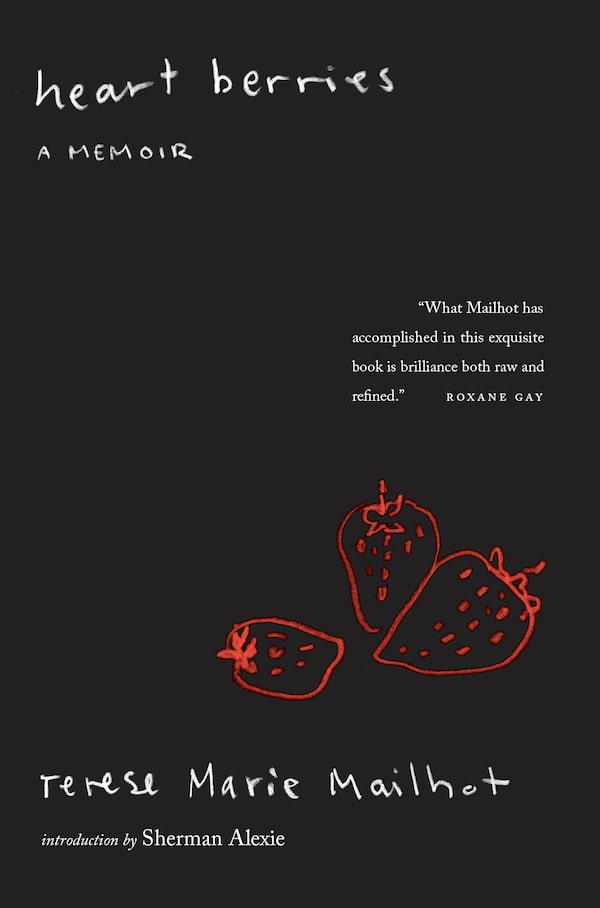

Terese Marie Mailhot's debut book, Heart Berries: A Memoir, has earned rave reviews.Mark Woodward

For somebody denied it their entire life, domestic drudgery can feel, in fact, like a dream.

A short drive from the leafy American university where Terese Marie Mailhot is a post-doc fellow, past a Walmart and an Applebee’s, sits her cookie-cutter subdivision house, where her 12-year-old son is on his Nintendo Switch, while his three-year-old brother is colouring a picture for Mom and Dad. Dad – the author Casey Gray – is brewing coffee (Tim Hortons; they sell it down the road) and whipping up a quesadilla for their little boy.

“I never foresaw any of that for myself, like normalcy,” Maillhot says. “It’s really staggering. It’s very interesting to me. Because I had never seen it.”

Growing up in British Columbia in a house infested with ladybugs, abuse and neglect, Mailhot longed for a kind of ordinary life she didn’t really know existed, certainly not first-hand. Her experience was broken families, abusive parents and hunger. At times, the kids were left alone for days while their mother was at work and their father gone – off on a bender, or chased from the home, finally, for his violence.

The life she leads now is bliss – even without that other thing dominating their lives right now: Mailhot’s recently published debut book Heart Berries: A Memoir has earned rave reviews, made it to the New York Times bestsellers list, landed Mailhot a guest spot on The Daily Show and is a strong contender for the best Canadian book – best book, period – you will read this year. It’s a slim volume you can read in one sitting that wallops with its devastating story and its tremendous prose.

“It’s too ugly – to speak this story,” she writes in the first chapter, Indian Condition. “It sounds like a beggar. How could misfortune follow me so well, and why did I choose it every time?”

Mailhot, 34, is Indigenous from the Seabird Island Band – that’s where she grew up, near Chilliwack, B.C. Her mother was Nlaka’pamux and Mailhot’s maternal grandmother went to residential school, where she learned to clean and pray; she became a devout Christian, but spoke little of her experiences there.

Mailhot’s father, Ken Mailhot, (who also went by Ken Paquette) was also Indigenous. He was a talented artist, but an abusive alcoholic; he met Mailhot’s mother, Karen Joyce Bobb (or Wahzinak) when he was in prison. Mailhot later learned from family and news clippings that he was serving time for abduction of a young girl. He died after being beaten in a Hope, B.C. motel room “over a prostitute or a cigarette,” she writes. “I prefer to tell people it was over a cigarette.”

Bobb was a social justice advocate who worked with prisoners. She was also a poet and a writer. But she too struggled with alcohol and her burden; she regularly heaved abuse at her children. (Bobb stopped drinking before Mailhot was born.)

Mailhot spent her teens in several foster care situations – there was abuse there too. She left school at 13 and moved in with the man who would become her first husband when she was 17 or 18. She was 19 when they married, 20 when their son, Isadore, was born.

One of the devastating events of Mailhot’s life recounted in the book concerns the time when she had just given birth to their second son, Isaiah, the one spending his Saturday morning on the Switch. As Isaiah was born, she lost custody of her then two-year-old son Isadore to Vito, their dad, who lived in the United States, while she was still in Canada. She took her newborn and moved to the U.S. as well, with a plan.

Mailhot's sons, Isaiah and Isadore.courtesy Terese Mailhot

“I had in mind that I was going to work my way up into being someone who could regain custody,” Mailhot explains during an interview at her immaculate home in West Lafayette, Ind. “So I thought ‘Oh, if I could be a receptionist or a high school teacher, then I could afford to litigate.’ I just needed $3,000 to retain a lawyer and to process paperwork. But the problem was that I never became that thing until I was in my late 20s and early 30s where I could afford to even do that, and by then too much time had transpired. It would have been really unfair to Isadore to fight for something he probably at that point didn’t want and I was afraid to even ask because it felt selfish.”

These days, they visit often. The money from her book – there will be more when the residuals start coming in this fall – helps. Isadore, now 14, is doing well. She tells me about a text he sent her before they met up at a fancy hotel over the holidays.

“’I just want you to know that when I’m smiling, I’m smiling for you and I’m here and enjoying my life and I think about you in these really good ways, mom. And that everything is going to be okay,’” she recounts. “He really wanted to tell me that I didn’t need to feel bad anymore that I wasn’t there for him in the way that I’m there for Isaiah. That gave me a lot of peace to see that, that he’s very content in his life with his father.”

Mailhot’s talent, evident on every page of Heart Berries, goes back to her childhood. She grew up reading her mother’s work and also in a house full of books; Bobb had an extensive library in the house and they often visited bookstores.

She began writing when she was very young – Grade 1, she figures. “It was something I knew how to do. I knew how to compose a good sentence from a young age.”

Mailhot, who grew up surrounded by books. started writing at a young age.Courtesy Terese Mailhot

When Mailhot dropped out of school at 13, she continued to read and write. She read indiscriminately – Steinbeck, Emily Dickinson, romance novels. (She later completed her GED as an adult.)

In her 30s, she has been able to turn the ugly things she had experienced into a gorgeous work of art.

Heart Berries is written through the lens of a breakdown; the terrible events of Mailhot’s life led her to commit herself a few days before Christmas, 2013. She was heartbroken at the time – she and Gray, her boyfriend at the time, had had a tumultuous relationship and they had split up. The loss of Isadore and other shattering events in her life contributed to the breakdown. She was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder, an eating disorder and bipolar II disorder.

When she arrived at the mental-health facility, she was given a notebook. She started writing to Gray: a raw plea, a harrowing explanation, a blood-on-the-page confession of the kind of intense love that slays you. “I’d like this letter to be ashamed and wild like me,” she writes in Indian Sick, the chapter she first began writing in the institution.

“I felt angry that I was going through this over a man in the midst of trying to become a graduate student at places that were going to be a dream for me if I got into either,” she explains in the interview – New Mexico State University and Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA); she got into both. She later fictionalized what she had written. And then, she went back and wrote it as memoir.

“I [wanted] to illustrate how painful it is to love someone when you really never knew what normal looked like; like, you’d never seen a mother bond with a child before, you’ve never seen a successful marriage. You’ve only seen broken marriages that devastated an entire family for the rest of their life. So for me, I was broken by simply loving anybody that much, because I knew it was going to ruin me.”

Gray had been Mailhot’s undergrad professor at New Mexico State University. She confessed her feelings for him after their class – creative writing fiction – had ended, during the postcourse teacher-student conference to discuss her mark. “It was undoubtedly an A,” Gray calls out, from the kitchen. “She was the best student I ever had, by far.”

He later sits down with us at the table with its floral tablecloth, and pink and yellow flowers from Bloomsbury – a congratulatory bouquet following the news that it will publish her book in Britain. On the wall behind the table is a print of Ken Mailhot’s Man Emerging – a traditional Salish depiction of a man riding a whale. Gray had tracked it down and bought it as a gift for Mailhot – before Gray knew what happened between father and daughter.

I ask him what it was like to read the book.

“It did kind of open up and help me understand her more and the depth of what she’s gone through and frankly the hurt I caused her,” he says. “It was really beautiful and really hard to read, frankly. And I knew it was powerful and I knew it was amazing.”

Could this thoughtful, affable guy in the t-shirt, serving cookies and pouring coffee and coaxing the three-year-old onto the potty, be the Casey from the book, the lothario who rips Mailhot’s heart out? He points out that there are different perspectives; if he had written the book, it would have perhaps been somewhat different – but no more or less true.

“The book’s about Terese and it’s all filtered through her eyes and it’s about the way she saw me and our relationship and the way she saw me when she was deeply hurt by me and deeply hurt by the world and deeply hurt in general and going through something difficult,” he says. “And I don’t begrudge her that vision or that artistic expression at all. I’m proud of her; it’s a fantastic book.”

I think defying the odds, it makes me want to tell people they can do it too.

— Terese Marie Mailhot

Mailhot tells me a story she has heard from another interviewer, about a bookseller who expressed his disappointment that she ended up marrying Gray. I ask Gray what that’s like, for people to judge him like that and whether he had any misgivings about the book’s contents.

“This is Terese’s very true view of things. I just wouldn’t dream of asking her to change a word of it.”

These days their fights are not about love and fidelity, but the dishes and laundry. “Our marriage is nice and boring now,” she says.

They got married at the courthouse; Mailhot, nauseous and pregnant with Casey, wore leggings. Isaiah was their witness. The marriage helped with health insurance.

“I was going to ride his coattails,” she says. “I was just going to write while he had a good tenure-track job; that was my vision. So things have changed, dramatically.”

There is a key, sickening revelation in the book, something Mailhot remembers about her father, inexplicably while sitting in a Starbucks. She had a panic attack – couldn’t breathe, couldn’t walk. She felt numb for days. She was highly medicated after that. She had nearly a year of panic attacks and breakdowns and tears. Gray looked after her.

“I think it was because I was really safe in my life,” she says, when I ask why she thinks the memory surfaced at that time. “I felt really good about myself. I was working on a graduate thesis, I was writing all of these stories about a native woman with a lot of bravado who was making poor decisions, but she was very explicit and very empowered, even though doing all that bad. And I was a college instructor, which made my whole family proud, and I had a good relationship with Casey. Things were just working. Things were really good. I think that’s why.”

Mailhot and I were initially supposed to meet in Vancouver a month earlier; she was coming home for a book launch and an honouring ceremony at the community school at Seabird Island – an event she had told an interviewer ahead of time was the thing she was most looking forward to on her book tour.

She had prepared for the tour – for talking in interview after interview about the trauma she experienced – by attending a group partial hospitalization program, which she wrote about for Guernica magazine.

Mailhot and her brother Ovila, with Buddy and Rocco.courtesy Terese Mailhot

She cancelled on short notice. Things were not going well at home in the two weeks she had been out touring her book in the United States – little Casey was regressing in his toilet training and Isaiah explicitly asked his mother not to leave again.

Now, she is doing better.

“I feel really strong. The thing about PTSD is I get irritable, I get triggered by things, but I feel like in my life this is the strongest I’ve ever been, which is really odd to experience. And I’m really good about knowing my limits. Like cancelling the tour; I knew if I left my kids, I would experience too much grief and guilt. I would feel ashamed that I didn’t do the mom thing before the career thing.”

There was other stuff going on at the time too – although this is not the reason she cancelled the tour. Just as the book was being released, allegations of sexual impropriety surfaced about the celebrated Indigenous American writer Sherman Alexie. Alexie was a teacher and mentor of Mailhot’s. “It broke my heart. It felt like losing someone that I wanted to be my dad. And I don’t trust a lot of men. But it also makes me suspicious of everything now, which I wasn’t prepared for,” Mailhot says.

She spoke with Alexie after the story broke. “I just needed to tell him how I felt and once I did, I felt better,” she says.

Alexie wrote Heart Berries’s effusive introduction, calling Mailhot “a spectacular talent.” His name is on the book’s front cover. She issued a statement at the time: “With regards to the controversy and allegations surrounding Sherman Alexie, I can speak to the fact that I always believe women and that I believe it is important to believe the women. Beyond that, I would prefer not to discuss him and to keep questions focused on my own story, art, life and Heart Berries.”

Future editions of the book will not include his introduction (or the afterword, an interview with Mailhot).

She became settled in the decision to cancel the tour – although it still picks away at her; she missed the trip home, she missed being on a panel taking place at Harvard. Then there was a day, a really good day, when the family was out having sushi and she was teaching Isaiah how to use chopsticks and she received a call. It was her publicists informing her that she was a New York Times bestseller. “It was like, everything was working. It pays off.”

As if to illustrate the point, peals of laughter emerge from the part of the room where the Caseys are playing with a toy house.

Mailhot has been living in the U.S. for more than a decade now, but keeps an eye on events in Canada. She was heartbroken over the not-guilty verdict in the killing of Tina Fontaine.

“I think it just triggered a lot for me because I had been in care at a later age in my life and I had also stayed with my auntie and I had also had a father that was murdered; he was beaten to death. So I identified with Tina’s story and I felt like a lot of native girls growing up have experiences that are similar to that or they know somebody who’s in foster care and that system doesn’t help us. We’re labelled at risk youth but then nothing’s done to protect us.”

Now she is an Indigenous woman living in the U.S. with Donald Trump as President. Isaiah goes to a school named for the Battle of Tippecanoe – where American forces led by then-Governor William Henry Harrison attacked Indigenous people who opposed U.S. expansion onto their territory, led by Shawnee leader Tecumseh. And he will go to a high school named for Harrison, who became president, celebrated for deadly military action against Native Americans – including Tecumseh. Even consider the name of the state where they live – Indiana.

“It’s a weird place for him,” Gray says.

Now Mailhot is the Tecumseh postdoctoral fellow at Purdue University, a visiting assistant professor, and is also on the faculty of IAIA.

She notes the irony of being turned down for a job at Seabird Island last year, teaching adult education on her reserve. She didn’t have the credentials.

She pays close attention to her mental health. If she needs to cancel a book tour, she cancels. If she needs to sleep, she sleeps. She doesn’t look too far ahead into her schedule so as not to overwhelm herself. She is working on a second book now, a book of essays about healing from trauma.

“I think defying the odds, it makes me want to tell people they can do it too. That no matter your circumstance, you could be in a shelter, you could be in a transitional home, you could be a single mother, you could be at rock bottom and you can still make it out,” she says.

“People should imagine good things for themselves; everyone deserves that, to imagine good things for themselves. I feel like when you come from a place of despair, often people disregard if you have big dreams. And I just feel like that’s so limiting. And I [wish] I had I given myself the permission to dream large from the start, and I think that’s where young Indigenous girls should be encouraged to do great things.”

Marsha Lederman

Marsha Lederman