Samra Zafar poses for a portrait at the University of Toronto student activity centre Hart House on Feb. 27, 2019.Annie Sakkab/The Globe and Mail

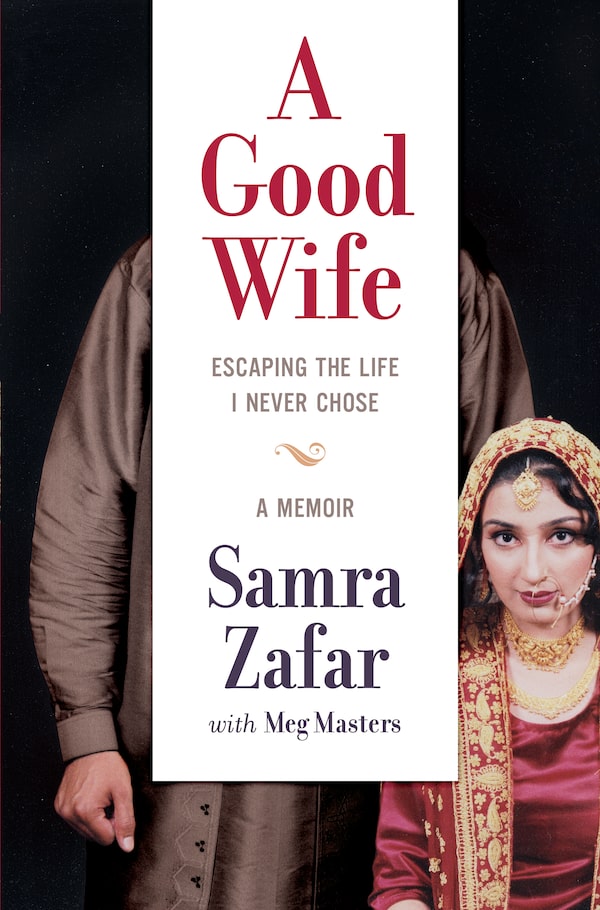

A Good Wife, Escaping The Life I Never Chose by Samra Zafar.Handout

A blizzard rages outside a boutique hotel in midtown Toronto. Cars crawl through snow-covered streets. And in walks Samra Zafar, dressed in a light wool jacket. No hat. No gloves. Underneath, she wears a business suit. Her legs are bare. On her feet? High-heeled evening sandals.

Bare legs and high heels in a snowstorm?

“Guess I’m just a badass!” she crows, kicking out one leg to show off her defiance of winter.

She sits down, smooths her long, dark hair with one hand, pushing it to fall across one shoulder, and looks across the table like an executive about to chair an important meeting. She has been her own prince in an astonishing Cinderella story, rescuing herself from an abusive marriage, arranged for her by her family in Pakistan when she was 16. She married a stranger 11 years her senior and moved to join him in Canada. For 12 years, she endured abuse, living with repressive in-laws, forced to wear a hijab and restrained from pursuing a life outside the home. Eventually, by making money with home-based jobs, she saved enough to pay for courses at University of Toronto Mississauga. The family agreed to let her attend school but kept close watch of her movements. With the support of professors, counsellors and fellow students, she found her way free. The greatest insight into her plight came from a social worker who told her that the abuse was not her fault.

Winner of several scholarships, an international speaker, bank executive and one of the youngest member of University of Toronto’s Governing Council, the single mother of two teenage daughters, now at 36, is a far cry from the sad young woman she describes in her memoir, A Good Wife, Escaping The Life I Never Chose, which appears in bookstores March 5.

As a young girl, you were ambitious; focused on going to university. Do you look back and wonder why you agreed to this arranged marriage?

In my naive 16 year-old head, I was just going to university. His family promised me that I would. Marriage was just a ticket to get there.

But you write that you were very hesitant to marry. Yet your parents encouraged it.

I do hold them accountable. When my eldest daughter turned 16, I would look at her and think, “Is there any reason I would make her marry a stranger 11 years her senior and move to Australia or somewhere?” The answer is no way in hell. So why did my mom think it was okay to do that?

Still, once you arrived in Canada, you tried hard to be a good wife.

I did. My mother-in-law would say, “You should be grateful you got to the purpose of being a woman sooner rather than later.” And so I tried. Am I supposed to be more submissive? Talk less? Cook better food? Wash clothes better? Keep the baby quieter at night? No matter what I did, I was never a good wife. I was the one who didn’t wear the right colour. I was the one who didn’t wear the hijab properly and my hair started to show. My mother-in-law said a good wife tolerates things for the sake of the family. This whole idea of honour kept coming back.

And once you were divorced?

I felt miserable. There were times I tried to crawl my way back to him. There were many confusing years. I was being approached by other men from my culture who now thought I was fair game. And these men acted as though they were doing me a favour by giving me their attention. Because they saw me as damaged; used.

That happens to many divorced women.

Sure, but when a white woman leaves an abusive marriage, she is often congratulated. Good for you! But when a brown woman leaves an abusive marriage, she’s often shamed.

It seems that your ex-husband could use a bit of psychological counselling. He’s under the thumb of his mother. Did you ever hope you could help him?

In order for anyone to help you, you have to want help. You have to admit that there’s something you need help about. And he doesn’t. In his mind and in his family’s mind, it’s the Canadian culture that corrupted me.

But there were good moments with him.

I wanted to make sure he comes across as human because abusers are rarely ever the caricatures as portrayed in movies and the media. They have good in them.

It’s interesting that you gained some freedom by convincing your mother-in-law that you could make money by running a small daycare in the house; that the two of you could go shopping if you got your driving licence and a car; that you needed a cellphone to communicate with the parents of the children you cared for.

It was totally calculated. I had figured out at that point that if I’m going to get anything done, I needed to have her on board.

Making money was essential to getting free.

Big time. There’s a scene in the book when I took my daughter to Tim Hortons to get a coffee and a doughnut. I didn’t have enough money. A stranger bought it for me. I was so humiliated. I was like a beggar. I gained confidence when I started making money.

Your book reveals aspects of traditional Muslim culture. Are you nervous about its publication?

I am. I will face the wrath of people who feel I’m defaming Islam. But this book is not about Islam. This book is about abuse against women. Sadly, abuse happens across cultures, across religions, across backgrounds. But religion is often used as a tool to justify abuse. And the positive feedback from when I tell my story far outweighs the negative – even in Pakistan.

Do you identify as Muslim still?

I don’t like answering that question.

Is that a no?

I consider myself a humanist.

How do you protect yourself from the backlash?

I am very selective about who my friends are and I am extremely selective about where I speak. About four or five years ago, I was saying yes to every speaking engagement. I was asked to speak at a Pakistani community event, and the organizer asked me to come in to give them a run through of my speech. I told him I would talk about how I was emotionally, psychologically, physically, financially and sexually abused in my marriage. And he said, “But he was your husband. How could he sexually abuse you? He had a right.” And I said, “Look, the day after my father died, my husband came to Pakistan where I was. I was five months pregnant. And instead of consoling me, the first thing he did was force me to have sex with him. If that’s not sexual abuse, what is?” He said, “I get it. You have become very progressive but you have to make sure you are sensitive to our culture as well. You cannot say those things on stage. Just take those bits out.”

And did you?

No. There were women in that community that needed to hear that. I saw a lot of women in the audience nodding and they had moist eyes, but they wouldn’t dare come up to me in front of their husbands.

Nothing deters you?

I will never stop this work. I found my why.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Expand your mind and build your reading list with the Books newsletter. Sign up today.