Johanna Skibsrud Credit: Dan Davis Photography

In All Ages, Globe Books asks authors to dig deep for memorable books that span their lifetime, from childhood to what’s on their reading list right now.

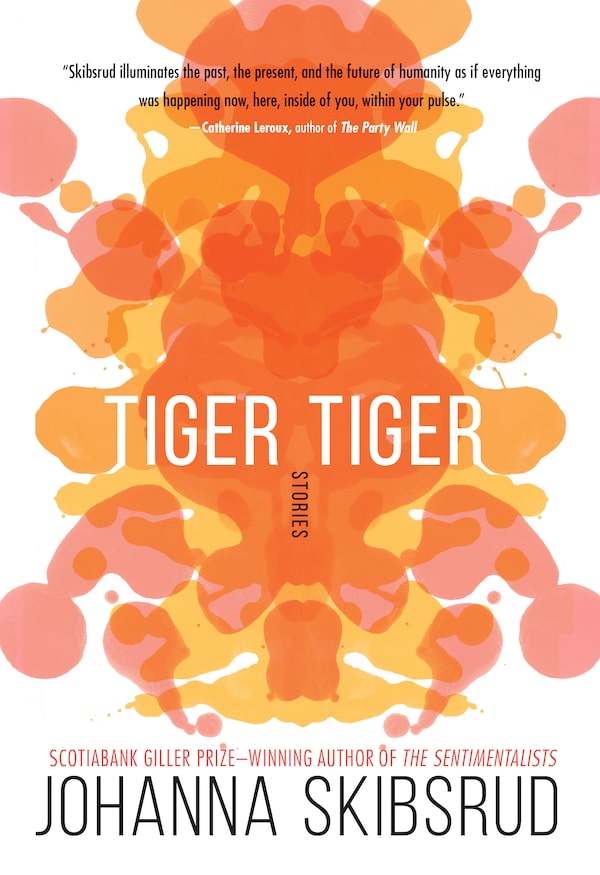

In 2010, Nova Scotia-born Johanna Skibsrud became the youngest Giller Prize winner with her debut novel The Sentimentalists. This year, she returns with her fourth book, the short-story collection Tiger, Tiger (Hamish Hamilton) with topics that range from science fiction to bloody battlefields to a fake wedding at a nursing home. Here are the many, many books that have marked different times of her life.

What did you read as a kid?

Gabrielle Vincent’s Ernest and Celestine, Barbara Cooney’s Miss Rumphius, Mary Ann Hoberman’s A House Is a House for Me.

My mother tells me that, at the age of 3, I wept bitterly when the little mouse in Gabrielle Vincent’s Ernest and Celestine lost her doll in the snow – and that later I recounted the story to my father in detail, careful not to leave out any of the sad bits. I can only guess that I recognized in this simple tale the power of stories to combine the tragic and the beautiful: to show that loss, disappointment and our incapacity to make up for the injustices of the past are finally inseparable from art, love and the promise of new beginnings. A little later, Barbara Cooney’s Miss Rumphius would teach me that even the simplest gestures – when they’re heartfelt – can change the world. And from Mary Ann Hoberman’s A House Is a House for Me (now a favourite of my own three-year-old), I learned that signs of the world’s tremendous beauty, and complexity, are literally everywhere.

What did you read in grade school?

J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit, C.S. Lewis’s The Chronicles of Narnia, L.M. Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables and Susan Cooper’s The Dark Is Rising series.

These stories, which I either read or had read to me, between the ages of 6 and 12, fed my belief in the power of the imagination. They gave me permission to see and experience the world in different ways, and they let me imagine myself as a creator of (not only an actor within) my own story.

Handout

What did you read in high school?

J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye, Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov, Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, Allen Ginsberg’s Howl.

My adolescence was crowded with the voices of unhappy men. I was drawn to the melancholic anger of Holden Caulfield and the internal struggles of Ivan Karamazov, which felt at once comfortingly familiar and thrillingly strange. In discovering the Beats, I found the perfect celebration of – as well as escape from – my own teenage boredom and despair. I wanted, like these writers, to get as far away from prescribed narratives as I could and saw in books like On the Road a continuation of the quest narratives of my early youth, as well as a resonant F-You to other people’s expectations. In Howl – which still boggles my mind with its physical energy and incantatory, almost prophetic power – I discovered the incredible aptitude of poetry to do the work of the body, as well as of the heart and the mind.

What did you read during university?

Virginia Woolf’s The Waves, Vladimir Nabokov’s Pale Fire, Roland Barthes’s Camera Lucida, Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick, Thomas King’s Truth and Bright Water, Marcel Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past.

In different ways, all of these books – read in my early 20s – expanded my sense of what writing can do. From Woolf, Nabokov and Barthes, I learned that there is no fixed line between poetry and prose, prose and thought, thought and experience, experience and its representation. From Melville and King, I learned that the best and most honest, way to tell a story is not always the easiest way. From Proust (and again from Woolf), I learned that language does not need to be read – it can wash over you in waves.

What have you read as an adult?

Muriel Rukeyser’s The Book of the Dead, Inger Christensen’s Alphabet, Clarice Lispector’s The Stream of Life, Helene Cixous’s Three Steps on the Ladder of Writing, M. Nourbese Philip’s Zong!

If I have any regrets about my reading life and its history, it’s that it took me until my early 30s to discover these books. I sometimes wonder if my life and my writing might have been different if, for example, I’d had Muriel Rukeyser as my adolescent hero rather than Sal Paradise. I love the way that all of these books imagine, in different ways, a fluidity between writing and life, the material and the immaterial, the known and the unknown. They create a space for what Rukeyser calls a “total response” both on the part of the writer and on the part of the reader. They generate a space of intimacy and encounter between self and other, what “is” and what’s only just now being imagined.