certainly can’t vote—but these adorable little droolers will one day be handed a bill for every one of our collective mistakes and indulgences. Given the size and shape of this future burden, we ought to consider their absence from electoral debate to be a national, intergenerational embarrassment.

Recently, the C.D. Howe Institute used an economic technique called lifetime generational accounting to assess the fairness of Canada's fiscal policies. While the math is complicated, generational accounting is easier to understand if you imagine a Vegas-style gamble based on your birth year. Every generation pays taxes and gets governmentprovided benefits in return. The cost of broadly shared programs, such as defence or the bureaucracy, is generally split equally across all generations. But the size and scope of individually focused benefits—health care, education, welfare and public pensions, along with the taxes meant to pay for them—can vary greatly over time, depending on politics and demographics. Winning this game means receiving a lavish supply of benefits while being subject to a relatively small net tax burden. Losing means getting stuck paying for a huge party people born in other years attended.

Let’s start with Canada’s most dominant generation. Baby boomers, according to C.D. Howe Institute figures, can expect to pay, on a net basis, around $200,000 per person over their lifetimes for all the health care, education and other social services they receive. (All figures adjusted to birth-year values.) That might seem like a lot, but it’s nothing compared to the current generation of newborns: Over their lives, they’ll each pay an estimated $736,000 more in taxes than they will receive in individual benefits. The luckiest Canadians are those born in the 1970s. On average, these kids of boomer parents face a net tax burden of just $27,000 each for their lifetime of social benefits. “Generally speaking, boomers and their children fare well in this scenario,” says Parisa Mahboubi, a C.D. Howe senior policy analyst. “But their grandkids do not.” Now you know why babies cry.

This huge discrepancy between newborns and older generations is the result of an aging population, which reduces the proportion of working folk who are available to pay taxes, while increasing the amount of health care and elderly benefits owing, combined with the accumulation of past government debt. Mahboubi’s results also reveal some striking gender disparities. A male newborn can expect to pay $1.5 million in net taxes over his lifetime, whereas a female newborn will contribute a mere $82,000. The reason? Women work and earn less, meaning they pay fewer taxes. Plus, they tend to live longer, and are more likely to receive child benefit and social assistance payments.

Why RBC is becoming the New England Patriots of Bay Street

How Shopify made Kylie Jenner rich(er)

Opinion: The Liberals’ CMHC mortgage madness is another subprime crisis waiting to happen

Generational accounting was first applied to Canada in the mid-1990s, during an era of uncontrolled government spending and rapidly rising public debt. Economists Philip Oreopoulos, then an analyst at the Montreal-based Institute for Research on Public Policy and now a University of Toronto professor, and Boston University’s Laurence Kotlikoff used similar calculations to demonstrate that “current fiscal policy is unsustainable and is placing a higher net tax burden on future generations” of Canadians. Their projections suggested future tax rates would have to double to bring fiscal policy back into balance. This outcome was avoided by former finance minister Paul Martin’s famously austere 1995 federal budget, which dramatically altered the path of federal finances. That said, our commitment to intertemporal fairness appears to be slipping somewhat, as evidenced by the current Liberal government’s ongoing affection for large deficits.

Looking even further into the future, generational accounting also allows for us to calculate the tax burden on those Canadians not yet born—a crucial test of intergenerational fairness. According to Mahboubi, unborn generations of Canadians face lifetime net taxes of $633,000, somewhat less than our current newborn’s tax bill of $736,000. This, she suggests, is reason for optimism. And yet her optimism is heavily reliant on two key assumptions about future government policy. In particular, these results require keeping a tight lid on health care spending and maintaining our current high levels of immigration. Immigration is crucial to restocking the workforce, while health care spending restraint is necessary for limiting potentially explosive costs associated with an aging population. Both are hot-button issues that generate plenty of political debate. If either succumbs to public pressure in October, the outlook for upcoming generations will suddenly get much grimmer.

There is, however, one more policy adult Canadians can choose in order to lessen the burden on our youngest and most fiscally vulnerable citizens: raise the retirement age.

Increasing the retirement age from 65 to at least 67 would loosen Canada's demographic squeeze by extracting more taxes from current workers and slowing the rise of new retirees. Recall that in 2012 former prime minister Stephen Harper planned to push the age of eligibility for Old Age Security to 67 (as most other developed countries are now doing), only to have Justin Trudeau undo it in an effort to pander to senior voters. And when you consider that Canadians are living, on average, nearly a decade longer than they did in the 1960s, when 65 was arbitrarily chosen as the standard retirement age, working a few extra years doesn't seem like a very big request.

“Canadians who have paid the lowest taxes could be asked to stay in the workforce longer to reduce the burden on future generations,” says Mahboubi. Such a plan also seems entirely fair, since those being asked to work a little bit longer are the same folks who’ve massively benefited from the current inequities of the system. And really, is anyone so heartless that they’d force a baby to pay for their golden years?