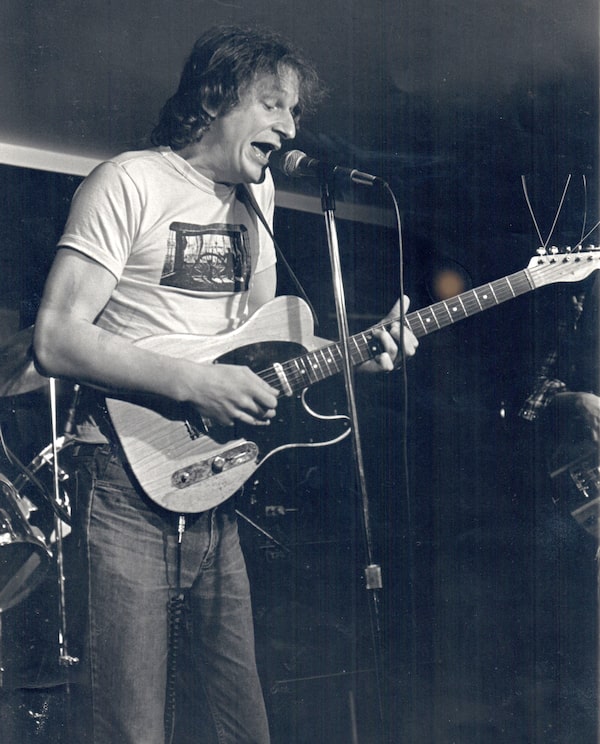

Joe Hall performing.Cordova Bay Archives/Cordova Bay Archives

Joe Hall possessed one of the most fertile imaginations in Canadian songwriting. His concerts in the 1970s and 80s are the stuff of legend: frenetic displays of eclectic music and absurdist theatre in which he seemed to have narrowly escaped a straitjacket. Although his star dimmed in subsequent decades, the prolific artist never stopped writing songs, recording and performing. When news spread recently that he had died, fans across Canada mourned the loss of a gifted, lovable oddball whose commercial success never matched his unbridled talent.

During Mr. Hall’s heyday touring widely with his band the Continental Drift, he often drew comparisons to Frank Zappa for wild performances of songs such as the 1950s greaser epic Johnny Nada, the trailer-park horror Vampire Beavers and the spaghetti-western spoof Nos Hablos Telephonos, which played like zany B-movies themselves, full of eccentric characters and twisted plots. But Mr. Hall also had a poet’s sensitivity, capable of crafting a touching confessional such as Preparing to Begin. “Zappa backed himself into a corner where he couldn’t do a romantic ballad, even if he wanted to,” says guitarist Tony Quarrington, Mr. Hall’s long-time collaborator. “We always tried to do both,” he adds wryly. “That’s what kept us out of the big time – we were too schizophrenic.”

Although he never enjoyed a hit song, Mr. Hall kept writing at a feverish pace. During his career, which began in 1972, he released more than a dozen studio albums and several live recordings. Some, such as 1979’s On the Avenue and the following year’s Rancho Banana, are coveted by those who still own precious vinyl copies. Mr. Hall registered more than 250 compositions with SOCAN, the Canadian songwriters association. But he wrote and performed many more, often brilliant numbers that never appeared on recordings. “Joe’s devotion to his craft was inspiring,” Drift drummer Martin Worthy says, “and his approach to music was completely unique, with unusual chord progressions and lyrical ideas that he somehow made work.”

After Mr. Hall’s death on March 22, his fans posted reminiscences on social media, recalling his albums and performances at bars such as Victoria’s Harpo’s, Calgary’s Refinery, Saskatoon’s Parktown, Toronto’s Edge, Kingston’s Prince George, Montreal’s Rainbow and the Floating Admiral in St. John’s. Craig Macinnis, a former Toronto Star arts reporter, posted a 1,200-word tribute on Facebook that recalled a gig at Ottawa’s Squires Tavern. Mr. Hall was onstage, he wrote, “lying on his back, gurgling and writhing in the throes of some faux epileptic fit … beer foaming from his mouth, his legs and arms twitching spastically in his pretend death throes.” But, Mr. Macinnis added, “I would soon learn that after a berserk set-piece like the aforementioned, Hall could right himself, wipe the beer suds off his chin, and launch straight into a heartfelt ballad sung in a bruised, halting tenor that recalled no other singer in the world.”

Mr. Hall was born Hans Joachim Boenke in Wuppertal, Germany, on My 15, 1947 to Johann Boenke and the former Johanna Maria Zeirmann, who immigrated to Canada three years later and settled in London, Ont. When his parents divorced and his mother remarried, Mr. Hall took his stepfather’s name, to avoid schoolyard taunts (his 1975 album bears his birth name, H.J. Boenke). Mr. Hall learned to play guitar, performed in London coffeehouses and wrote his first song at 17, a bluegrass number called Bluewater Highway. But his interests grew from his mother’s records. “She had a collection of German cowboy music and a lot of calypso records,” he once recalled. “I find the beat very pervasive and also there’s a political aspect I find appealing.”

Mr. Hall moved into Toronto’s bohemian Queen Street West district and in 1971 met Mr. Quarrington, who shared his taste for lyrical and musical puns. Together with keyboardist George Dobo, they became the house band at the Black Bull Tavern, later adding Mr. Worthy on drums and Mr. Quarrington’s brother (and future Governor-General’s Award winning novelist) Paul on bass and moving on to clubs such as the Horseshoe, Colonial, Cameo and El Mocambo. Sporting giant bow ties, sunglasses and sometimes a mophead wig, they fit perfectly into Toronto’s culture of eccentric musical outliers such as Mendelson Joe, David Wilcox, Leon Redbone and Max Mouse and the Gorillas. “Everything about Joe Hall reeks of anti-star,” The Globe and Mail’s Alan Niester wrote in 1978. And yet, his surreal cabaret-style repertoire inspired others, including future Frantics and Puppets Who Kill comic Dan Redican, who recently paid homage to Mr. Hall, calling him “funny, smart, twisted – one of my heroes.”

As for Mr. Hall, a voracious reader, he found inspiration in the most unlikely subjects: the Three Mile Island nuclear accident, a beleaguered barroom stripper, a gun-toting stalker or Hitler pining for his girlfriend in a Caribbean hideaway. “My own favourite themes are apocalypse and boredom," he once told The Globe. "I adopt the persona of the different people involved. I believe in altering my state of mind whenever I can.”

According to Michael Burke, who managed the act for five years, Mr. Hall’s ability to see things from so many angles was his genius and his curse. “He had all these characters in his head,” Mr. Burke said, “but at times he didn’t know which perspective was his.” Mr. Worthy believes Mr. Hall felt trapped wearing what he calls his “loony mask” and wanted to be taken more seriously. Substance abuse became an issue for Mr. Hall, who feared quitting alcohol would hurt his muse. Falling on hard times, he once took a job as night manager of Toronto’s seedy St. Leonard Hotel. Adds Mr. Worthy, “Like all great artists, Joe was a delightfully defective human.”

In 1985, Mr. Hall moved with his second wife, Anna Croutch, to Peterborough, where he collaborated with local acts such as the Silver Hearts, recording at his home studio, Wingnut, and settling into what he called “geezerhood” (also the name of his 2005 album, which contains Dollarton Blues, a poignant song about author Malcolm Lowry’s battle with alcoholism). In Peterborough, Mr. Hall was able to slow down, get sober, enjoy his children and grandchildren and even play a little recreational baseball and table hockey. But he kept returning to Toronto for regular appearances at the Tranzac Club and recorded one final album, released in December, with his old cohorts Mr. Dobo, bassist J.P. Hovercraft and the Juno Award-winning Tony Quarrington.

“’We all just need to love each other and be patient with each other’ are the last words my father ever said to me," Mr. Hall’s eldest daughter, Chandra Corriveau, wrote on Facebook. "Sage advice. Love you Dad.”

Mr. Hall, who died of liver cancer, leaves five children and several grandchildren from two marriages and an earlier relationship. He was 71. A public celebration of Mr. Hall’s life is planned for May 17 in Toronto at the Tranzac Club.