The mystery is absolutely tantalizing. The National Gallery of Canada (NGC) is about to pay somewhere in the neighbourhood of $10-million for a single work of art it deems so important to Canadians that it is selling off a major painting by Marc Chagall to pay for the thing. What thing? Well, that’s what art lovers and taxpayers will all want to know. The mere price tag will have them salivating or fulminating, depending on their stripe. But right now, the gallery must remain mum to protect the deal.

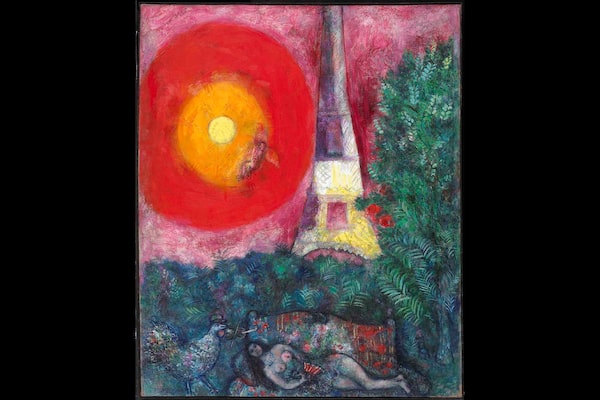

The plan came to light when Chagall’s La Tour Eiffel showed up in a Christie’s auction catalogue. The brightly coloured, 1929 painting of the Paris landmark will be sold on May 15 in New York and is expected to raise at least $8-million to $11-million.

Marc Chagall, The Eiffel Tower, 1929: Oil on canvas, 100 x 81.8 cm.National Gallery of Canada

Reputable public museums are not allowed to sell art to pay debts, renovate buildings or just keep the lights on: Several smaller U.S. museums have got into hot water in recent years when they have been desperate enough to try. Deaccessioning, as it’s called, is permitted only to cull a collection of things that no longer fit and the proceeds must go to buy more art. That is what NGC is doing, arguing that it has plenty of Chagalls – it is also selling a few pieces of ancient art, an area in which it doesn’t collect – and that it needs to raise the money quickly to buy a significant art work that would otherwise be taken abroad.

Canada, as with many other Western countries, has laws that force collectors who want to sell major pieces of cultural heritage to look for buyers inside the country before they will be given an export permit. Usually, major public institutions are approached and they go looking for philanthropists to help. Apparently in this case, no sugar daddy could be found.

So what might this art work be and why is it so significant to Canadians? Prices for 20th-century Canadian masters have been rising rapidly in recent years as the Group of Seven – and Lawren Harris in particular – have started to come to international attention. Nonetheless, if it’s a Canadian work that is going to cost $10-million, it’s either a whopping big Group of Seven or possibly a whopping big painting by Jean-Paul Riopelle, the Quebec abstract artist whose work has always sold well on the international market. Harris’s Mountain Forms of 1926 set a record for Canadian art at auction in 2016, when it sold for $9.5-million – plus an 18-per-cent buyer’s premium for a total of $11-million. Riopelle’s Vent du nord of 1952-53 was sold for a total of $7.4-million last year.

But it is also quite possible the gallery has decided that a work by a foreign artist is worth fighting to keep in Canada. Cultural significance does not necessarily mean national significance: In the United Kingdom, which has a particularly strict system of controls, export permits are regularly denied to works created by artists of the Italian Renaissance.

In January, the Canadian Cultural Property Export Review Board slapped delays on bronze sculptures by the British artist Barbara Hepworth and the German artist Max Ernst, plus a Picasso drawing that sellers were seeking to export. None of these seem significant enough to merit the NGC’s hasty fundraising. That might seem more fitting for a work such as Jackson Pollock’s Cut Out Figure, from 1948, a seminal piece in which the famed U.S. abstractionist reintroduced the figure to his painting − and a work that was at one time hanging in the Ottawa gallery, where it was on loan from a private Canadian collection.

Will Canada soon be debating whether Pollock, or some other international art star, trumps Chagall? We’ll have to wait until at least the summer before the dust settles on the Chagall sale and a new purchase may be revealed.

Kate Taylor

Kate Taylor