Dr. Carla Fry and Dr. Lisa Ferrari had a simple plan. The Vancouver registered psychologists and co-authors of Gratitude and Kindness: A Modern Parents Guide to Raising Children in an Era of Entitlement wanted to give children an opportunity to experience the impact of performing random acts of kindness.

So three years ago, Fry and Ferrari organized their first annual “Kindness Patrol,” gathering children to hit the streets and do nice deeds for others, such as giving out handmade cards to unsuspecting strangers.

What they didn’t anticipate was rejection. When the children offered flowers to passersby along the Seawall last year, many people refused to accept the gifts and stepped away, leaving the children confused and crestfallen.

“The most common first reaction of the random public out there is mistrust: ‘What do you want to sell me? … Why are you doing this? There’s no possible way you could be giving me something with no strings attached,’” Fry says. “We live in a world where there’s only patchy kindness sometimes.”

Yet, lately, there seems to be a hunger for more of it.

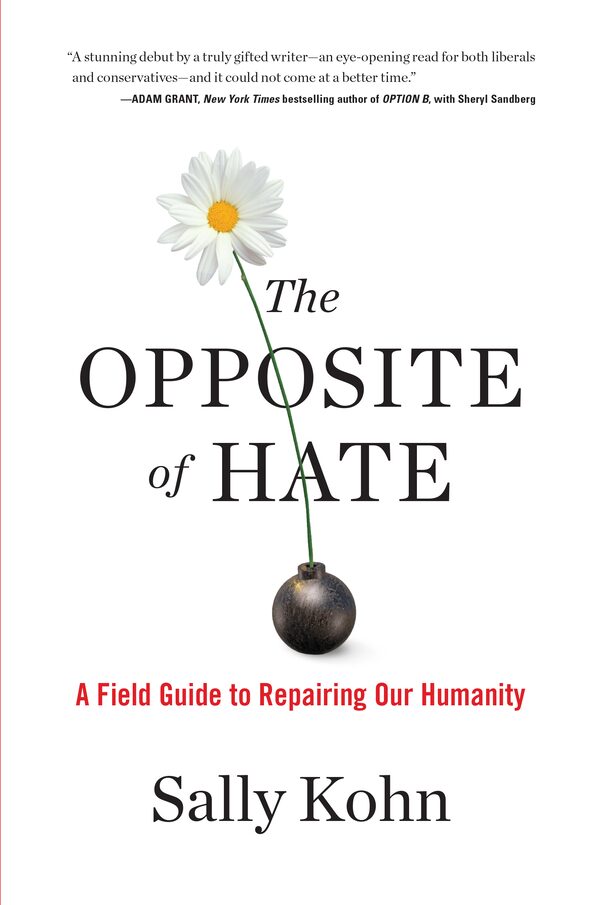

handout

Two new books, The Power of Kindness by Dr. Brian Goldman, and The Opposite of Hate: A Field Guide to Repairing Our Humanity by Sally Kohn, suggest we’re at a low point in terms of treating each other well. We’re quick to judge others, we hurl unspeakable insults at each other online, and we don’t think twice about mocking or dismissing those who have opposing views.

To explore how we got here and how we can be nicer, Goldman and Kohn set off on opposite paths. Goldman, a Toronto emergency-room physician and host of CBC Radio’s White Coat, Black Art, travels the world in search of the kindest individuals to find out what makes them tick. Meanwhile, Kohn, a CNN political commentator, reaches out to people who’ve committed or expressed extreme hostility, including online trolls, an ex-white supremacist, and participants of the 1994 Rwandan genocide, to learn what made them hateful. The conclusion they both reach is essentially the same: to be kind, we need to connect and empathize with others.

Is it that hard not to be a jerk? After all, even the youngest participants of the Kindness Patrol understand it doesn’t take much to be nice. “Kindness doesn’t cost a thing,” Fry says. “It’s pretty easy to do if you just try.”

The problem is it’s also easy to behave badly. As an extreme example, Kohn recounts meeting an ex-white supremacist named Arno Michaelis, who told her he didn’t hold racist views until he became drawn to a racist punk band.

“Could listening to the wrong music at the wrong time have turned him into a committed, violent racist?” she asks incredulously, before answering in the next paragraph: “The more I learn about the nature of white-supremacist groups, the more I realize how plausible Arno’s story is – that such random indoctrination is actually rather common.”

Of course, one needn’t become a white supremacist to participate in the dehumanizing and demeaning of others, Kohn tells The Globe. “We all do it. We are all doing it right now.”

She is frank about her own shortcomings and implicit biases. She freely admits, for instance, to favourably stereotyping white people over black people and men over women – a knee-jerk reaction shaped by deep-rooted societal prejudices. And she argues that only by acknowledging and recognizing our own hate can we begin to counter it and see the humanity in others.

Ironically, her message that we’re all fallible, herself included, has been brought into relief by a dispute played out on social media over Kohn’s use of two sources in her book. Aminatou Sow, co-host of the podcast “Call Your Girlfriend,” has said on Twitter she does not remember saying what Kohn attributed to her in the book, and that Kohn did not ask for permission to quote her. Writer Ijeoma Oluo has also taken issue with Kohn on Facebook, saying that Kohn recounted a Twitter exchange between Oluo and an online troll in an extremely negligent way. The passage takes Oluo’s work out of context and does not reflect her philosophy on dealing with racist hate, Oluo states. These incidents have been raised by Sow and Oluo as examples of offences borne out of Kohn’s privilege as a white person.

In a statement she shared on Twitter, Kohn apologized to Sow, saying that, while she did ask for permission to quote her, she was sorry for hurting and upsetting Sow and welcomed “every opportunity, no matter how painful, to be challenged” on her blind spots and privilege.

From Kohn’s view, reconciling differences among opposing camps, whether it’s a domestic political fight or genocide, requires recognizing that people do horrible things, but that these things do not make them horrible people.

“If you want a constructive way forward, it seems to me that’s the only possible mindset that works. It also has the benefit of being true,” she says.

Clashes, however, are rarely set aside so tidily. The controversy that continues to shadow Kohn over her treatment of her sources provides a case in point. And the idea that victims need to forgive their offenders is a deeply uncomfortable one. Knowing that any of us has the capacity to hurt others doesn’t make the hurt any less painful.

Kohn acknowledges this point in her book, writing, “There is something inherently unjust in suggesting that the burden to turn the other cheek should so often fall on those who have been hit hardest.”

But she argues that when we condemn others as “evil,” we hem ourselves into a corner. “Where the hell do we go from there?” she says. “There’s no answer to that. There’s no solution. There’s no prevention. There’s no reconciliation. There’s nothing. You’ve said, ‘That’s evil.’”

If everyone has the capacity to act heinously, Goldman draws upon neuroscience to suggest humans are also generally hard-wired to be empathic and kind.

“Without empathy, without that, we would constantly be at war with our neighbours and countries would constantly be at war with their neighbours, and we would have probably blown each other up ages ago,” he says. “So it’s baked into our DNA and our brain circuits.”

In The Power of Kindness, Goldman’s search for extreme kindness leads him to meet a Tim Hortons franchise owner in Toronto who employs and advocates for people with disabilities, the co-owners of a Manhattan pub that became a hub for emergency response workers after the Sept. 11 attacks, and a woman in Sao Paolo who befriends a homeless poet and reunites him with his family.

The individuals he profiles are undeniably empathic. It’s a pity, though, and an indictment of our society that hiring individuals with disabilities or connecting with those who are homeless should be considered exemplary, instead of ordinary.

Through his encounters, Goldman concludes that some people are simply born kind, and others are empathic because the setbacks they’ve experienced in their own lives have given them a better appreciation for others who are struggling. But kindness and empathy are a choice, he says – a choice between your own needs and your instinct to help other people.

“So if you create the conditions in which empathy and kindness can flourish, then it’s more likely to flourish,” Goldman says.

This is not an area Goldman explores deeply in his book, but he explains to The Globe there are multiple ways in which our society and lifestyles make it difficult to choose to be kind. It’s almost impossible to empathize with others, for example, when we’re being shamed on social media, or when we’re burdened by stress, he says.

To create a kinder society, “probably the most basic thing we can do is reduce the amount of stress in our society by making sure that people have enough to eat, a sense of purpose, better education, better access to education, clean air, clean water, a safe neighbourhood,” he says. “All of those are the most basic building blocks, and they’re not just of kindness, but of general health.”

It also helps to have leadership that models kind behaviour, and to slow our lives down so that we can develop stronger connections with one another, he adds.

To achieve all of this seems insurmountable; it’s no wonder our world is so often callous and hostile. But Fry, the co-creator of the Kindness Patrol, offers a silver lining.

“A person who’s received kindness is more likely to give kindness,” she says. (She has since learned to better prepare the children for less-than-appreciative reactions, and sees the previous negative responses as a sign that more Kindness Patrols are needed.)

“It does grow.”

Wency Leung

Wency Leung