The books arrived at the best of times and the worst of times. The worst because I had just returned from an exhausting trip to be confronted by two piles of books – one that needed to be read for my job; and a second, largely untouched, that I had hoped to read for pleasure over the summer. Adding to either stack seemed foolish, futile and anxiety-producing.

But these new books – they demanded to be read. While I had been away, the new artistic director of the Vancouver Writers Fest had told me about a “living autobiography” by the British novelist and playwright Deborah Levy. And here they were next to my front door and my giant, yet-to-be-unpacked, suitcase.

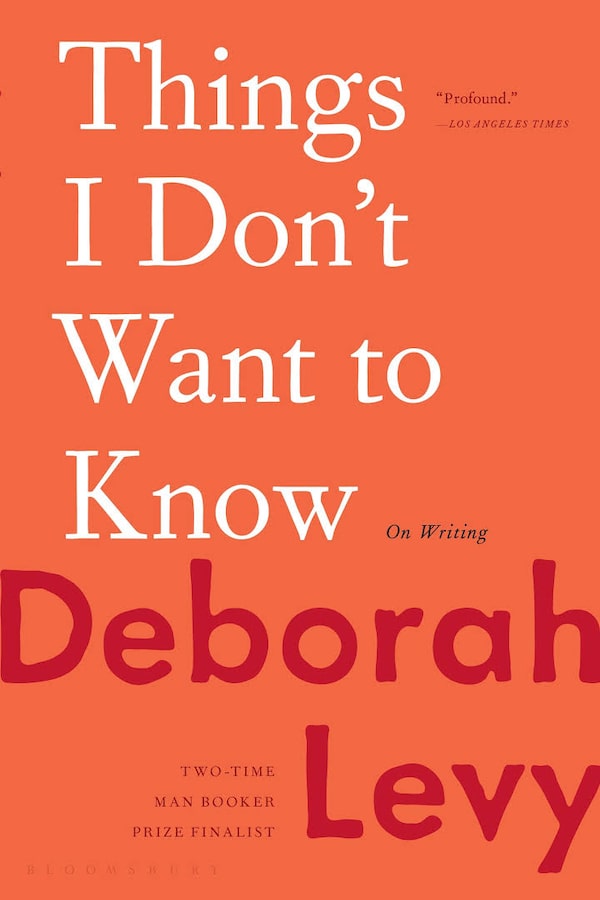

Jet-lagged, I dragged the first of the two I had been sent (the third is yet to be published) to bed. I was exhausted and needed to sleep; it was back to work in the morning. But I started reading Things I Don’t Want to Know, the first in the trilogy, and I couldn’t stop.

South African-born British playwright, novelist and poet Deborah Levy is seen at the Edinburgh International Book Festival.Colin McPherson

The books had arrived at the best of times because, my God, could I relate.

These meditations on writing and womanhood, written by a woman during (an unexpectedly chaotic) mid-life, had landed on my doorstep at a time when I feel as if almost every woman I know is dealing with something gigantic that has led to much self-examination and soul-searching, many difficult conversations and a lot of wine consumed among girlfriends. The worst of times.

The Enthusiast: Why aren’t you watching HBO’s brilliant Succession?

Things I Don’t Want to Know begins with Levy crying on escalators for reasons unknown, and takes us into her difficult childhood in South Africa, where her father is arrested one night after they build a snowman together and spends years as a political prisoner. It is also very much a contemplation of what it means to be a contemporary woman.

“Now that we were mothers we were all shadows of our former selves, chased by the women we used to be before we had children,” she observes in the playground. A couple of pages later, she writes, about the plight of the modern woman, “If we felt guilty about everything most of the time, we were not sure what it was we had actually done wrong.” And then this: “We had a go at cancelling our own desires and found we had a talent for it.”

I am precious about my books. They are alphabetized on my shelves and for non-fiction, arranged according to categories. I do not mark them up. I like them pristine. But this pair, which I started and finished in a period of two-and-a-half days, demanded a pencil for underlining. And when I couldn’t find one – screw it, I thought; I used a pen.

I paused my reading only to go to work (and the bathroom) and to tell every woman I know that she must read these books, which are also rich with literary references. Go directly to the bookstore; do not pass Go, I would say, employing my overused Monopoly joke that most people don’t get (or don’t find funny).

The second book, The Cost of Living, deals more with Levy’s contemporary circumstances: the picking up of the midlife pieces as she sells the family home, rents a substandard flat and sets to work writing in a bone-chilling shed so she can put food on the table for her daughters. Also, her mother is dying.

“When I was around fifty and my life was supposed to be slowing down, becoming more stable and predictable, life became faster, unstable, unpredictable. My marriage was the boat and I knew that if I swam back to it, I would drown.”

Comparisons to Karl Ove Knausgaard seem inevitable, given that he too has mined his life for a series of literary memoirs. I admired Knausgaard’s wildly successful autobiographical novels, collectively titled My Struggle, but gave up on the series three books in, a little tired of the long-winded self-absorption. Levy’s books are slim, but no less wondrous; she packs astounding insight and clarity into every passage. Is it a man-woman thing? Maybe; one of Levy’s themes is that men take up too much space.

She observes that women can be neglected, exhausted, unloved but still manage to create functional homes. As she writes, “it is an act of immense generosity to be the architect of everyone else’s well-being.” Then there’s this insight: “There were many modern and apparently powerful women I knew who had made a home for everyone else, but did not feel at home in their family home.”

I could go on and on, typing out sentences I underlined with the forbidden pen. If I could, I would buy these books for every woman I know. In the meantime, I can text them choice passages.

“Life falls apart. We try to get a grip and hold it together. And then we realize we don’t want to hold it together” is one favourite.

Or this one: “Chaos is supposed to be what we most fear but I have come to believe it might be what we most want.”

Marsha Lederman

Marsha Lederman