Picture books are more likely to star animals than people who aren't white – in 2016, the Cooperative Children's Book Center at the University of Wisconsin analyzed more than 3,000 books, and found only 22 per cent included at least one character of colour. That's only slightly better than it was 20 years ago, when the figure was nine per cent, and Junot Diaz wasn't yet a Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist. Back then, he was just a godfather with a talent for telling stories, one who promised his goddaughters that he'd write a book about kids like them.

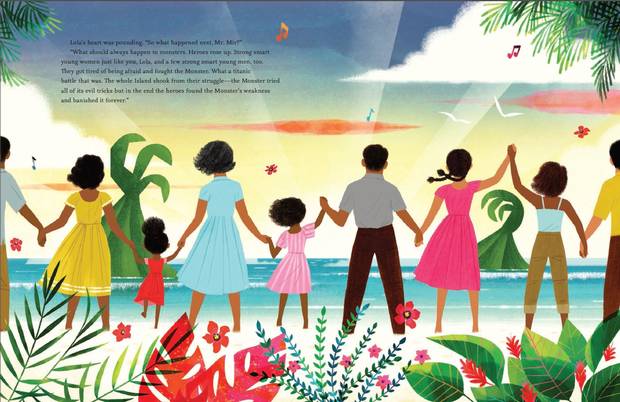

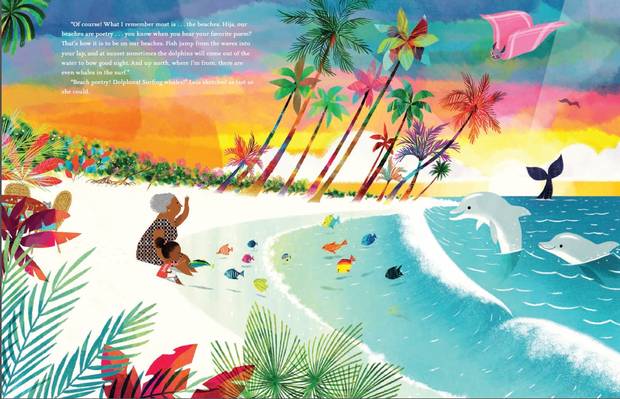

This month, he finally made good on his promise with the release of Islandborn, a gorgeous, tropical sunset of a book. In it, black and brown children will see families that look like theirs with lives that seem familiar, too. It's a story about leaving one home and building another, infused with all of the nostalgia and mystery that immigration demands.

Diaz, who was born in the Dominican Republic and teaches at the Massachusetts Insitute of Technology, spoke to the Globe's Denise Balkissoon about why representation matters and whether children should be shielded from sad or difficult stories.

My son is four and we've had to read him this book at least twice a day since we got it. He really, really loves the pictures. I was wondering how you got matched up with the illustrator, Leo Espinosa.

I was looking for an artist who could draw in that gorgeous retro style. This had everything to do with growing up as a kid and always seeing retro commercial illustration but never seeing people of African descent. So when I finished this kids book, my editor was like, "There's this man," and I said, "Well, he better be Caribbean," and she said, "He is Caribbean." As soon as I saw his art, I begged my ancestors that this guy was available. Because he had it, he had it, he had it.

I hear you really like the way he does everyone's hair.

You would think he spent his childhood growing up in an African diasporic salon. He grew up in Colombia, which is the same thing.

You wrote this book for your goddaughters, because they felt like their experiences were not reflected in the books they read as immigrant kids.

By the time they were 7 and 6, they were clamouring for representation. When you look at how few children's books are about people of colour, about children of colour, about communities of colour, that is just an extraordinary absence. It's just abusive.

"Abusive" is a pretty intense word.

I think that if I deny you all images of yourself and I starve you of any healthy representation, that's abuse. We could say that, "Yes, well it's the market that did that, it's all these other forces," but ultimately the reason that we don't have equity, the reason that we don't appear in stories, is because of histories of exclusion and oppression. To pretend that the fact that we're not in these books is just some innocent happenstance, some outcome of the market, is a lie.

My son just graduated from baby Lego to big kid Lego and I realized that Lego only makes yellow generic people. So specific characters, like NBA stars, are black or brown, but everyday people are yellow. They've argued that it's not white, it stands for every race.

Then why are the NBA players coded to stand for only one race? You know, it's just nonsense. There are people who think of these things as completely innocent, because they are not being victimized by it. Their children are not the ones growing up with their eyes being scalded by their own alienation.

I was thinking about all the times that I realized that books that I loved when I was younger were racist. The Secret Garden is one, realizing that the "darkies" in India are my ancestors. I assume you've had that kind of experience as well.

Of course. It's a common one, to discover that a text that you thought was your friend was in fact not. I think that we have to be able to hold the two experiences if we can. To understand that as a child, we didn't have any option other than to be friends with people who didn't like us. Now as adults, we can understand what it was, and we don't need to blame ourselves for being so in love with this person who didn't necessarily love us back.

The idea is not to pass on the same bad choices. To be able to serve as something of a navigator for a young person so that they don't fall into the same trap.

Is there a particular book that you remember, that one day you woke up and were like …

Oh God! Yes! So many! I still remember reading Watership Down and loving Watership Down, it's about these rabbits, how could it be anything else – and there is Richard Adams talking about how rabbits and their senses are attuned 'just like primitive peoples are.' And then of course Tolkien and his description of black men looking like half trolls, that wasn't fun. It wasn't fun reading Little House on the Prairie, you know…

That's definitely one of mine, Little House on the Prairie. I just loved those books and then it was like oh, they're actively stealing people's land.

Yeah, and that great line that they excised in later editions but when I was a kid was still there: "There were no people, only Indians."

There are a number of picture books out now that deal with what we might call "real issues" and some people resist because, you know, children are so young and so innocent. You've said that not every childhood is innocent.

No, not at all.

What do you mean by that?

Well, one of the great burdens that children have is innocence. They're doing the work, they're covering up their society's fiction of its own innocence.

You see this when you teach at university, how often young people have spent their lives believing these myths of innocence – believing that their country is innocent, believing that whatever their identity location is is innocent, believing in these mythologies of innocence. It's often a rude shock when they discover that they've been doing all this bogus work to keep a deception going.

The average child faces reality. They don't grow up inside of this coddled environment, they face reality every moment of their lives. To be young is not about innocence. It's about how vulnerable you are, how tremendously vulnerable you are.

I myself think that it's important to give children their due, to acknowledge their sophistication and their ability to hold complex, painful truths in ways that don't leave them damaged or despondent or scared. Young people are incredibly smart. They can tell that there's a story behind the story.

Islandborn is about a little girl named Lola who is from an unnamed island and she has to draw a picture about it for school. She's asking everyone their memories and finally the last person tells her about this monster that terrorized the island for 30 years. Is the monster specifically Rafael Trujillo, the 20th-century dictator in the Dominican Republic, where you're from?

No, I didn't think of a specific person. I thought of it as a stand-in for political monstrosity, as a counterpoint to the very unsatisfying nonsense that immigrant and refugee children are sometimes fed: which is that we come to places like Canada, we come to places like the United States because we lack x, y and z in our country. A slightly more accurate story is that many of us who find ourselves in places like the United States and Canada come because there are political monstrosities at home.

Like Lola says, “Oh it’s so musical and all the food is so delicious, why did we even leave?”

Yeah, she's got a child's genius, a child's wisdom. Everyone is sort of selling her the sort of traditional children's book celebration model, you know, but something doesn't square. There's something missing in the story and in some ways, that's her quest.

This interview has been condensed and edited.

Junot Diaz will be in conversation with Denise Balkissoon on March 24, 6 p.m., at 918 Bathurst St., Toronto. For tickets, visit Type Books at 883 Queen St. W., typebooks.ca.

Questions from a four-year-old

My son Lennox, age 4, also has questions for Junot Diaz about Islandborn.

Why does Lola not remember the island?

Cause she came over too young, she was like, 1. She was just a little one. You know it's hard to remember when you're 1, unless you're like a wizard, you're not going to remember it. She came over too, too little.

Why does the mango make you cry?

The reason the mango makes Mr. Rodriguez cry is because he misses the mangos from the island. The mangos in the city are not the same, they don't taste as sweet, so he's thinking about them and he sheds a tear because he wishes they were with him.

Why do they say "abuela" instead of "grandma"?

Because this is a family that speaks in Spanish and so some words, no matter what, you say in Spanish. I always think those are the words of love and so "abuela" is a word of love. So it stays, no matter what language they're speaking.