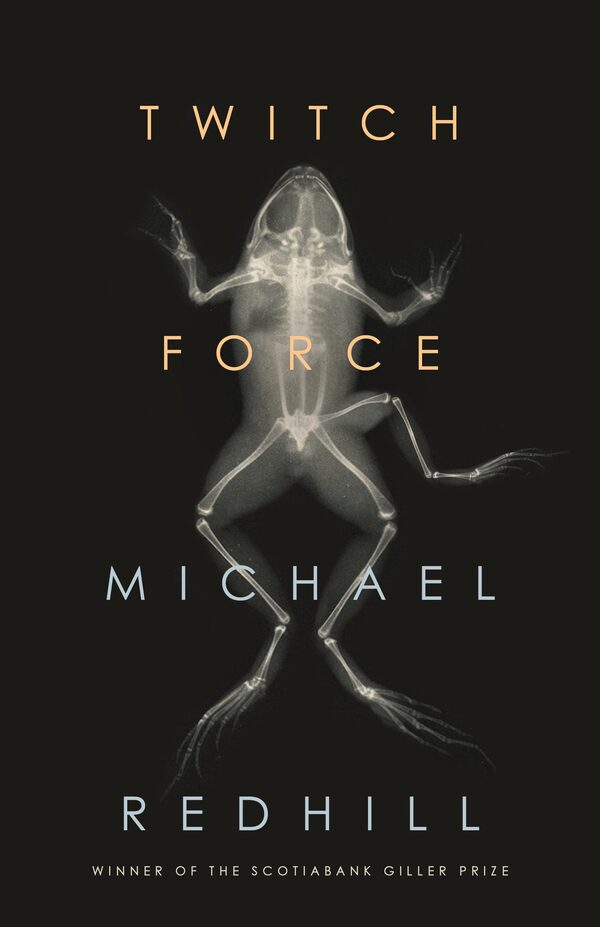

Twitch Force by Michael Redhill.

Twitch Force by Michael Redhill (House of Anansi Press, 94 pages)

Twitch Force is Michael Redhill’s first book of poetry in 18 years. But he’s been busy. Already well known as a literary novelist, playwright and editor, and as the pseudonymous mystery writer Inger Ash Wolfe, Redhill achieved new prominence with his 2017 Scotiabank Giller Prize win for Bellevue Square.

Redhill’s choice to return to poetry may seem curious to readers expecting a blockbuster follow-up. Twitch Force is aware of the expectations. A line in the opening poem, Askew, reads “I paid for the supper and I want the show. I saw my doppelganger.” A bold beginning, with Bellevue Square famous for its doppelgangers.

Redhill is still fascinated with the nature of the self in Twitch Force, a book haunted by ghostly or shadow selves. The people in Twitch Force sometimes fear, sometimes embrace these “versions of themselves” (Herculanum). In Pseudonymous – another Redhillesque bit of self-reference – he writes “I want to be as unknown as a stillborn, / buried in an unmarked grave.”

“Twitch force,” explained in an epigraph, relates to how a muscle’s previous activations influence its potential. Poems in Twitch Force often refer to physical facts that deceive or betray the people they inhabit: memory and forgetting, aging and death – the ultimate shadow.

Though sometimes the material calls for technical language, mostly the poems don’t look fancy, don’t read fancy; they are full of short, snappy sentences, quick turnarounds, straight talk, science facts, and conversational diction, not to mention bodily functions and cuss words. “Dog is like eat good. The kid is like / read and sigh. The baby is like us am.” Redhill’s poetry can be deceptively simple.

The most impressive technical action is in the sequence Scar Tissue. A well-versed poetry reader will recognize some of its lines and phrases. Other lines might feel like ghosts of half-remembered words. The notes explain: much of the sequence is made of borrowed fragments. It’s a poetic enactment of, Redhill explains, “a constant cycle of wreckage and re-creation,” an idea credited to biomedical engineer Dr. Glenn Prestwich and collaborators. Redhill directs the reader to his website for the complete breakdown of borrowed lines. Scar Tissue is seamless despite its under-the-surface complexity. Not only did Redhill write it from fragments, he wrote it in syllabics, and he wrote it for performance with music by Jeffrey Ryan, for six voices and piano trio. It premiered in February.

In Four Poems from 1988, Redhill has (apparently) revisited poems first written 30 years ago, conversing with another version of himself. In it, a speaker contemplates death while at a concert:

The head a concert hall filled with echoes, one thought pulled tight as drumskin. I listened until they turned the lights out. The performers were a shadow of sound and we remembered them in the dark.

The poems of Twitch Force are nothing if not dense: death, shadow, multiple voices, and memory show up in those five lines alone. Compression is Twitch Force’s natural state, poems ready to pounce.

The Caiplie Caves by Karen Solie.

The Caiplie Caves by Karen Solie (House of Anansi Press, 118 pages)

A new Karen Solie book is a poetry event. The Saskatchewan native is one of Canada’s most renowned and accomplished poets. But even in the context of Solie’s stellar career – which has included winning the Griffin Poetry Prize for Pigeon – her fifth book, The Caiplie Caves, is a significant achievement.

The Caiplie Caves represents a gentle departure for Solie. It’s much more a book-length project than a collection. The Scottish caves of the title, once inhabited by a seventh-century religious hermit named Ethernan, don’t immediately sound like a stimulating concept. But in Solie’s virtuosic hands, the material becomes fresh, vigorous, crucial, and contemporary.

Geographically and historically, Ethernan’s hermitage is a loose starting point, a place the book returns to, but doesn’t remain in. The caves form a dynamic heart, or an engine: the site of a moral problem, or a moral “error,” powering the book. Solie gives the historical context in her preface. Ethernan, some scholars believe, needed to choose between “a hermit’s solitude” or establishing a community on the island looming across the water in the Firth of Forth: May Island, with its “may” full of potential and uncertainty. A speaker, presumably Ethernan, contemplates the island from his lonely position in the caves:

I offer cold, the season working as it should loneliness, love working as it should pain, the body working as it should and failure a thought indulged in isolation is almost certainly an error and May the plus-minus sign (“Now blood on his lip…”)

This island, a manifestation of uncertainty, returns again and again in the poems, as does the does-not-compute “error.” “Every choice is a refusal,” Solie writes in “When Solitude Was a Problem, I Had No Solitude.” When a choice is made, something else is lost. She deftly mines Ethernan’s moral struggle for all the modern dilemmas it suggests, his questions rippling from his cave through the speakers, eras and locales in other poems. “Usefulness” – and environmental degradation? Or retreat – and abdication of responsibility? Does it have to be one or the other?

“[If] one asks for a sign / must one accept what’s given?” asks the version of Ethernan in Like Cormac Ua Liatháin, he sought… This is poetry painstakingly built for asking questions, not answering them. “I wanted an answer, not a choice,” continues the speaker in the same poem.

The Caiplie Caves is a work of impressive layering and depth, full of call-backs, interweaving, careful research and textual references. Solie cites critical theory and mysticism, scripture and field guides, philosophy, theology, history – and a text message from poet Ken Babstock. Each reading reveals new connections and new questions.

Solie’s poetry in The Caiplie Caves offers ambiguity in response to those questions, an ambiguity not fuzzy, but deliberate and clear. Uncertainty not merely an error, but a truth of the world.

Dunk Tank by Kayla Czaga.Handout

Dunk Tank by Kayla Czaga (House of Anansi Press, 96 pages)

Kayla Czaga’s Dunk Tank caps off with a multipage poem called Mosquitoes, in which Czaga writes:

I am still writing this cliché Canadian shit. I am writing dogwood and diaspora along the lonely shoulders of Coastal mountains. Sorry I’m so boring.

It’s a fanciful statement: the book contains poems about, for instance, vending-machine dinosaur erotica and hell-hounds hidden in Winona Ryder’s skin. But the “still writing” and the tongue-in-cheek apology point to Czaga’s decision to deal directly with the spectre of second-book blues in Dunk Tank. Directness is a chief attribute of these poems. They flaunt their existential search for what is even worth writing about among the transience, triviality and deprecation in the world.

Czaga left the northern town of her childhood – Kitimat, B.C., a central landscape in her work – for university, and from there entered the poetry scene with For Your Safety Please Hold On, which went on to be shortlisted for a Governor-General’s Literary Award. As with her 2014 debut, Dunk Tank trades in specificity, intimacy, weirdness, colloquialism and dark humour, but with a natural pivot in subject matter.

While From Your Safety focused on childhood and family portraits, Dunk Tank offers a young woman’s dazed suspension in the nether-land of not knowing what’s going on. It’s a book about the absurd choices and non-choices on offer in a world bent on preventing real adulthood – whatever that is – now more than ever.

In the title poem, Czaga describes an addressee suspended in mid-air as she descends toward the dunk tank’s water: “you’re sitting / on nothing,” she writes, “and you think maybe / you won’t fall after all—maybe / you’ll just hover here forever.” In Money, the speaker is similarly paralyzed when “the feeling of really / living” hits her “like a ghost elephant."

The apparent youth of the poems’ speakers points to millennial angst, but it’s more than that. In Dunk Tank, everyone is hurtling toward an inevitable death, but they hurtle with humour, shrugging their shoulders at the meaninglessness of it all, just getting on with the poems. Bugs fly through often, such as in Tender Like Beverly Tender:

The first part of my life was a prehistoric bug. The second part was a second prehistoric bug. More life, more bugs crushed on the windshield. …

The speaker might feel like a bug squashed on a cosmic windshield, but the splash pattern is far from boring. Czaga’s humour, specificity, no-nonsense diction and contemporary language keep all the death and disquiet hanging together. The voice is self-conscious, but in a clear-sighted way. “I am only beginning / to find something I can move around / in and call my voice,” Czaga writes in If I Had to Feel the Same Again I Would. “It’s hairy / and complicated.”

Second-book blues? Whatever. Czaga’s vocal hairiness is a welcome cultural complication.