It’s in the bleak nature of things for the radical to become the regressive. Black-bloc styles are sold by H&M, Kanye stumps for Trump, Banksy shreds a US$1.4-million painting, only to double its value. Feminist writers create fraught, complex female friendships – from Cat’s Eye to the Neapolitan Quartet to Girls – as a rebuke to the flatness of so many female characters. But the barbed female friendship has turned into a trope and, in a depressing loop, its now-ubiquity makes it ammunition for the view it wanted to change: women as always and ultimately catty, petty and small. This is a flaw in our culture, rather than a mistake in the writing of Margaret Atwood or Elena Ferrante. Yet new writers of female friendship must face down this inherited problem.

The graphic novel Bad Friends by Ancco and the novel Ponti by Sharlene Teo travel the well-worn path of tangled female friendships. Released in Canada a month apart, the books have certain cosmetic similarities. Both are set in Asian cities – an unnamed South Korean city, likely Seoul, and Singapore – both feature teen-girl protagonists and both recount friendships that end in regret so acute, the leaver copes by simply putting the friend she left out of her mind.

But it is the books’ deeper, vascular likeness that sets them apart from their forebears. Redemption lines each tale, via the role of memory. Pearl and Jong-ae in Bad Friends and Szu and Circe in Ponti can’t undo what was done to them or what they did, and this haunts them. But while each is steeped in their cultural milieu, what they have to say about the regenerative possibility of friendship is so specific as to be universal. Each book offers the tender revelation that telling someone else’s story is a form of recuperation and undoing; one that is especially profound in a world that still refuses to see women.

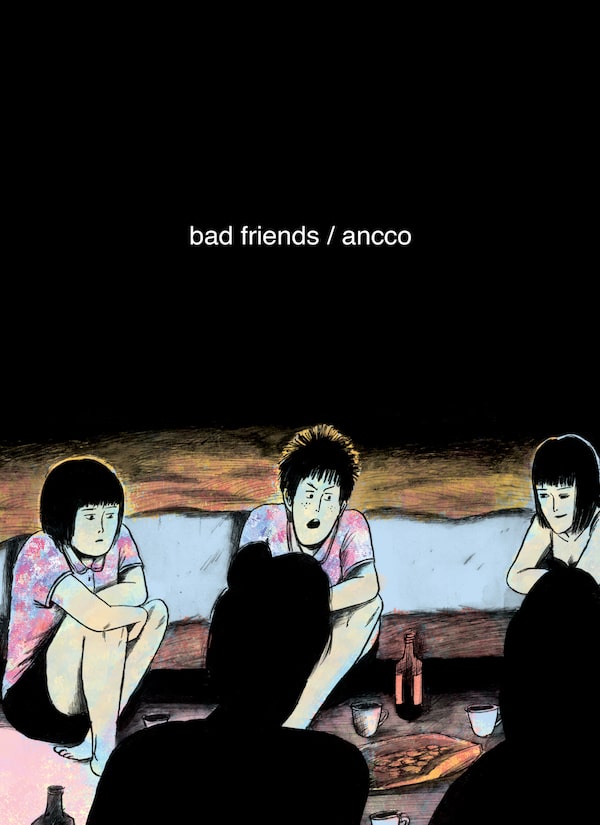

In Bad Friends – published originally in Korean and translated into English by Janet Hong – adult Pearl grieves the loss of her best friend Jong-ae, who disappeared when they were 16. Part-autobiography, and winner of both the Korean Comics Today prize and the French Prix Révélation, it is a harrowing book, almost unrelenting in its brutality. Pearl and Jong-ae are rebels and “the price they pay” for this – as the book puts it, in a painful refrain – is near-constant beatings from their parents, uncles, teachers and boyfriends. Sexual assault is a threat that swoops in more than once. When Pearl and Jong-ae run away, their only option is to become sex workers. There’s nothing they can be. Only they can see each other.

Bad Friends

By Ancco

Published by Drawn and Quarterly, 176 pages

Ancco’s art is stark, yet evocative in black and white. The contrast makes the spots of white beam brightly, like a streetlamp on a lonely city corner. The narration works through dark and light too, as it leaps from the late nineties to the present moment, where the artist examines the violence of her youth from the safety of her studio, a universe she controls. Jong-ae and Pearl are each other’s only true loves, and while they bicker, their friendship is marked more by the intensity of their platonic love than by spite. This love both tempers and heightens the anguish of the story, as when the narrative returns to a moment the friends were happy together, clowning around in a public bath. This agonizingly poignant image reappears suddenly, out of sequence, at a grim point.

What stops this novel from becoming misery porn is adult Pearl’s longing for Jong-ae. The story is hard to read because the girls are so unloved and unseen. But Pearl’s love for Jong-ae corrects this and makes it bearable. Her desire to be reconciled with her friend can only have corporeality through the being of the book itself, rather than through the physical reunion both Pearl and the reader hope for. We want to see Jong-ae step into the safety of the studio too, but this is not to be. This is heartbreaking, yet it gives us a role in the story. In reading the book, as hard as it is – just as Pearl loves Jong-ae, as hard as it is – we are letting Jong-ae be seen.

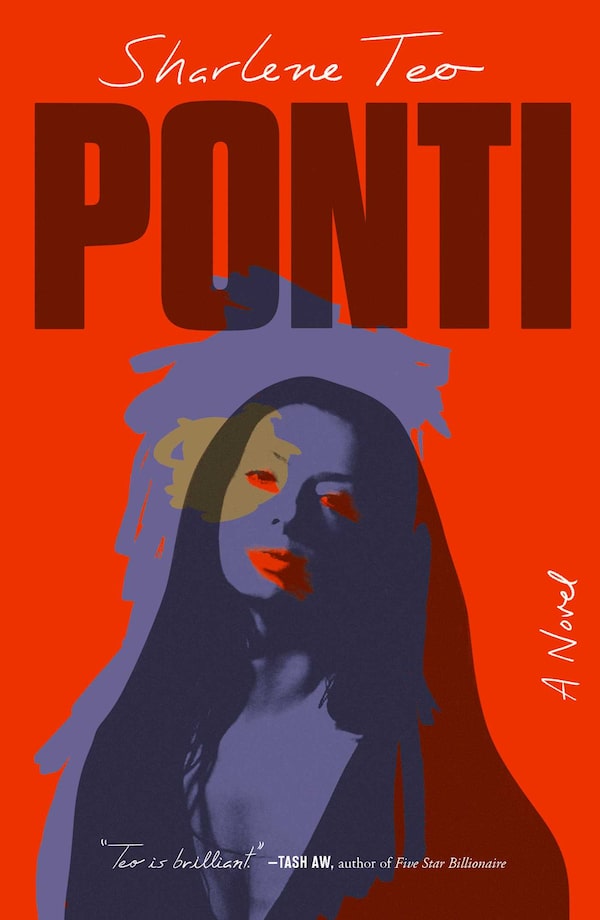

While Ponti also stars two teen BFFs, Szu and Circe, it adds a third figure to this formula: Szu’s mother, Amisa. The novel tracks their stories side-by-side: the unhappiness of Szu’s 16th year; Amisa’s earlier, short-lived seventies horror-film career, playing a pontianak (a monster of Malay lore, the ghost of a woman who died in childbirth and stalks the fields at night and feeds on helpless men); and adult Circe, trying to rationalize her shortcomings as a teenage friend. While Szu and Circe’s friendship appears to form the heart of the story – Amisa and Szu rarely appear at the same time – the novel’s power is in how Sharlene Teo plays these relationships against each other.

Amisa is a great beauty, “locally legendary … something mythic.” But whether because of the beauty or the hardness it breeds in her, Amisa’s parents are afraid of her; she is friendless and opaque, even to herself. When she wins the role of the pontianak, suddenly her life makes sense: Now she will become the somebody her face says she is. Yet when that fails, Amisa never recovers. Similar to Bad Friends, Ponti is interested in the cultural expectations placed on women, which they then internalize. Pearl asks herself, “Why did it take me so long to figure out that being beaten didn’t have to be a part of life?” In Amisa’s case, these limited options, and her inability to free herself from them, turn her into a real-world monster.

Ponti

By Sharlene Teo

Published by Simon & Schuster, 304 pages

This feminist argument is never stated outright; instead, it whispers through the pages, ultimately evident in Szu’s patient, enduring love for her mother, who does not deserve it. Szu’s willingness to love the whole person her mother is, with all the attendant disappointment, tells us that all women deserve to be seen, in context. Even Amisa, who is an abysmal mother who doesn’t abuse her daughter but merely forgets her.

But what gives Szu’s love for Amisa torque is Circe’s lack of love for Szu. Circe is given the chance to love Szu fully, as Szu chooses to love Amisa, to forgive Szu’s sad-sack demeanor, because she knows what drives Szu’s gloom. But Circe refuses these chances, both when they are teens and when they are adults. It is frustrating to watch this poor approximation of friendship. So when Szu is able to love her mother – a feat much more difficult to achieve than the one Circe never can – there’s an enormous sense of release. Circe’s failure makes Szu’s triumph all the more soothing and lightening to the reader; a joyful explosion of the belief that women are only good at griping and gossiping.

Teo writes that Szu and Circe become friends because they are both “citizens of nowhere, too gawky to be mysterious, too cautious to be wild.” Growing up in Singapore in the nineties, I would have fit right in with them. When I arrived in Canada, I was amazed to discover an entire counterculture of movies and musicians meant for outsider women like me. Julie Delpy, Le Tigre and Liz Phair, who my Canadian friends worshipped in particular. But Phair’s music spoke to my friends because they’d had the same Western experiences – suburban indie-rock boys in basements I’d only ever seen on TV. I was left cold, in a way that was even more demoralizing, excluded from the thing that was supposed to be for me.

This summer, the film Crazy Rich Asians tried to pull a Liz Phair: to offer representation to a group who’d long been left out. In some ways, the film succeeded: Newspapers and social media were flooded with stories of Asian Americans and Asian Canadians weeping in theatres. In other ways, the film entrenched the routine where some are seen, and some are not. Protests by Singaporeans that the representation of their country was white-washed and broth-thin were rebuffed and dismissed by Asian America. This is the snag with representation as a goal; it replicates a pattern. New boss same as the old boss.

Ponti and Bad Friends are thrilling because they have nothing as narrow as representation as their goal. They are not interested in telling your story, letting you see yourself. They just want to tell theirs. And in doing this, they blast the gates off. There are not two ways to be: either a Spice Girl (as eight-year-old Szu longs for, in a particularly affecting scene) or a Liz Phair alternateen. There are 1,000 ways to be. A million. Eight million. These stories liberate us to be what we are: friends, artists, monsters, mothers, human beings.

Thea Lim is the author of An Ocean of Minutes and a 2018 Scotiabank Giller Prize finalist.