Author Steven Price.Handout

He lived in a world of decaying villas and all-night parties, a world trying to forget the horrors of a war only 10 years in the past. It was Italy in the age of La Dolce Vita, Italy in the late 1950s.

His subject was change, meaning time, meaning loss. He himself had lost everything. He lost his mother to the war’s shadow, his childhood palazzo to the bombing of Palermo, his father’s wealth to the courts. It is no wonder he did not trust the stability of things, that anything could remain as it was. Everything was always, it seemed, in the process of becoming something else.

He was a sad, shy, overweight man, who walked too slowly, who smoked cheap cigarettes between stained fingers, who was careful with the threadbare knees of his trousers. In the streets of Palermo, he could be seen carrying a small black bag with a volume of Dickens in it and a bag of pastries on top. He looked 20 years older than he was.

Literature was his one consolation. He lived his whole life inside novels and at its very end, he sat down and wrote one himself. That novel would prove to be a masterpiece. It would win the Strega Prize; it would be celebrated around the world; it would come to be considered the greatest Italian novel of the century and never go out of print. And yet, Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa, last prince of Lampedusa, died destitute and in despair, believing The Leopard would never be published.

The Leopard tells the story of Don Fabrizio, Prince of Salina, as he lives through the upheavals of late 19th-century Sicily, witnessing the dying out of the old feudal order and the birth of a unified Italy. Don Fabrizio is a man spiritually adrift, for whom all the old certainties are gone. The novel’s imagery is vivid, sensuous: the dusty carriage journey out to the countryside in the summer heat, the moth-eaten skin of a once-beloved family dog hurled in disgust from a window. And its characterizations are quick, sharp: Lampedusa’s portrait of his prince gave rise to one of Burt Lancaster’s greatest performances, in Luchino Visconti’s ravishing 1963 film. The Leopard has stayed in the memories of its admirers for more than 50 years.

I myself came to The Leopard for the first time in my early twenties, a young writer startled by its gravity and grandeur. I did not then imagine I would some day write a novel in response; The Leopard felt too remote, too severe. It was a novel set against a dying world, filled with regret and longing. But the elegiac tone that moved me then is not, powerful as it is, what stays with me now. Like any masterpiece, The Leopard changes as its reader changes; what we find in it is, in part, what we become.

Late in my writing of Lampedusa, I travelled to Sicily to research the world of Giuseppe Tomasi. I found his ghost everywhere. I stayed in a room adjoining the palazzo where he lived out his final years with his formidable wife, Alexandra von Wolff-Stomersee. Nightly, I heard the hollering of families in the balconies nearby, the church bells ringing the hours. In the mornings, I walked the hot streets of Palermo, from café to café, following the very path Lampedusa once took.

And I travelled overland to Palma di Montechiaro, tracing Lampedusa’s own journey from the fall of 1955. I, too, toured the town’s church and convent, dedicated by the ancient Tomasi and I, too, drifted among the stones and long grasses of the Tomasi castle, on a cliff high above the sea, taking furious notes all the while.

One afternoon in Palermo, I met, to my amazement and delight, Gioacchino Lanza Tomasi, the adopted son of Lampedusa, and his wife, Nicoletta, who took me on a tour of Lampedusa’s palazzo. “He was a man completely in despair,” Gioacchino said. “He had the idea of the memories of things.”

When it was first published in English, the novelist E.M. Forster sensed this also, observing of The Leopard that it was not a “historical novel,” but rather “a novel which happens to take place in history.” What he could not have known then was that, in the delicacy of its handling, in the careful illustration of a prince facing his own decline and increasing irrelevance, The Leopard would continue to live on, even into the digital age. It is perpetually of the now, perhaps because every age is an age in flux, an age of crisis. If its subject is change, it is also about how we accommodate change, or fail to do so.

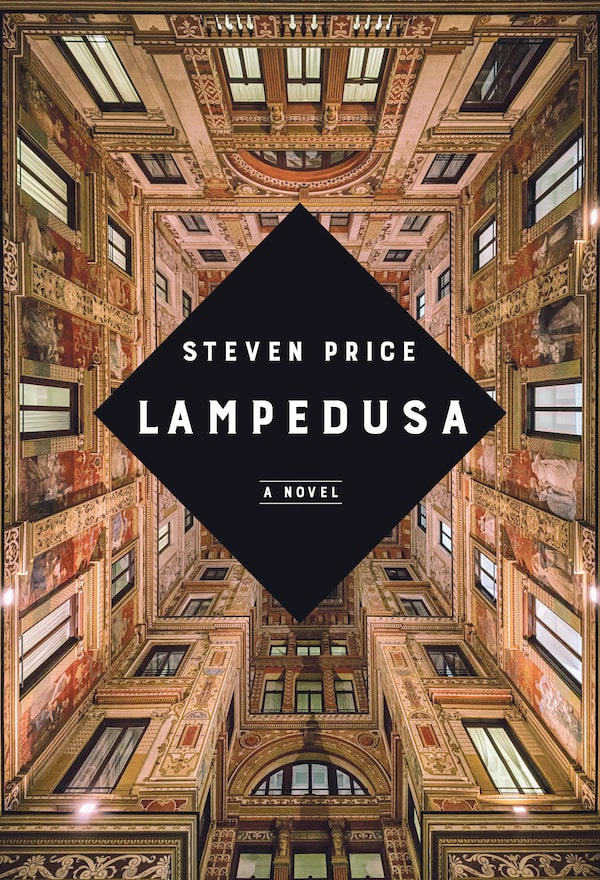

Lampedusa is available Aug. 27.Handout

Sixty years after The Leopard’s first publication, the world wars are fading, their terrible destruction seen only in old newsreels. But our world is not so very different. Ours, too, is an age of upheaval and loss. People once again are looking back to an imagined golden age, alarmed by the changes going on around them, fearing for their place in a world that seems to have left them behind.

Lampedusa wrote directly to such fears, suspicious of just that sort of nostalgia. His novel is ambivalent about power and human frailty in part because he understood the nature of his own diminishing. He had lost everything in the war; he could easily have lost himself too, in bitter fantasy, reminiscing about the beautiful years. But he remembered clearly not only what he had lost, but also how imperfect it had been. He refused to absolve anyone, himself included.

Was he more alive for the past that moved within him or less so? When I understood that his life mirrored the very structure of The Leopard, I began to see a way into my own novel, Lampedusa. It would be a story about his writing of The Leopard, certainly, shaped around a man for whom the old certainties had gone, set in a sun-drenched Sicily. But it must also be about memory, and loss, and our capacity for change.

For I came to see, as I wrote, that Lampedusa had imbued his fictional prince with his own ambivalent faith in the human condition. What stays with me now, more than any other aspect of The Leopard, is Lampedusa’s sensitivity to the complicated workings of the human heart. We are changeable creatures, he seems to be saying. And that is reason to hope.

Lampedusa is available Aug. 27 from McClelland & Stewart

Expand your mind and build your reading list with the Books newsletter. Sign up today.