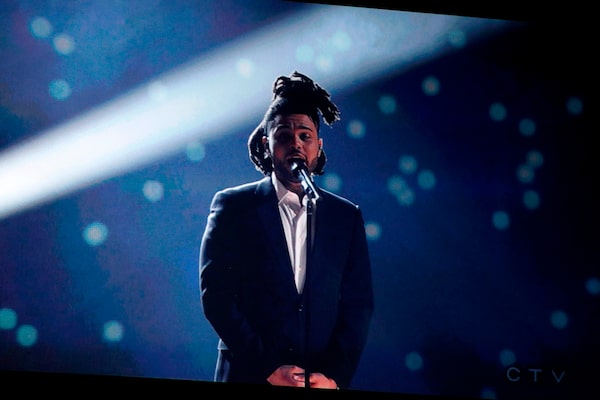

Canadian singer The Weeknd performs via video screen during the Juno Music Awards at Budweiser Gardens in London, Ont., on March 17, 2019.LARS HAGBERG/AFP/Getty Images

There has always been a fuzzy boundary between homage and musical plagiarism, but ever since the copyright-infringement case involving Robin Thicke and the estate of Marvin Gaye in 2015, the line has become more blurred than ever.

When Thicke and co-writer Pharrell Williams were ordered to fork over more than $5-million because of the vague likeness of their hit song Blurred Lines to the clanking dance-party invitation of Gaye’s Got to Give It Up from 1977, music insiders foresaw it as a watershed moment in chord-progression case law. Allegations of plagiarism would be thrown around willy-nilly, that was the fear. As it turned out, those concerns were accurate; the precedent had indeed been set. And in the courtroom you can’t, as they say, unring the bell – not even a disco-era cowbell.

This week it was reported that the Weeknd is being sued by three British songwriters who allege that the Canadian R&B artist copied their work to produce A Lonely Night, a moody song about the gestational outcome of a one-night stand off his hit Grammy-winning 2016 album Starboy.

According to the plaintiffs (Scott McCulloch, Brian Clover and Billy Smith), the pinched composition is I Need to Love, a 15-year-old song they first recorded as members of the band Sonic Religion and subsequently shopped around. The case has not yet gone to trial in Los Angeles, but the aggrieved trio has entered a side-by-side sound clip online as Exhibit A in the court of public opinion.

That cherry-picked passage of I Need to Love is indeed similar to the chorus of A Lonely Night. And perhaps there is a case for compensation. The bigger issue has to do with the increasing prevalence of these types of accusations, and how the charges have set a chill within the songwriting world.

“That little melody in the clip is such a Motown melody, I bet you could find 30 songs with a close variant,” the Juno-winning artist Donovan Woods told me this week. I asked Woods, whose songs have been recorded by the likes of country superstars Tim McGraw and Lady Antebellum’s Charles Kelley, how the litigious culture has affected the music business.

“There’s a big fear for pro songwriters of even just listening to a song someone sends you, because the melody goes in your head and maybe it comes out later when you’re writing over a similar chord progression. And then the other writer can say, ‘I e-mailed them that song on this date,’ and there’s a case to be made.”

Cases are indeed being made. British pop star Ed Sheeran, for example, is sued so often he must impulsively stand up whenever he hears “Will the defendant please rise” on Law and Order reruns.

Another high-profile case recently involved Led Zeppelin’s Robert Plant and Jimmy Page and their classic song Stairway to Heaven. Lawyers representing the late Spirit guitarist Randy California contended that Page had appropriated part of Spirit’s 1967 track Taurus as the basis for the descending chord sequence that opens the iconic Zeppelin song. Page and Plant were initially cleared of plagiarism charges, but the case is under appeal.

As many cases there are that we hear about, much more are settled quietly. To head off expensive trials and bad publicity, backroom deals are made. Much of the trepidation can be traced back to the litigious Gaye estate, which was able to prove copyright infringement even though Thicke’s Blurred Lines had only a stylistic resemblance to Gaye’s infectious groove.

“The song Blurred Lines is a deliberate homage to the original, without actually copying it,” industry veteran Alan Cross told me this week. Cross, who recently wrote about the subject of plagiarism on his popular blog A Journal of Musical Things, takes exception to the verdict of the Blurred Lines case specifically, and with the lawsuit-happy culture that now hangs over the music business in general.

“It’s nonsense,” he explained. “There are only so many chords and so many notes and so many melodies you can put together in a pleasing sort of way. After 65 years of rock ’n’ roll, there’s bound to be duplication.”

Which is true enough. I once suggested to Randy Bachman that the opening cut from his 2015 album Heavy Blues sounded similar to The Who’s Won’t Get Fooled Again. “Well, it’s also the same chords I used on You Ain’t Seen Nothing Yet,” he told me. “We’re all just honouring each other. Chords are chords."

Tell that to the judge.

Brad Wheeler

Brad Wheeler