Drawn & Quarterly

- Title: Clyde Fans

- Author: Seth

- Genre: Fiction

- Publisher: Drawn & Quarterly

- Pages: 488 pages

- Price: $64.95

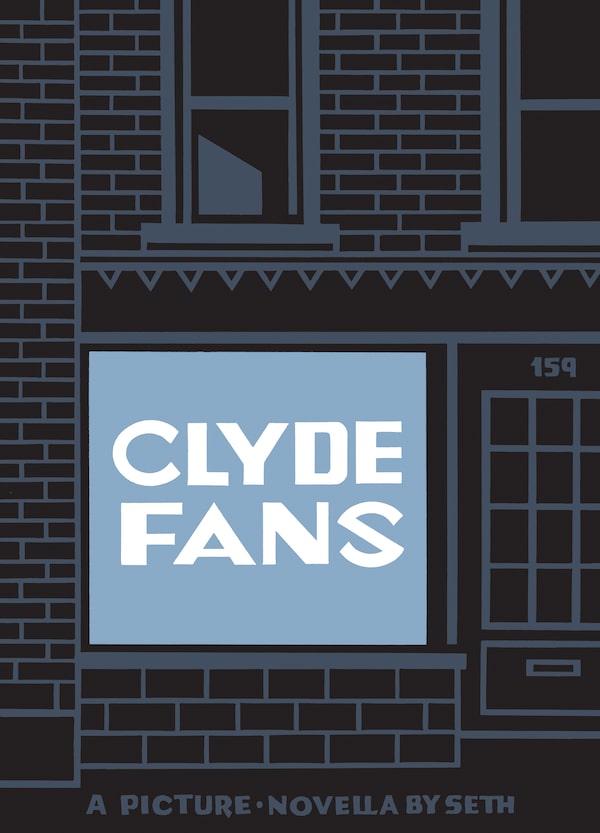

The front cover of cartoonist Seth’s massive, virtuosic new book presents the view of a simple storefront, dominated by a picture window. The words emblazoned across its glass – Clyde Fans – are at once the title of Seth’s magnum opus, the name of the Toronto business diffidently operated by the two brothers at the centre of his tale and the building in which they wind out long, slow years of their lives. The cover is die-cut, so that the window quite literally invites us to peer into the world that waits behind the glass – a frozen and isolated time and place, where objects exist in suspended animation, where little stories await the chance to come to life.

Seth's Clyde Fans is set in the 1950s.Drawn & Quarterly

In Clyde Fans, Seth profoundly, boundlessly imagines what goes on behind that storefront window. The artist has been crafting the tale since 1997, when its first pages are set, and the monumental time that has gone into completing the involuted saga of Abe and Simon Matchcard is layered into the work. While the brothers take turns looking back over the twin failures of their business and their lives, time’s passing becomes at once the book’s subject and its substance, as we see Seth’s cartooning style mature from willowy lines and flowing sentences into more geometric and abstract forms, and telegraphic, staccato narration. As the brothers reflect on the mundane mistakes of decades past, the decades that Seth himself invests in their hermetic world become more and more visible, and more and more meaningful.

The quaint period details that Seth evokes can easily seduce the reader.Drawn & Quarterly

As the book begins, the story has already ended. Abe Matchcard, the older brother, now a reclusive old man, wanders the threadbare premises of what was once the family business, as well as the private residence of younger brother Simon. Abe delivers a soliloquy that’s part salesman’s palaver, part potted family history and part doddering philosophy, hinting at the troubles that the rest of the book draws out. Most significantly, there’s querulous Simon’s ill-fated 1957 sales trip to the Northern Ontario metropolis Dominion, which Seth relates in extended, bravura flashback sequences, laying out the mundane geography of the imaginary city almost as closely as the intricacies of Simon’s frail psychology. Where Abe can be hard-bitten – a philanderer and strike-breaker, at one point he packs the boys’ senescent mother off to a home despite Simon’s reluctance – Simon is a soft touch, a devoted son and diligent hobbyist, for whom this single mortifying trip distills the ways in which the world outside Clyde Fans becomes unbearable.

The Clyde Fans building is more than a business for Simon. It’s also a storehouse of memories and resentments, foreclosed opportunities, or better futures that failed to materialize. This is nowhere more apparent than when Simon, after watching his beloved mother losing the battle with dementia, spends pages on end cataloguing the knick-knacks that adorn her room. Seth has always masterfully conjured atmosphere and mood – longing, reverie, even enervation – but here he achieves a new emotional heft. As Simon enumerates the toiletry jars, ladies’ gloves and cheap figurines of his mother’s boudoir, so much close and exacting attention becomes overwhelming and heart-wrenching, as though the son could resurrect the mother and render her whole through these tawdry parts.

The surfaces of his designs give way to chilly depths.Drawn & Quarterly

It’s easy to be seduced by these kind of quaint period details that Seth so ably and lovingly evokes – dime-store novelty postcards and tin toys, sturdy mid-century electric fans, the hefty rubber stamps and ledger books of bygone storefront offices. And in his highly visible work as a designer, creating covers for the Criterion Collection’s classic Hollywood comedies or illustrating books for Stuart McLean and Stephen Leacock, his riffs on Art Deco or mid-century Modern or Diefenbaker-era Canadian schmaltz can come off as merely charming, or wistfully nostalgic.

In his mature work, however – among which I would certainly rank Clyde Fans, as well as George Sprott, his New York Times-serialized story of a polar explorer-cum-television host, and his pseudo-autobiographical classic debut, It’s a Good Life If You Don’t Weaken – the dazzling and often tongue-in-cheek surfaces of his designs give way to chilly depths.

As our lives plunge on, Seth creates a respite from the maelstrom of ruined relationships, crumbling mementos, mouldering paper and dusty old fans.Drawn & Quarterly

Seth can get pigeonholed as a nostalgist, but this assessment fails to make a distinction between mourning times past and lamenting time’s passing. You might mistake his fascination with the erstwhile and antiquated as a desire to have it all back again and return to those halcyon days. But for Seth – as for Abe and Simon – the past is fascinating not because it was better, but because it is so irrevocably gone. To dwell in the past, as Abe and Simon do for nearly every tightly drawn and paced page, is to be fascinated with our own mortality, to watch the wreckage of time continue to pile up behind us – ruined relationships, crumbling mementos, mouldering paper and dusty old fans – as our present-day lives plunge on. In the still, sad, silent heart of Clyde Fans, Seth creates a respite from this maelstrom.

Seth talks about his inspiration for his new book

I was 18 years old when, in 1980, I first arrived in Toronto by train. Up through the labyrinth of Union Station, out into the traffic of Front Street – there to be dazzled by the enormous Royal York hotel looming over me – a vivid blue sky beyond it. This was the big city. My first experience of it.

This grand metropolitan vision wasn’t to last long, though. In short order, it was replaced by a more modest image of the city. A brown and grey street-level view of urban life. In those days, something of the 1950s still hung over Toronto – a place of little neighbourhoods, streetcars and depression-era brick buildings.

I came to Toronto to go to the Ontario College of Art and it was that routine walk along Queen Street, from Parkdale to McCaul and back again, where I first took notice of the humble storefront businesses. Printers, hairdressers, haberdashers, fabric jobbers, repair shops, dry cleaners, stationery stores, greasy spoons – an almost endless catalogue of the small places that make up city life. Over the next two decades, I saw most of them disappear and witnessed a newer city rise up. A much shinier, much busier and, perhaps, a somewhat less cozy city.

I’m no photographer, but around the late eighties or early nineties I began taking snapshots of some of these old storefronts as reference for my drawings. I glued them in scrapbooks and barely gave them a second thought. However looking at these photos today, they remind me how human-sized these old businesses were: the warmth of wood and brick and tile and stainless steel. You don’t realize it but the environment of your youth gets inside you and when it’s gone you can’t help but miss it.

All this is a rather roundabout way of explaining why I spent so many years imagining a graphic novel out of an old decrepit storefront that I used to pass on King Street. The Clyde Fans business is long gone now, though I could still easily point out where it was. It has joined a thousand other vanished businesses. Most are forgotten, but some linger on. Over time, we all build a kind of city of memory inside ourselves.

Expand your mind and build your reading list with the Books newsletter. Sign up today.